When 300,000 Student Borrowers Hear “No”: Why Income-Driven Plan Rejections Matter for the U.S. Economy

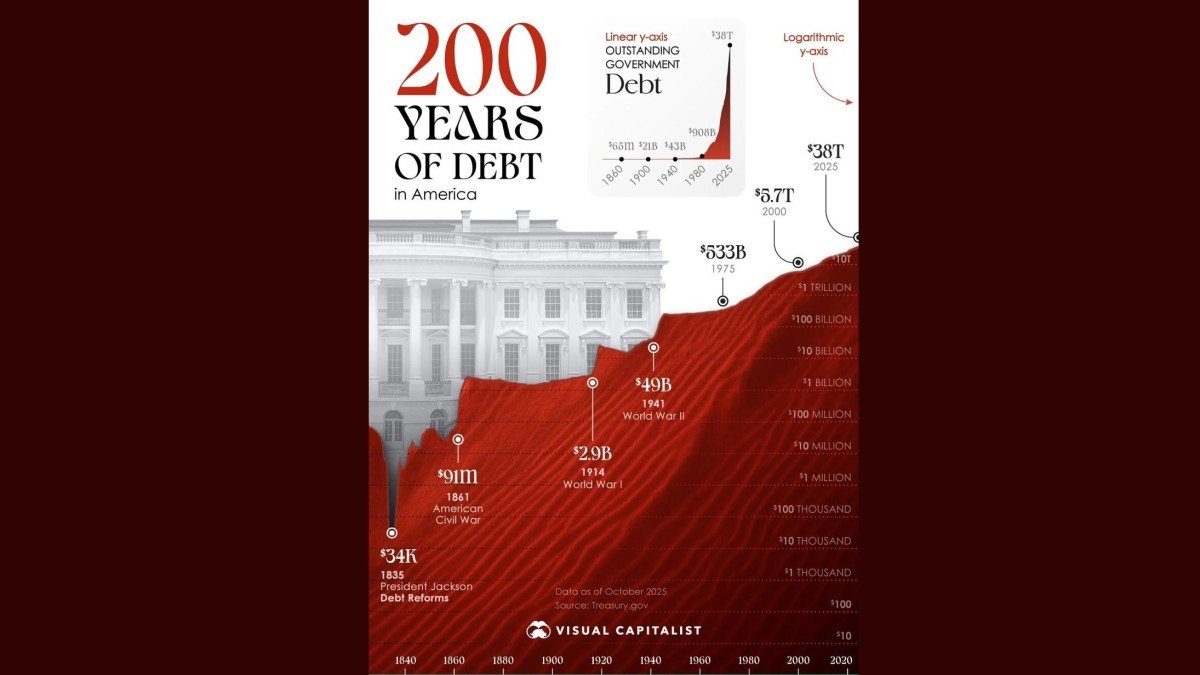

Student debt has long been treated as a personal problem: a matter between a graduate and their lender. But when more than 42 million Americans owe over 1.6 trillion USD in student loans, the line between individual finance and macroeconomics starts to blur. What happens to these borrowers in aggregate can shape everything from housing demand to car sales and even recession risk.

That is why the recent data from the U.S. Department of Education deserves more attention than just a passing headline. In August alone, the Department rejected roughly 328,000 applications for income-driven repayment (IDR) plans—programs that cap monthly payments based on income and promise eventual forgiveness after many years of consistent payments. Another 800,000+ applications remain in limbo, waiting to be processed.

At first glance, this might sound like an administrative issue. In reality, it is a stress test of the social contract behind higher education finance and a reminder that household debt can either act as a stabilizer or as a drag on growth, depending on how it is managed.

1. What Income-Driven Repayment Is Actually Designed to Do

Income-driven repayment plans were created to solve a simple but powerful problem: fixed payments do not adjust when life does. Graduates whose earnings are volatile or lower than expected can find themselves facing a monthly bill that simply does not match their paychecks. Borrowers can then fall behind, enter delinquency, or default—outcomes that damage credit scores, limit access to housing and car loans, and in some cases restrict professional licenses.

IDR plans attempt to break that cycle by tying monthly payments to a percentage of discretionary income and extending the repayment period. When implemented well, the design has several benefits:

- Affordability: Payments rise and fall with income, reducing the chance that a temporary setback leads to long-term financial damage.

