Tariffs, Tax Cuts and a Growing Debt Mountain: Why U.S. Public Debt Keeps Rising

The headlines sound contradictory at first glance. On one side, the United States has collected over 200 billion USD in new tariff revenue in 2025 from measures introduced under President Trump. Part of that money is already being recycled into targeted support for farmers, and the administration has floated the idea of a 2,000 USD 'tariff dividend' for eligible households.

At the same time, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is telling workers to expect sizable income-tax refunds of 1,000–2,000 USD per household in the first quarter of 2026, as the effects of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act flow through the tax system. On paper, tax cuts can feel like free money.

Yet behind these seemingly generous measures lies a harder macro reality. The very same legislation that lowers taxes and promises refunds also raises the projected U.S. public debt by about 3.4 trillion USD over the next decade, before interest costs. To make space for that borrowing, Congress has already lifted the federal debt ceiling by roughly 5 trillion USD, giving the government room to finance larger deficits.

This piece unpacks how these elements fit together: why tariff revenue does not come close to offsetting the cost of tax cuts and higher spending, how the short-term boost to households sits alongside a longer-term debt trajectory, and what all of this means for investors who are trying to understand the fiscal backdrop for bonds, equities and digital assets.

1. Tariffs: Big Numbers, Small Relative Impact

Let us start with the tariff side of the ledger. In 2025, the United States has generated more than 200 billion USD in additional tariff income from new and higher import duties. Of that, around 12 billion USD has been earmarked to compensate farmers and agricultural communities affected by the ongoing trade tensions with China.

Two points are crucial here:

- Tariffs are a form of tax. They are collected at the border, but the economic burden is ultimately shared between foreign producers, U.S. importers and domestic consumers through higher prices or lower margins.

- Even large-sounding tariff sums are modest relative to the federal budget. With total federal spending in the 6–7 trillion USD range and an annual deficit often above 1.5 trillion USD, an extra 200 billion USD is meaningful but not transformative.

In fiscal terms, the new tariffs are best understood as a partial offset to other policy choices, not as a complete solution to the debt problem. Once the 12 billion USD allocated to farmers is removed, the net contribution is smaller still.

When policymakers speak about using tariff revenue to fund a 2,000 USD 'tariff dividend' for eligible Americans, they are implicitly treating that revenue as a pool of money that can be redistributed. But unless other spending is cut or other taxes are raised, any such dividend would simply shift where the money goes on the spending side, not fundamentally change the deficit picture.

2. Tax Cuts, Refunds and the Short-Term Sugar High

If tariffs are one pillar of the current fiscal mix, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act is the other. Passed in July 2025, this legislation combined large-scale tax reductions with significant increases in federal spending on defence, border security and selected federal programmes.

Because many households did not immediately adjust their withholding or estimated tax payments when the law took effect, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent now expects that millions of families will receive unexpectedly large refunds in early 2026. The typical range mentioned is 1,000–2,000 USD per household.

That dynamic has several important implications:

• Short-term demand boost. A wave of refunds can support consumption in the near term, particularly for households that have been squeezed by higher living costs. It can function like a temporary stimulus.

• Lower effective tax burden. Over time, if tax schedules remain unchanged, households will likely adjust their withholding and the surprise element will disappear. The underlying reality, however, is that the government is collecting less revenue per dollar of income than before the Act.

• Higher structural deficits. Unless offset by spending cuts, a lower tax take means that, at any given level of spending, deficits will be larger. That is exactly what the Congressional projections show: a wider gap between revenue and expenditure, even when tariff collections are included.

From an educational perspective, this is a classic example of the difference between cash flow timing and long-term budget balance. In the short run, refunds feel like a windfall to households and can temporarily lift economic activity. In the long run, the government still needs to finance the gap between what it spends and what it collects. That financing comes from issuing more debt.

3. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act and the Mechanics of Higher Debt

The mechanics behind the projected 3.4 trillion USD increase in public debt over ten years are not mysterious. They are, in fact, straightforward arithmetic.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act does three broad things at once:

- Reduces tax revenue. By lowering various tax rates and thresholds, it cuts the federal government’s income from individuals and businesses.

- Raises expenditure. It ramps up spending on defence, border enforcement and certain domestic programmes, reflecting policy priorities set by the administration and Congress.

- Leaves core entitlement programmes largely intact. Social Security, Medicare and other large programmes continue on pre-existing trajectories that are already expensive due to population ageing and healthcare costs.

