U.S.–Venezuela: From Heavy Oil to Global Geopolitics—and Why Markets Can Rally Even When Headlines Look Explosive

To analyze the U.S.–Venezuela situation, it helps to set one rule up front: this is not a debate about moral legitimacy or legal justification. Financial markets rarely trade “right vs. wrong.” They trade constraints, incentives, and second-order effects. That framing matters because Venezuela is not just a country in the news—it’s a bundle of strategic constraints wrapped around heavy oil, decayed infrastructure, and great-power competition.

In that sense, the storyline has already escaped the oil-only box. It now touches energy security, defense budgets, U.S.–China relations, and the uncomfortable question of “precedent” in a world that increasingly talks in spheres of influence. The most interesting part is not the headline itself. It’s how many different markets—equities, commodities, crypto—are trying to price the same event through completely different lenses.

The core commodity isn’t “oil.” It’s the right kind of oil.

Venezuela’s competitive advantage is not simply that it has a lot of barrels. The key is the type: much of the country’s resource base is heavy crude—thicker, more complex, and generally more expensive to produce and refine than light crude. Heavy barrels behave like a specialized input. When they disappear from global circulation (or become politically risky), refineries designed for heavy crude don’t magically become efficient overnight. They either run sub-optimally or pay up for substitutes.

This is why the U.S. Gulf Coast matters. Many refineries in that region were built or upgraded to process heavy crude efficiently. If Venezuelan heavy returns at scale—through reopened flows, eased sanctions, or simply fewer disruptions—the story is not “more oil.” The story is better feedstock matching. That can ripple into margins for refined products like diesel, jet fuel, and asphalt, because refinery economics are often defined by what you can process cheaply and what you can sell at a premium.

Michael Burry’s “Valero thesis” is a refinery design thesis, not a political thesis

Reports circulating today say Michael Burry (well known from The Big Short) has held Valero Energy since 2020 and has grown more confident as U.S. involvement in Venezuelan oil restoration looks more plausible. Whether one agrees with Burry or not, the interesting part is the logic: some Gulf Coast refineries were built to handle Venezuelan heavy crude, but for years had to rely on less-optimal inputs, which can compress profitability.

If heavy Venezuelan barrels re-enter the mix in a stable way, refining can become less like improvisation and more like engineering again. That can improve the economics of turning crude into specific products—especially in segments where demand is sticky (aviation fuel, industrial diesel, construction-linked asphalt). The market’s positive reaction to certain refining names can be read as investors re-pricing the feedstock advantage rather than making a grand statement about geopolitics.

The “rebuild trade”: why oilfield services may be the quiet winners

Even if the politics stabilize, Venezuela’s oil sector doesn’t restart like a light switch. Years of underinvestment and sanctions pressure typically leave a system with broken pipelines, aging equipment, bottlenecked logistics, and depleted technical capacity. In this kind of reset, the value capture often shifts downstream into the companies that can restore functionality—wells, pumps, pipelines, processing, safety systems, maintenance cycles, and operational discipline.

That’s why U.S. oilfield services names are frequently discussed in this context. Firms such as Halliburton, Schlumberger, and Baker Hughes (as examples of the category) have the expertise to rebuild the “boring” parts of the system that actually determine output: service contracts, equipment deployment, and integrated project execution. If Venezuela becomes a multi-year restoration project, services can benefit not from a single price spike, but from a long-duration investment cycle.

Defense and infrastructure: the uncomfortable symmetry of geopolitical stress

Geopolitical stress tends to widen the funnel of potential beneficiaries. If U.S. engagement deepens—through security presence, logistics, intelligence, or stabilization support—defense spending often rises at the margin. That can translate into stronger medium-term demand for defense technologies, surveillance, logistics, and procurement supply chains. It’s not “good news.” It’s a structural reallocation that markets are trained to anticipate.

Infrastructure is the other side of the same coin. Rebuilding energy systems typically requires ports, roads, industrial equipment, engineering services, and a serious logistics backbone. In periods like this, capital expenditure becomes narrative-proof: it can happen under many political scripts because the physical system needs repairs regardless of ideology. For investors, that creates an uncomfortable clarity—the bill will be paid, and someone will earn the revenue.

