Venezuela’s Oil Reset Isn’t an Oil Story—It’s a Contract Story

When a government invites private capital into a distressed petro-state, the headline is always the same: barrels, reserves, and the promise of cheaper energy. But the real variable—the one markets quietly price before rigs ever arrive—is credibility.

That’s why the White House meeting with major oil executives, framed around securing as much as $100 billion in private investment to rebuild Venezuela’s neglected energy infrastructure, matters far beyond oil. It’s a live experiment in whether political guarantees can substitute for missing institutions, and whether investors believe those guarantees will survive the first legal dispute, the first election cycle, or the first change in diplomatic temperature.

A policy pitch disguised as an energy deal

The administration’s message to executives was blunt: invest, and you will be protected. The President publicly promised “total safety,” emphasizing that companies would deal directly with the U.S. rather than navigating Venezuela’s historical maze of asset seizures, sanctions risk, and regulatory uncertainty. The ask—up to $100B of private capital—was paired with the idea that what the companies need is not subsidies, but “government protection.”

At first glance, this is a classic ‘post-crisis reconstruction’ pitch. Yet it differs in one important way: it is trying to rebuild an investment environment without first rebuilding a full domestic rule-of-law framework. In other words, it’s attempting to import trust—to wrap a high-risk operating environment in an external security umbrella that makes capital feel safe enough to move.

Why that matters: in oil, geology is rarely the bottleneck. Contracts are. Venezuela’s reserves may be expansive, but the investability question is whether cash flows can be owned, repatriated, and defended—through courts, arbitration, and stable regulations—when the trade winds shift.

“Un-investable” is not an insult—it’s an accounting category

ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods captured the core issue in a single sentence: under today’s frameworks, Venezuela is “un-investable.” That word is doing more work than it seems. It is not a moral judgment; it’s a risk classification. ‘Un-investable’ means the expected return cannot compensate for the combined probability of expropriation, contract revision, payment friction, and reputational/legal exposure.

From an institutional investor’s perspective, Venezuela’s problem is not that it lacks opportunity—it’s that it lacks predictability. And predictability is what converts an oil reservoir into a financeable asset. Without it, the discount rate explodes, insurance costs soar, and boards are forced into a defensive posture: send assessment teams, delay commitments, and demand structures that keep optionality high.

In practice, “investability” is a stack, and every layer must hold:

• Title and operating rights: who owns what, and can that ownership be defended?

• Cash-flow rights: can revenues be collected reliably, in hard currency, and repatriated?

• Dispute resolution: will arbitration awards be honored—and by whom?

• Regulatory durability: will hydrocarbon laws and tax regimes remain stable long enough to amortize multi-year capex?

• Sanctions and compliance: can the entire system operate without legal whiplash for banks, insurers, shippers, and counterparties?

What “total safety” really means: the U.S. becomes the hidden counterparty

When political leaders promise safety for private investments in a volatile environment, they are effectively offering a form of political-risk insurance—sometimes explicit, often implied. The important nuance is that this shifts the identity of the counterparty.

Instead of trusting Venezuelan institutions, firms are being asked to trust U.S. enforcement capacity: sanctions policy, security coordination, and the ability to stabilize commercial arrangements. If that’s the model, the ‘deal’ is not simply between Exxon, Chevron, or service companies and Venezuela. It becomes a triangular arrangement where the U.S. acts as a guarantor, referee, and sometimes even as the operational gatekeeper.

This structure can unlock capital—because it reduces tail risk. But it also introduces new questions:

• Where does the guarantee end? Protection language can be broad in speeches and narrow in contracts.

• How is risk priced? If the U.S. is implicitly underwriting stability, investors may accept thinner margins—until a dispute reveals the fine print.

• What incentives get created? A safety net can encourage faster investment, but it can also encourage aggressive behavior and moral hazard if participants believe losses will be politically socialized.

