Kashkari’s “Near Neutral” Message: Why the Next Phase Is Less About Rate Cuts—and More About the Shape of Work

In the late stages of a tightening cycle, central bankers tend to speak in smaller numbers and bigger implications. When Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari argues that rates are already close to “neutral,” the headline looks simple: the Fed may not need many additional cuts. But the real story is not the arithmetic. It’s the trade-off hidden inside that word “neutral”—a theoretical level where policy is neither accelerating the economy nor restraining it.

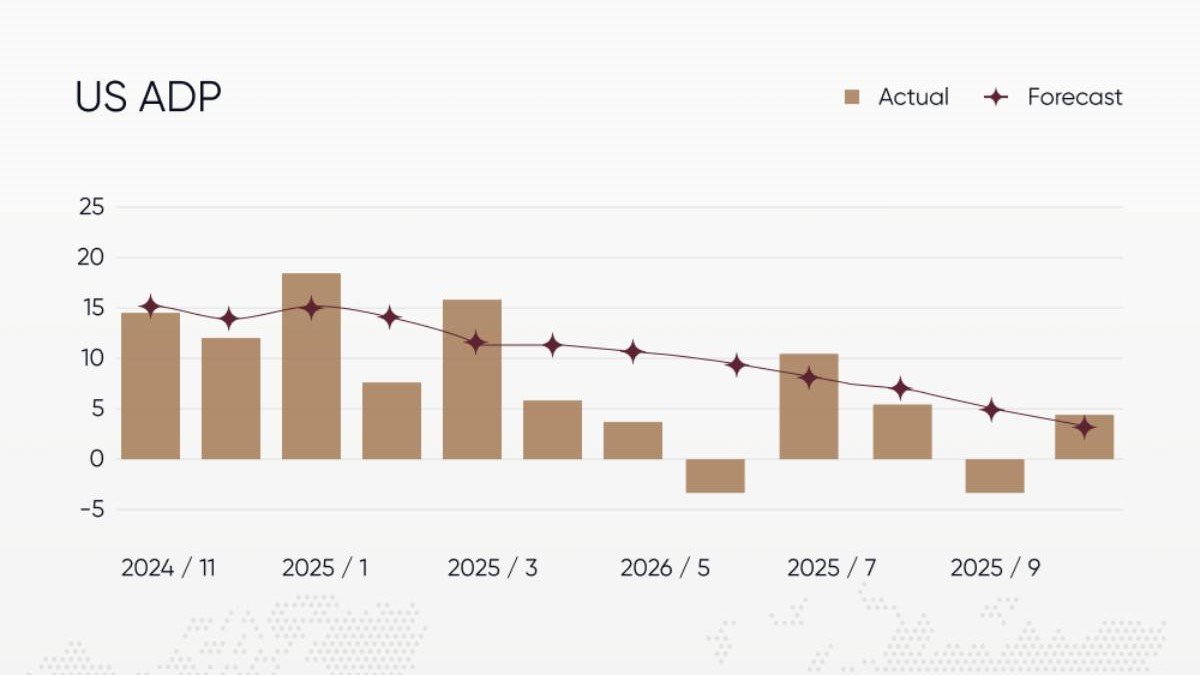

In 2026, the most important question may not be whether the next move is one cut or two. It may be whether the labor market is slowing for the “good” reasons (productivity gains and efficient matching) or the “quietly dangerous” reasons (hiring hesitation, slower churn, and reduced mobility). Kashkari’s comments about AI making big firms slower to hire point to a new kind of cooling—one that can feel stable on the surface while becoming harder for individuals underneath.

1) The neutral rate is not a destination—it’s a balancing act

The neutral rate is often described as if it were a single, discoverable point on a map. In reality, it is an estimate that moves with the economy’s structure: demographics, productivity, global savings, fiscal policy, and risk appetite. That’s why “near neutral” is less a precise GPS coordinate and more a signal that the Fed believes policy is no longer doing heavy lifting in either direction.

Using the framing provided—policy rates around 3.5%–3.75%, roughly 0.5% above the Fed’s neutral estimate—the implication is that the Fed is approaching a zone where every additional cut becomes more consequential. Early cuts can be “normalization.” Late cuts can become “stimulus,” even if they don’t look dramatic in isolation.

What this changes in practice:

• The conversation shifts from “How fast can we get back to normal?” to “How do we avoid reigniting inflation while growth cools?”

• Markets may react less to the direction (cut vs. hold) and more to the tone: confidence, caution, and the conditions for the next move.

Neutral, in other words, is where the Fed becomes more sensitive to second-order effects: who is hiring, who is struggling, and which prices are still rising for structural reasons.