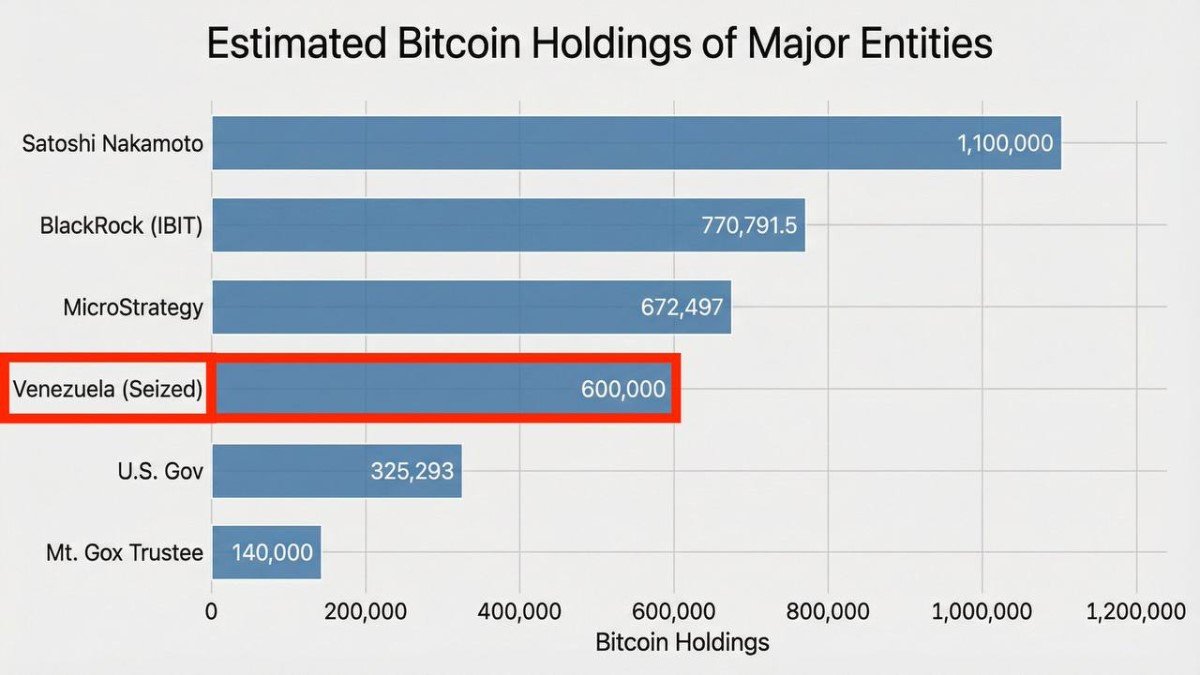

China’s problem is not just lost barrels—it’s lost optionality

On the other side, the immediate market signal has been pressure on Chinese oil names. You noted that major Chinese energy stocks in Hong Kong sold off, with moves like CNOOC down roughly ~3% and PetroChina down ~5% amid concerns that China’s access to Venezuelan crude could tighten after Maduro’s removal. The cited concern—Venezuelan crude representing roughly 5–8% of China’s oil imports—matters less for the percentage and more for the refinery fit.

China has invested heavily in refining capacity and crude-processing configurations over many years. When a refiner is tuned for certain grades, losing that supply is not like losing a generic ingredient; it can force costly substitutions, compress margins, or reduce utilization. More subtly, the loss is strategic: if the U.S. influences the flow of a specialized heavy-crude supplier, China loses optionality—the ability to diversify supply without paying a geopolitical premium elsewhere. Markets tend to punish that loss of optionality quickly, even before any physical disruption is confirmed.

Why Taiwan and Greenland suddenly enter the conversation

This is where the narrative jumps from energy to geopolitics. Once an event is framed as a strong action in a “backyard,” it invites comparisons—fair or unfair—to other contested zones. That’s why Taiwan is brought up: observers worry about precedent, about who gets to enforce what, and what arguments might be reused in different theaters. Even if the situations are not symmetrical, markets are allergic to precedent because precedent changes the perceived rulebook.

Greenland appearing in the discussion is another sign of “rulebook anxiety.” Most experts still view a Venezuela-style action elsewhere as highly unlikely, but the fact that it is discussed at all signals something important: ideas that used to be dismissed as unthinkable are now treated as conversationally possible. That alone can affect risk premia, alliance trust, and how quickly markets move from complacency to hedging.

So why did markets look broadly positive?

