The 10% Credit Card APR Cap Debate: Consumer Protection, Credit Rationing, and the Hidden Cost of “Affordable” Money

When a politician says Americans are being “picked clean” by 20%–30% credit card interest rates, the claim lands emotionally because it’s not abstract. Most households don’t experience monetary policy through bond yields or yield curves. They experience it through monthly statements: minimum payments that barely touch principal, balances that refuse to shrink, and an interest meter that feels punitive rather than financial.

So the proposal—cap credit card APR at 10% for a year, starting January 20, 2026—sounds like the rare policy that is both simple and humane. But then a financier like Bill Ackman pushes back: cap rates too low and lenders will stop lending, especially to riskier borrowers. Suddenly the debate looks less like “good vs evil” and more like a friction point between two truths that can coexist: high interest hurts, and unsecured credit is priced high because losses are real.

The core issue is not whether 20%–30% APR is uncomfortable. It’s whether a society wants to solve that discomfort by changing the price of credit, or by changing the structure of household finances that makes expensive credit necessary in the first place.

Why Credit Card APR Feels Like Gouging

Credit cards occupy a unique psychological space. They are marketed as convenience and rewards, but function as emergency liquidity for many households. When the same instrument that buys groceries also becomes a debt trap, interest feels less like a contract and more like punishment.

Two design choices amplify this perception. First, credit cards are revolving: there is no fixed end date, so debt can persist indefinitely. Second, minimum payments are engineered to keep accounts current while maximizing duration. That means the time cost of high APR becomes as important as the percentage itself. At 25% APR, a balance can turn into a lifestyle tax—paid not once, but repeatedly.

From Trump’s perspective, a 10% cap is a moral reset button: stop the bleeding, give families breathing room, and force issuers to behave. This is a coherent political argument because it speaks to affordability, not finance theory.

Ackman’s Warning Is Not Just Corporate Self-Interest

Ackman’s critique is often dismissed as “Wall Street defending profits,” but the mechanism he points to is real: when you cap the price of risk, lenders ration credit instead. This is not ideology; it’s how markets behave when a price ceiling is below the level needed to cover expected losses and operating costs.

Unsecured lending is not like a mortgage. There is no house to repossess. The only collateral is the borrower’s future cash flow—and the lender’s ability to collect. When defaults rise, losses are direct. If an issuer can’t charge higher APR to riskier borrowers, it has two options:

• Reduce exposure (lower credit limits, close accounts, tighten approvals).

• Recover profitability elsewhere (higher annual fees, lower rewards, more penalty fees, stricter terms).

In practice, the first option hits vulnerable households hardest. Prime borrowers may still get access at 10% because their expected default risk is low. But the borrowers who currently pay 25% are precisely the borrowers who are most likely to be denied when pricing flexibility disappears.

So Ackman’s argument is not that high APR is good. It’s that a low cap can turn credit from “expensive and available” into “cheaper but unavailable.” That tradeoff is not hypothetical—many historical rate caps have produced some version of it.

The Tradeoff: Affordability vs Access Is Not Symmetric

Here’s where the debate gets subtle. A cap produces winners and losers, but not evenly.

Potential winners: borrowers who already have access and pay high rates despite being relatively stable (for example, households with thin credit files, or those who carry balances occasionally). If their cards remain open, a lower APR directly reduces their interest burden.