The net result is a larger annual deficit than would have existed without the Act. If the government runs, for example, an extra 300–400 billion USD of deficit per year on average over the next decade, it will accumulate roughly 3.4 trillion USD of additional debt by the end of that period, even before accounting for interest on that debt.

Because the U.S. already started from a high debt base, the compounding effect is substantial. As total public debt grows, so do interest payments. When interest rates are higher than in the 2010s, those payments can quickly become one of the largest single line items in the federal budget.

Recognising this, policymakers have raised the statutory debt ceiling by around 5 trillion USD. That does not, by itself, force the government to borrow. It simply removes a technical constraint and acknowledges that, under current policy, borrowing is likely to rise. In other words, the ceiling has been adjusted to accommodate the path implied by the Act, rather than to hold it back.

4. Why Tariffs Cannot 'Pay for' the New Debt

A natural question is whether the 200 billion USD in annual tariff revenue can offset some or all of the new borrowing. The answer is: only at the margin.

To see why, imagine a simple comparison:

- Tariff revenue: roughly 200+ billion USD in 2025, a figure that may fluctuate with trade volumes and tariff schedules.

- Additional debt from the Act: roughly 3.4 trillion USD over ten years, or an average of 340 billion USD per year if evenly distributed.

Even if tariffs remained at current levels, they would cover only a portion of the incremental deficit created by the tax cuts and spending increases. And that is before considering other factors such as economic cycles, changes in interest costs and unforeseen fiscal shocks.

In practice, tariff revenue also has opportunity costs. A portion is already being used to support farmers affected by trade frictions. A future tariff dividend would carve out another slice. The more that tariff income is earmarked for specific programmes or transfers, the less it can contribute to narrowing the overall gap between revenue and expenditure.

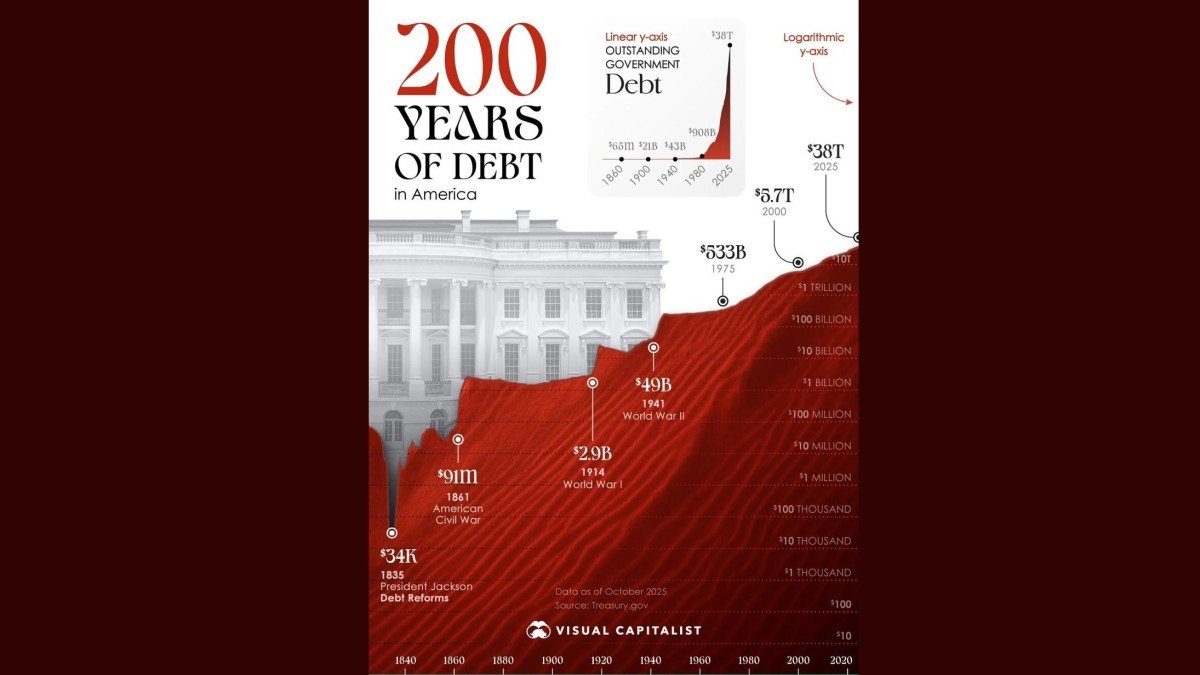

This is not unique to the current administration. Historically, governments of all political stripes have often overestimated the degree to which new revenue sources can offset ambitious tax cuts or spending plans. The U.S. today is simply the latest example of a familiar pattern: ambitious fiscal policy choices pushing debt higher even in the presence of new taxes.