- Default prevention: If borrowers can stay current, even with small payments, they are less likely to enter default or face collection actions such as wage garnishment.

- Eventual forgiveness: After a set number of years in good standing, remaining balances can be forgiven, offering a clear horizon rather than endless repayment.

In theory, this makes student debt more like a contingent tax than a traditional loan—a share of income rather than a fixed bill. But for that concept to work, borrowers need to be able to access the plans in the first place.

2. Why 328,000 Rejections Are a Big Deal

The Department of Education has said that many rejections stem from ambiguity in how borrowers selected their plans. A common option on the application is to simply pick the lowest possible payment, rather than naming a specific program. According to officials, this phrasing created confusion and, under current rules, led to applications being denied rather than corrected.

On paper, borrowers are allowed to reapply and specify a concrete plan. In practice, this is far from trivial:

- Reapplying takes time, documentation, and often a level of financial literacy that many borrowers do not have.

- During the gap, borrowers can be placed into standard repayment schedules with higher monthly obligations or into forbearance, where interest still accrues.

- The uncertainty itself—waiting while over 800,000 applications remain pending—creates anxiety that can affect spending decisions even before payments adjust.

The result is a group of hundreds of thousands of people who expected a soft landing into income-based plans but instead face higher bills or administrative limbo. The timing makes this even more significant, because another policy is about to restart.

3. Wage Garnishment Returns: Less Slack in Household Budgets

Beginning in January, the Department of Education plans to resume wage garnishment for defaulted student loans. This means that employers can be instructed to withhold part of a borrower’s paycheck to cover unpaid obligations. For households already facing higher living costs, the combination of:

- rejected IDR applications,

- pending reapplications, and

- the prospect of automatic deductions from wages

creates a very tight squeeze.

Unlike some other types of consumer debt, student loans are generally difficult to discharge through bankruptcy. Courts can allow discharge in rare cases of exceptional hardship, but the legal threshold is high and uncertain. In practice, this turns student debt into something close to a long-term obligation that follows borrowers even through periods of unemployment or illness.

When garnishment resumes, borrowers with unresolved repayment plans will have fewer choices. Their monthly budgets will adjust not based on what they can comfortably pay, but on what is legally withheld. For many families, that shift will show up in reduced spending on essentials and delayed plans for major purchases.

4. From Individual Stress to Macro Headwind

It is tempting to think of 328,000 rejected applications as a small slice of the 42 million Americans with student loans. But the impact is not linear. Many of these borrowers are in exactly the life stages that drive consumption: forming households, buying cars, starting families and building careers.

Higher required payments or uncertainty around repayment options can influence the economy through several channels:

4.1 Housing

Monthly student loan obligations are a key factor in mortgage underwriting. When payments rise or remain unpredictable, lenders may see higher debt-to-income ratios and become more cautious. This can mean:

- Delayed home purchases and longer periods of renting.

- Lower demand in certain housing markets, especially in regions with high concentrations of indebted graduates.

- Reduced home improvement spending, as borrowers prioritize liquidity over upgrades.

4.2 Auto sales and transportation

For many households, the first place to cut when budgets tighten is discretionary or semi-discretionary categories like new vehicles. Higher student loan payments can translate into:

- Postponed car purchases or choosing cheaper used vehicles.

- Less willingness to take on additional auto loans, affecting both manufacturers and lenders.

4.3 Everyday consumption

Even modest changes in monthly obligations add up. When borrowers redirect an extra 100–200 USD each month toward student loans, that is money not being spent at local restaurants, retailers, or service providers. In aggregate, this can soften consumption, especially in communities with many recent graduates.

4.4 Financial stability

Finally, higher default rates on student loans can feed into a broader sense of financial insecurity. While student loans are primarily a government-held asset rather than a bank balance sheet risk, rising defaults can still influence sentiment in credit markets and add to concerns about household debt sustainability.

5. A Design Problem, Not Just a Discipline Problem

It is easy to frame the situation as a story about personal responsibility: borrowers took on debt and now must repay it. But the current controversy highlights something more subtle: how the structure and administration of repayment programs can shape economic outcomes just as much as individual choices.