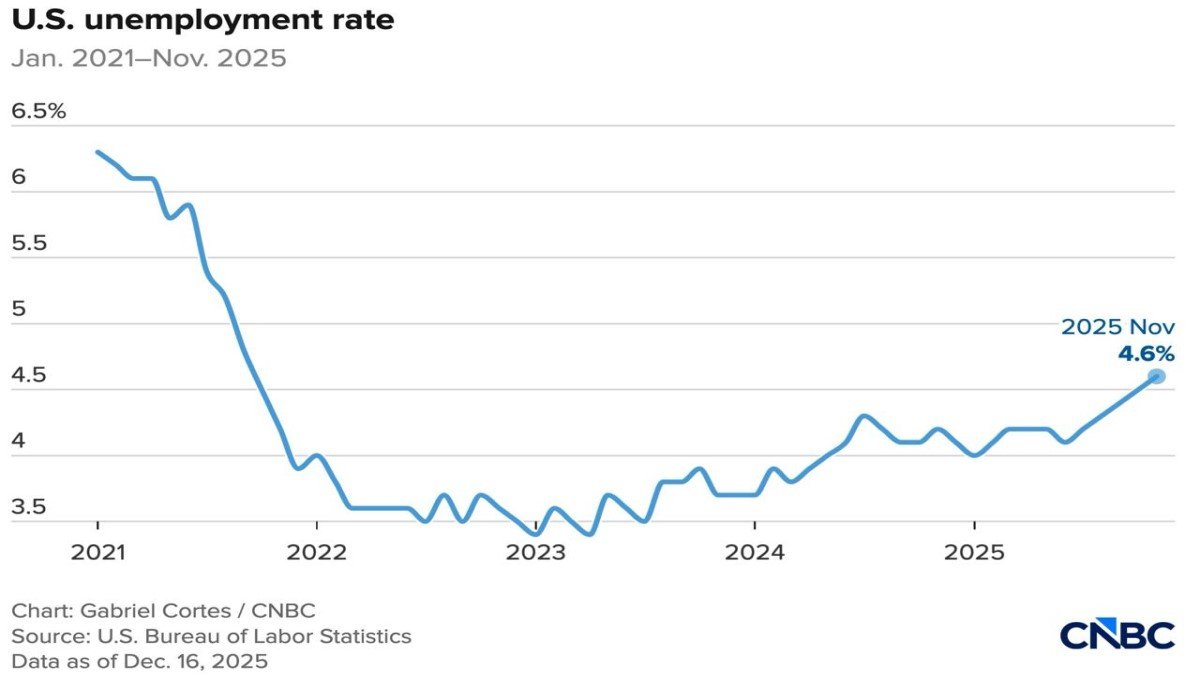

Potential losers: borrowers whose access is marginal—subprime, volatile income, prior delinquencies, or simply limited documentation. If issuers react by tightening credit, these households may lose not only cheap credit, but any credit. The cap can effectively push them out of the formal credit market.

And when people still need liquidity—because emergencies still happen—they don’t stop borrowing. They borrow elsewhere: overdrafts, payday lending, informal loans, “buy now pay later” structures with fees, or even late-payment cascades across utilities and rent. The policy may reduce one kind of pain while increasing another.

What Happens Inside the Credit Card Business Model

To judge a cap fairly, you need to understand what credit cards actually monetize. Issuers don’t earn only from interest. They earn from interchange (merchant fees), annual fees, late fees, and—critically—interest from revolvers who carry balances.

A cap compresses the interest component, which changes strategy. Three second-order effects often follow:

1) Risk shifts to non-interest fees. If issuers can’t price risk through APR, they may price it through fees. That can be worse for consumers because fees are immediate, less transparent, and often hit people at the moment they’re already stressed.

2) Rewards get devalued. Rewards are not free; they are funded by interchange and interest. Lower interest margins can mean lower rewards, making credit cards less attractive to low-risk users—the very segment issuers want to keep.

3) Underwriting becomes stricter and more data-hungry. When pricing flexibility is constrained, issuers become more selective. They may demand stronger credit histories or more verifiable income. This can worsen financial inclusion even if the policy was designed to protect households.

In other words, a cap doesn’t just lower APR. It forces the entire ecosystem to re-optimize—and that re-optimization may not favor the people policymakers intend to help.

Why a “One-Year Cap” Sounds Safe — But Can Still Distort

The proposal’s temporary nature is meant to soften concerns: a one-year cap provides relief without permanently rewriting credit markets. But temporary interventions can still cause lasting damage because credit markets are built on expectations.