5. Short-Term Boost vs. Long-Term Sustainability

For households and markets, the mixed impact of these policies can be summarised as a tension between the short term and the long term.

5.1 In the short term

- Refunds and lower taxes boost disposable income.

- Tariff-funded support programmes help targeted groups such as farmers.

- Higher government spending supports demand in sectors linked to defence and infrastructure.

These effects can cushion the economy against headwinds, particularly when growth is soft or when labour-market data — such as rising unemployment — hint at a risk of slowdown. They can also support corporate revenue and, by extension, equity markets in the near term.

5.2 In the long term

- Structural deficits remain large, even with higher tariffs.

- Debt continues to climb, increasing exposure to interest-rate risk.

- Future policymakers face harder choices: raise taxes, cut spending, or accept a permanently higher debt ratio.

Higher debt is not automatically a crisis. The United States benefits from issuing the world’s primary reserve currency and from deep capital markets that can absorb large volumes of Treasury securities. But as the debt stock rises, investors will pay closer attention to the combination of growth, inflation and political willingness to manage the budget.

6. What It Means for Bonds, the Dollar and Alternative Assets

From an educational investing perspective, the fiscal path laid out by current policy has implications across several asset classes.

6.1 Government bonds

More borrowing means more Treasury issuance. If global demand for U.S. debt keeps pace, yields can remain contained. If demand weakens at the margin, yields may have to rise to attract buyers, especially at longer maturities. In that scenario, interest costs could consume an even larger share of the budget, reinforcing concerns about sustainability.

6.2 The U.S. dollar

Persistent deficits and rising debt can, over very long horizons, influence confidence in a currency. In the short and medium term, however, the dollar’s strength is shaped more by relative interest rates, growth differentials and global risk sentiment than by fiscal arithmetic alone. A world in which the U.S. remains one of the strongest major economies may still see robust demand for dollar assets even as debt climbs.

6.3 Real assets and digital assets

For some investors, a steadily rising public debt ratio is one of the reasons to hold real assets such as real estate, infrastructure, precious metals or digital assets like Bitcoin as a long-term hedge against currency dilution. The logic is straightforward: if governments are likely to rely on borrowing and, over time, on inflation to manage debt, then owning scarce or non-sovereign assets can provide diversification.

It is important, however, to distinguish between macro narrative and price action. Digital assets, for example, can be extremely volatile in the short run and may fall sharply even in an environment of expanding public debt, especially when leverage is unwound or when regulatory news affects sentiment. The fiscal backdrop is one factor among many, not a one-way price guarantee.

7. Key Educational Takeaways

Stepping back from the daily headlines, several broader lessons emerge from the current U.S. fiscal debate:

• Tariff revenue is meaningful but limited. Hundreds of billions of dollars sound large, but must be compared with annual deficits that already run into the trillions. Tariffs can shift the composition of revenue and spending, not eliminate deficits by themselves.

• Tax cuts and refunds feel good now, but show up later in the debt figures. When governments collect less relative to what they spend, the difference is financed by borrowing. That borrowing does not disappear because some of it is hidden in the form of pleasant surprises at tax time.

• Debt ceilings are political tools, not economic brakes. Raising the ceiling by 5 trillion USD does not, by itself, cause the debt to rise. It acknowledges that, under current policy, borrowing will likely reach that level.

• Short-term stimulus and long-term sustainability often pull in opposite directions. Policies that support demand today can make the future debt path steeper if they are not paired with offsetting measures.

• Investors should focus on trends, not just single-year numbers. What matters for fiscal sustainability is the combination of growth, interest costs and the primary balance (the deficit before interest), measured over many years.

From a long-horizon perspective, the most likely scenario is not an abrupt fiscal crisis, but a gradual normalisation of higher debt levels as part of the economic landscape. That environment favours thoughtful diversification, an understanding of how different assets respond to inflation and interest-rate shifts, and a clear view of one’s own risk tolerance.

Tariffs, tax refunds and high-profile legislation such as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will continue to generate headlines. Behind those stories, the underlying arithmetic remains simple: as long as the United States chooses to spend more than it collects, even in years of strong tariff receipts, public debt will keep trending higher. Understanding that basic relationship is essential for anyone trying to connect macro policy to their investment decisions.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment, legal or tax advice. Fiscal policy is complex and subject to change. Always conduct your own research and consult a qualified professional before making financial decisions.