$100 billion: a number that signals ambition—and reveals the timeline problem

Large round numbers serve a political purpose: they communicate seriousness. Yet in energy, scale is inseparable from time. A key detail from the meeting was the suggestion that it could take 8 to 12 years for Venezuela’s daily production to triple toward 3 million barrels per day. That is not a criticism; it is realism. Oil capacity is rebuilt by logistics, workforce, power infrastructure, and maintenance—slowly, and with compounding constraints.

To understand why, think of Venezuela’s oil system less like a single ‘field’ and more like a chain of fragile links. Capital must fix multiple bottlenecks at once, or the system fails to deliver headline output even if upstream wells improve. The practical capex map usually includes:

• Upstream rehab: workovers, spare parts, drilling services, and reservoir management.

• Midstream reliability: pipelines, pumping stations, storage, and security of transport routes.

• Power and utilities: oil production is an industrial process that depends on stable electricity and water handling.

• Refining/export capacity: even if crude flows, export logistics and compliance-ready shipping determine realizable revenue.

• Human capital: retaining and re-training skilled labor after years of underinvestment is not instant.

So the more honest framing is: $100B is not a ‘flip-the-switch’ number. It’s a multi-year reconstruction budget—and reconstruction is only financeable if contracts remain intact long enough to pay it back.

The real market signal: caution from people paid to take risk

Oil executives are not known for risk aversion. They routinely operate in politically complex regions. When leaders of that industry still hesitate—citing seizures, legal instability, and the need for durable investment protections—it’s a meaningful signal. It suggests the opportunity is obvious, but the rule set is not.

This is also where policy narratives collide with corporate memory. Venezuela has a documented history of state intervention and asset disputes. For boards and shareholders, “we were burned before” is not rhetoric; it’s a compliance file, a litigation archive, and a set of internal lessons that govern decision-making today.

In that sense, the meeting is less about persuading companies that Venezuela has oil. Everyone already knows that. It’s about persuading them that the next decade will not resemble the last decade, and that protections will be enforceable even when it becomes inconvenient to enforce them.

Why this matters even if you don’t trade oil

Energy reconstruction deals are often treated as sector-specific. They’re not. They shape three broader macro channels: inflation expectations (via fuel costs), geopolitics (via resource control), and capital allocation (via who gets privileged access and policy protection).

If the U.S. can credibly stabilize Venezuelan output over time, it potentially adds medium-term supply elasticity to the global system. That doesn’t automatically mean lower prices tomorrow, but it can change how markets price future scarcity risk. Conversely, if the project becomes tangled in legal disputes or political backlash, it can do the opposite: increase the ‘geopolitical risk premium’ embedded in energy markets.

There is also an institutional precedent here. The pitch implies a model where governments move from sanctioning and isolating to actively coordinating commercial reconstruction—blurring the line between foreign policy and industrial policy. That shift, if repeated elsewhere, changes how investors think about political alignment as a financial variable.