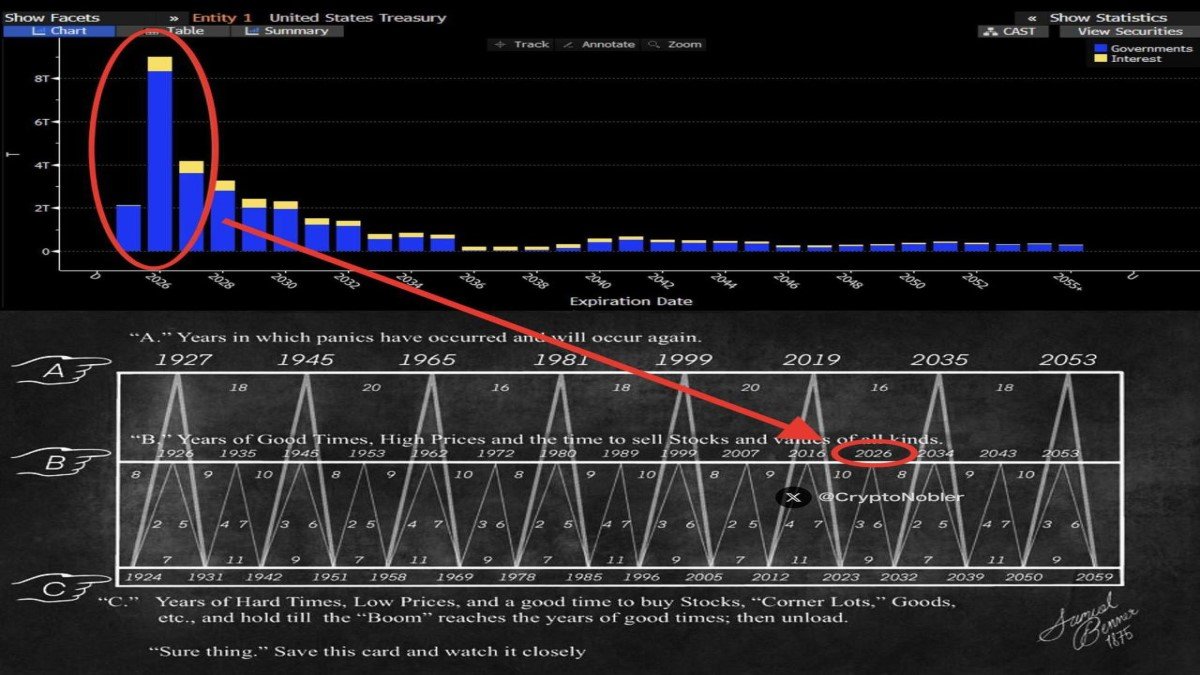

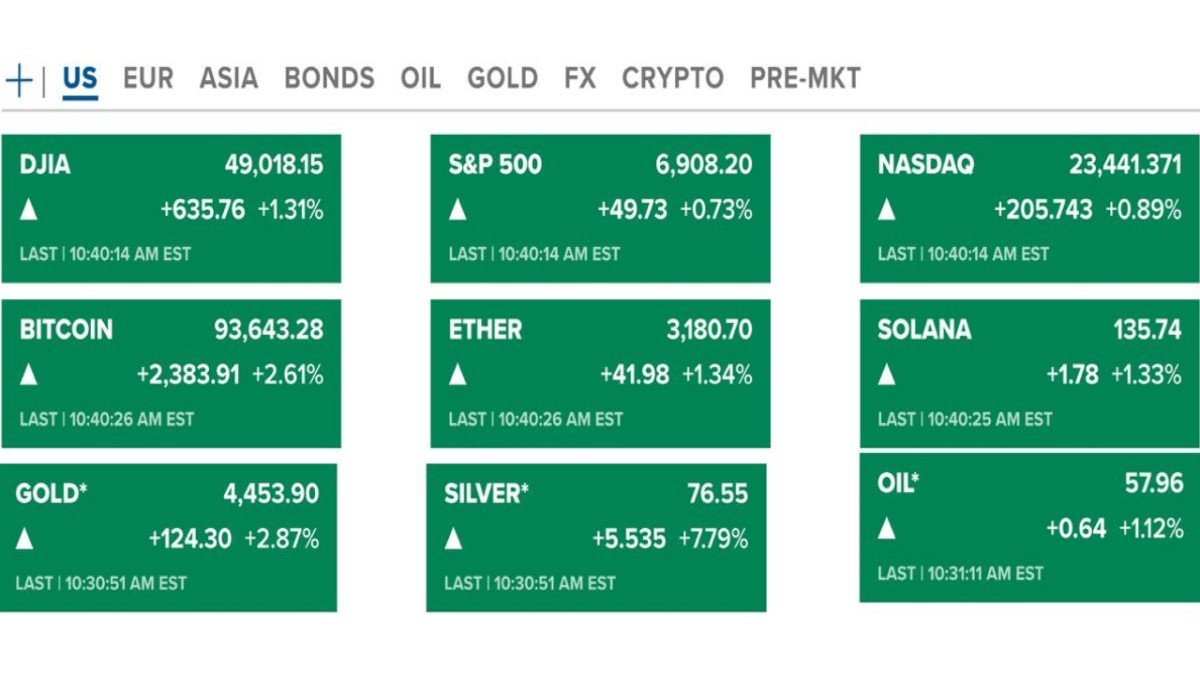

You highlighted an unusually synchronized session: stocks, crypto, gold, silver, and even oil moving higher together. That can look contradictory until you separate the forces at work. In the immediate aftermath of a shock, markets can rally for reasons that have nothing to do with optimism. Sometimes they rally because participants are buying hedges (gold, BTC), rotating into perceived winners (energy/defense), and simultaneously assuming that a future policy path could increase supply or reduce uncertainty later (which can stabilize broader equities).

Another interpretation is “wait-and-see pricing.” If investors believe the short-term oil outcome is unclear—production could rise later, but risk premia could rise now—they may refuse to price a single dominant scenario. In that regime, you can get a broad green tape: risk assets lift on positioning and relief that worst-case disruptions are not yet visible, while hard assets lift as insurance against longer-run geopolitical fragmentation.

The deeper takeaway: this is a regime story, not a headline story

The market is quietly asking a bigger question: are we moving into a world where energy and security are re-nationalized priorities again? If yes, then capital flows change behavior. Supply chains get shorter. Defense budgets get stickier. Energy infrastructure becomes strategic rather than purely commercial. And “cheap global optimization” becomes less reliable as a default assumption.

In that world, Bitcoin and crypto can experience a paradox. In the short run, geopolitical shocks can reduce liquidity and trigger risk-off selling. But over longer horizons, fragmentation and currency-bloc dynamics can increase demand for assets that are portable, liquid, and globally recognized. That doesn’t mean “BTC always wins.” It means the reason people hold BTC may shift—from speculative upside toward strategic optionality.

Conclusion