If issuers believe pricing will be politically constrained again, they may respond conservatively for longer than the cap lasts. Credit decisions are not made one month at a time; they are portfolio decisions. A temporary cap can produce a semi-permanent tightening if it changes risk perception.

It can also create behavioral effects. If borrowers expect “cheap credit for a year,” some may borrow more, increasing future delinquency risk just as the cap expires. That could set up a political loop: rising defaults after the cap lead to calls for renewed controls, making long-term planning harder for issuers and consumers alike. This is how well-intended price controls can become sticky.

The Real Solution Is Not a Number. It’s a Design.

There is a deeper question beneath the headline: why do households rely on 20%–30% revolving credit to begin with?

In many cases, it’s because the financial system offers a strange menu: cheap credit for those who need it least (prime borrowers with assets), and expensive credit for those who need it most (people with income volatility). A cap tries to fix that by forcing cheapness onto the expensive segment. But if you don’t change the underlying risk, you don’t eliminate the cost—you relocate it.

A more structural approach would aim to reduce the need for high-cost revolving debt rather than merely lowering its price. Examples of design-level ideas (not prescriptions) include:

• Safer emergency liquidity (small-dollar credit products with clearer amortization, or employer-linked advances with guardrails).

• Stronger affordability tools (automatic payment plans, principal-first options, or friction to prevent indefinite revolving).

• Targeted consumer protections that reduce exploitative fee structures, not just APR.

These approaches are harder to sell politically because they don’t fit on a bumper sticker. “Cap APR at 10%” does. But policy that is easy to communicate is not always the same as policy that is easy to sustain.

So Who Is Right?

Trump is right that credit card APR at 20%–30% can be a crushing burden and can function like a regressive tax on households living close to the edge. If your income is tight, interest is not “the cost of borrowing”—it’s the cost of being unlucky at the wrong time.

Ackman is right that unsecured credit cannot be forced into cheapness without consequences. If pricing risk is prohibited, access becomes the adjustment valve. The most common victims of that adjustment are the very borrowers a cap is meant to protect.

What makes this debate difficult is that both positions are internally consistent. The conflict is not moral; it is mechanical. The cap is a lever. Pull it hard enough and something moves—but it may not be the thing you wanted to move.

Frequently Asked Questions

Would a 10% APR cap reduce household debt?

It could reduce interest costs for borrowers who keep access to credit and carry balances. But if access tightens, some households may shift to other, potentially more expensive forms of borrowing or fall behind on other obligations. Debt outcomes depend on how issuers and consumers respond.

Who would benefit the most from a cap?

Most likely borrowers who currently have high APRs but are still considered acceptable risks by issuers. If issuers tighten underwriting, marginal borrowers could lose access entirely and benefit less than expected.

Why can’t issuers just accept lower profits?

In competitive markets, issuers can’t sustainably lend at a loss without changing their model. If expected defaults plus operating costs exceed the capped return, they either restrict lending or shift revenue to fees and other charges.

Is there a middle ground?

Potentially. Policymakers can pair consumer protection with mechanisms that preserve access—such as targeted support for safer small-dollar credit, limits on abusive fee structures, or clearer amortization options that help balances decline rather than revolve indefinitely.

Conclusion

The 10% APR cap debate is a mirror. It reflects two versions of fairness: fairness as affordability (people shouldn’t pay 30% to survive), and fairness as access (people shouldn’t be shut out of credit because they’re risky). A price cap prioritizes the first. Markets respond by testing the second.

If the goal is to protect households, the strongest policy is rarely the one that sounds toughest. It’s the one that acknowledges the mechanism: when you cap the price of risk, you must decide who absorbs the risk instead—lenders, taxpayers, merchants, or borrowers through other channels. Until that absorption is designed intentionally, a cap may feel like relief while quietly becoming exclusion.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or investment advice. Policy proposals can change, and individual financial decisions should be made with professional guidance where appropriate.