The fact that so many applications were rejected because borrowers selected an ambiguous option—"pay the lowest amount"—is revealing. It suggests that:

- The user interface of public policy matters. If the default choice on a form leads to confusion, that is a design bug, not simply a borrower error.

- Complexity itself can act as a regressive tax. More educated or better-advised borrowers are more likely to navigate the forms correctly, while others bear the cost of mistakes.

- Administrative capacity is a real constraint. When hundreds of thousands of applications pile up, delays are inevitable, and uncertainty becomes a hidden cost.

In other words, the challenge is not only whether the government offers income-driven plans, but whether the path into those plans is clear, predictable, and resilient.

6. What Borrowers Can Do — and the Limits of Individual Action

From a practical, educational perspective, affected borrowers are being advised to:

- Re-submit their applications and explicitly choose a specific income-driven program rather than simply selecting the lowest payment option.

- Track communication from loan servicers and the Department of Education carefully, especially as wage garnishment policies are reinstated.

- Seek independent guidance from non-profit credit counseling organizations or trusted financial advisors if the available choices feel unclear.

These steps are important, but they also highlight the limits of purely individual strategies. Even the best personal planning cannot fully offset systemic issues such as processing delays, ambiguous forms, or sudden policy shifts. This is why student loans continue to be a focal point in broader discussions about the cost of education and the role of government in managing long-term human capital investments.

7. Why Markets Should Care

For investors, student loan policy can seem far removed from topics like interest rates, corporate earnings, or digital assets. Yet there are several reasons why it deserves a place in macro analysis:

• Consumption sensitivity: Younger households have a high marginal propensity to consume. Changes in their obligatory payments can have an outsized effect on sectors such as retail, hospitality, and entry-level housing.

• Labor mobility: Heavy debt burdens and uncertain repayment terms can reduce willingness to take entrepreneurial risk or relocate, subtly affecting productivity and innovation.

• Policy feedback loops: If default rates rise or public dissatisfaction grows, it can lead to renewed debates on forgiveness programs, budgeting, and higher-education funding models—each with potential impacts on bond markets and fiscal expectations.

From this vantage point, the 328,000 rejected applications are not just a human-interest story. They are a data point in a larger question: how much financial flexibility do U.S. households really have in an environment of higher interest rates and elevated living costs?

8. Looking Ahead: Possible Paths Forward

The immediate policy response may focus on the mechanics of the application process—clarifying options on forms, improving guidance from servicers, and prioritizing the backlog of pending applications. But in the medium term, several broader ideas are likely to remain in the conversation:

- Simplified repayment structures that reduce the number of plan types and minimize the risk of choosing incorrectly.

- Automatic enrollment into income-driven plans for eligible borrowers, with an opt-out rather than an opt-in structure.

- Greater data sharing between tax authorities and loan servicers (within clear privacy boundaries) to streamline income verification and reduce paperwork.

- Reforms to bankruptcy treatment, which some policymakers argue should include clearer conditions under which student debt can be restructured or discharged.

Each of these approaches carries trade-offs. But they all point toward the same underlying recognition: student debt is now a macro variable, not just a micro one. How it is managed will influence not only millions of individual households, but also the strength and resilience of the broader U.S. economy.

9. Conclusion: A Quiet but Important Warning Signal

The rejection of more than 300,000 income-driven repayment applications is not as dramatic as a market crash or a banking crisis. There are no flashing red charts on trading screens. Yet it is still a warning signal.

It tells us that a significant number of borrowers who were counting on flexible repayment are instead facing higher obligations or administrative uncertainty. It coincides with the return of wage garnishment for defaulted loans and occurs against a backdrop of persistent cost-of-living pressure. Together, these factors reinforce a simple but powerful lesson: when essential debts are hard to adjust, they can become a drag not just on individuals but on growth itself.

For policymakers, the message is that the design and execution of repayment systems matter as much as headline promises. For investors, it is a reminder that consumer balance sheets are a critical part of any macro story. And for borrowers, it underscores the importance of engaging early, understanding options, and seeking guidance—even when the system itself feels complex.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and analytical purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or legal advice. Individuals facing student loan obligations should consult official resources and qualified professionals before making decisions about repayment plans or legal strategies.