The U.S.–Venezuela situation is no longer an “oil headline.” It’s a layered value-chain story (heavy crude and refinery design), a corporate earnings story (refiners and oilfield services), and a geopolitical story (U.S.–China leverage, precedent anxiety, and sphere-of-influence narratives spilling into Taiwan and even Greenland conversations). The market’s broadly positive reaction is not proof that risks are gone—it’s evidence that investors are still negotiating which regime they’re entering.

In the coming weeks, the most informative signals won’t be the loudest tweets. They’ll be the quiet ones: refinery margin trends, services contract guidance, Chinese energy import substitutions, defense procurement commentary, and whether cross-asset correlations stay “one-way” or start to fracture. That’s where the market will reveal what it truly believes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does “heavy oil” matter so much?

Because many refineries are optimized for certain crude grades. Heavy crude can be a structural input advantage for complex refineries, affecting margins for diesel, jet fuel, and other products.

Does a broad market rally mean geopolitical risk is over?

Not necessarily. A rally can reflect positioning, relief, hedging, or a wait-and-see stance. Markets can move up even when uncertainty rises, especially if investors rotate into perceived beneficiaries.

Why did Chinese oil stocks react negatively?

Because the concern is not just volume but suitability and optionality. Losing access to a compatible crude grade can compress margins and reduce supply flexibility, which markets re-price quickly.

Is Bitcoin a safe haven in geopolitical stress?

Sometimes it behaves like a risk asset in the short run (liquidity-driven). Over longer horizons, some investors treat it as strategic optionality—but it remains volatile and context-dependent.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. Markets involve risk and uncertainty. Any references to individuals or reported positions are presented as commentary on market narratives, not as endorsements or recommendations.