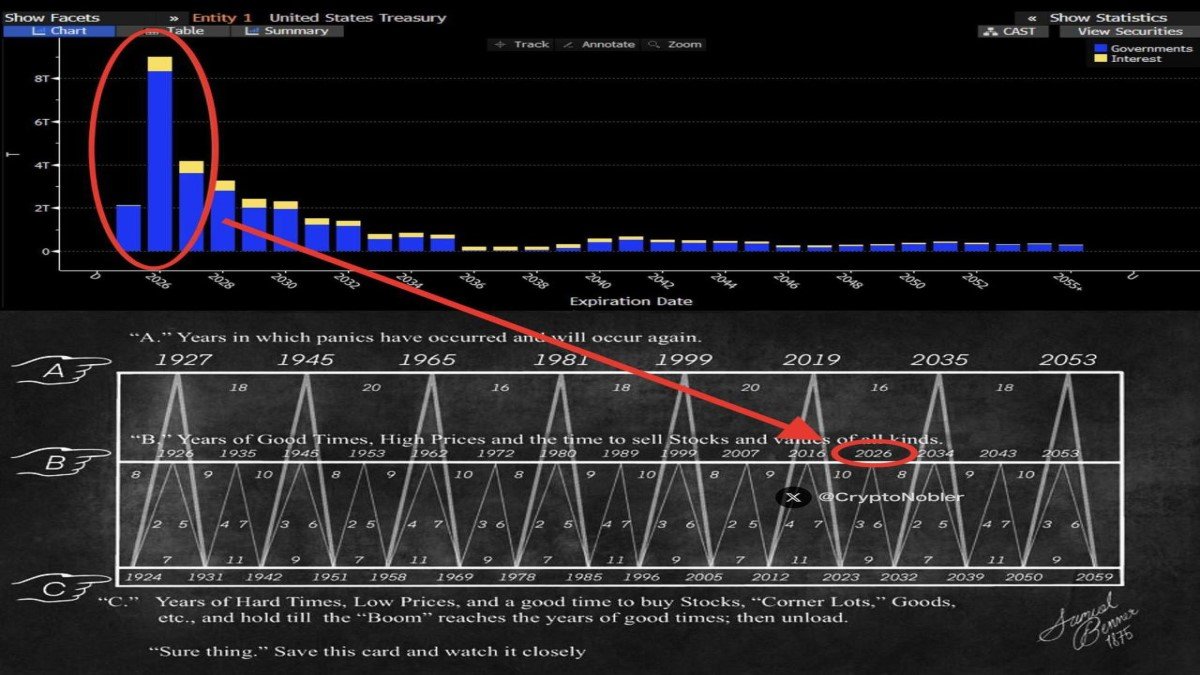

Three scenarios to watch in 2026–2028

Rather than forecasting a single outcome, it’s more useful to map scenarios—because the key driver is not oil price, but legal and political execution. Here are three plausible pathways, each with distinct market consequences.

1) Rapid normalization: Venezuela’s commercial frameworks are rewritten quickly, protections strengthen, and companies commit staged capex with clear arbitration and repatriation mechanisms. Output rises gradually; risk premium compresses.

2) Managed ambiguity: Assessment teams arrive, limited projects begin, but deeper legal reforms lag. Capital flows in cautiously through short-horizon contracts. Output improves, but below the political narrative. Volatility stays elevated.

3) Legal whiplash: disputes over seizures, sanctions interpretation, or governance legitimacy trigger lawsuits and compliance pullbacks. Capital pauses, and the story becomes a warning label for emerging-market energy exposure.

The difference between these scenarios will be visible in non-headline indicators: contract language, escrow structures, arbitration venues, the behavior of insurers and shippers, and whether executives keep describing the country as “un-investable” or start describing it as “structured but workable.”

Conclusion

The White House can invite capital, promise safety, and frame Venezuela as an economic opportunity. But markets will ultimately treat this as a credibility referendum. Oil is the asset; enforceable rules are the product.

If the administration wants $100B of private money to move, it must do more than persuade executives in a meeting. It must build a contract ecosystem that can survive the first shock. Until then, the smartest way to read the story is not as a rush for barrels—but as a high-stakes test of whether political guarantees can temporarily stand in for institutions, and what it costs when they try.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why did oil executives hesitate if the opportunity is large?

Because oil projects are long-duration investments. If legal protections, cash-flow rights, or sanctions rules can change abruptly, the risk becomes difficult to price—and boards will demand stronger safeguards before committing capital.

What does “un-investable” mean in practical terms?

It typically means the expected return cannot reliably compensate for political and legal tail risks—such as expropriation, contract changes, payment restrictions, or regulatory instability—over the time needed to recover investment.

Does $100B imply quick production growth?

Not necessarily. Large investment can rebuild capacity, but timelines are constrained by infrastructure, skilled labor, utilities, and logistics. Even optimistic pathways often unfold over many years.

Why is this relevant to broader markets?

Because energy supply expectations influence inflation narratives, geopolitics influences risk premiums, and the policy model—government-backed commercial reconstruction—can reshape how investors price political alignment.

What should observers watch next?

Look for concrete commercial frameworks: durable hydrocarbon laws, credible investment protections, arbitration mechanisms, sanctions/compliance clarity, and whether insurers and logistics providers treat the flow as stable enough to support scale.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or investment advice. Markets involve risk, and outcomes may change rapidly as new information emerges.