2) The Fed’s real dilemma: inflation that lingers, labor that quietly slows

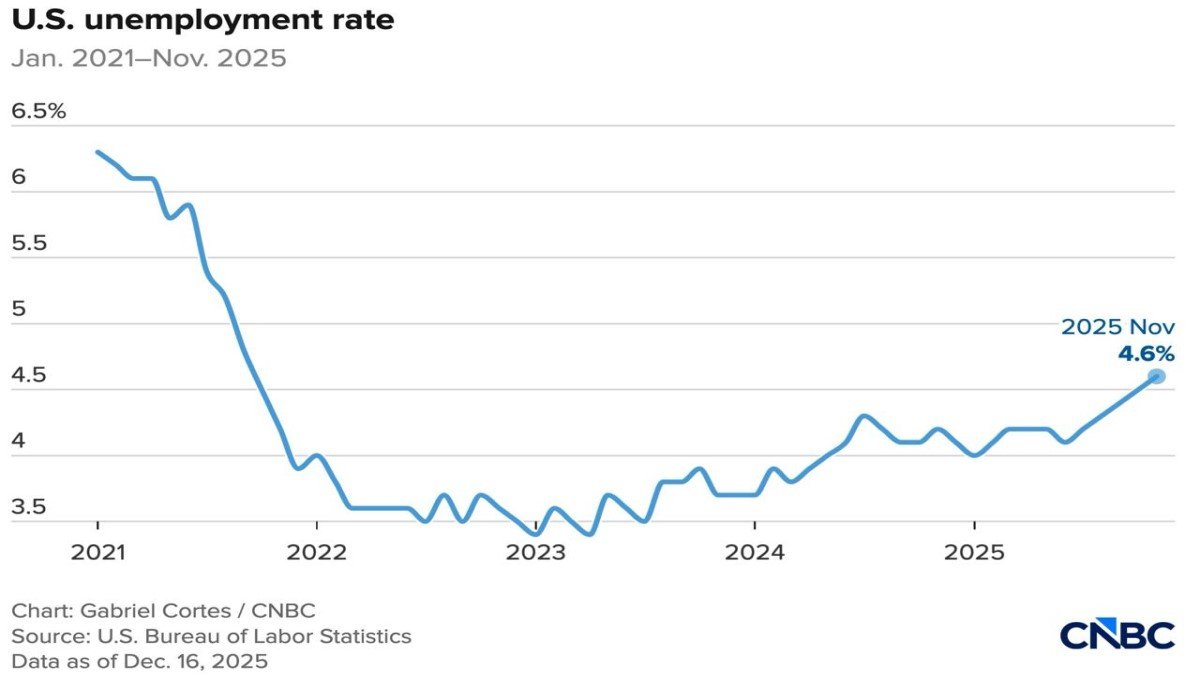

Kashkari’s balancing act is the familiar dual mandate problem, but with a 2026 twist. On one side: inflation is not fully “done,” with core inflation described around 2.8%. On the other: unemployment has drifted higher, cited around 4.6%. That combination doesn’t scream crisis. It whispers “tension.”

Whispering tension is harder for policy, because it tempts everyone to overfit the narrative. Optimists see inflation trending down and assume victory. Pessimists see labor softness and assume recession. A more realistic reading is that the economy can enter a middle zone: inflation persists in certain categories while job creation slows without collapsing.

Why this zone is tricky:

• Inflation can remain sticky even as growth cools, especially if it’s driven by policy shocks (like tariffs), housing dynamics, or supply constraints.

• Labor markets can weaken through fewer openings rather than mass layoffs—painful for job seekers, but not immediately visible in headline unemployment.

This is why Kashkari’s warning about inflation risks lasting for years matters. If inflation persistence is structural, the Fed can’t “cut its way” out without risking a rebound. If labor slowing is structural, holding rates too high can increase friction for workers trying to move or re-enter.

3) Tariffs as an inflation amplifier: not always huge, but often stubborn

Tariffs are politically loud, but their inflation impact can be economically subtle. The key distinction is between the price level and the inflation rate. Tariffs can create a one-time jump in prices (a level shift), but if supply chains reconfigure slowly or if firms keep pricing power, that “one-time” jump can echo through contracts, wages, and expectations.

Kashkari’s concern—tariff effects prolonging inflation—should be read as a risk-management statement. The Fed worries less about a single month’s data and more about whether businesses begin to assume higher input costs as the new normal, embedding them into pricing behavior.

How tariffs can keep inflation sticky:

• Substitution takes time: replacing suppliers is not instantaneous, especially for specialized components.

• Cost pass-through can be gradual: firms may raise prices in stages to avoid demand shocks.

• Expectations matter: if businesses and consumers expect higher costs, “temporary” becomes “persistent.”

Even if tariffs do not explode inflation, they can reduce the Fed’s confidence that inflation will glide cleanly back to target—making the central bank more cautious near neutral.

4) AI slowing hiring: a new kind of cooling that looks stable until you zoom in

Kashkari’s most forward-looking point is about AI. The claim is not that AI is causing mass layoffs; it’s that AI is making large companies slower to hire because productivity is improving. This is a meaningful distinction. An economy can cool through reduced hiring rather than increased firing—and that tends to feel “fine” at the aggregate level while becoming frustrating at the individual level.

Think of it as labor-market viscosity. People keep their jobs, so layoffs don’t spike. But fewer new roles open up, so people who lose a job—or want a better one—face longer searches. The result can be a labor market that is stable in headlines but less forgiving in lived experience.

Why the “less hiring, fewer layoffs” regime matters:

• Job switching slows, which can reduce wage growth without a dramatic rise in unemployment.

• Entry-level and mid-level pathways can narrow if firms rely more on automation and internal upskilling.

• Big firms may lead the trend, while small businesses feel it later—creating uneven data and mixed signals.

This dynamic also changes how we interpret unemployment. A rising unemployment rate can reflect slower re-entry rather than a sudden collapse in demand. Policymakers then face a tougher question: how to support mobility and opportunity without fueling another inflation wave.

5) What this macro mix can mean for markets—and for crypto as a sentiment barometer

Near-neutral policy, sticky inflation risk, and AI-shaped hiring all point to a market environment where the biggest driver is not dramatic easing or dramatic tightening, but uncertainty about the equilibrium. In such regimes, markets can become more sensitive to incremental data: labor reports, inflation prints, and forward guidance.

For risk assets, the implication is not a single-direction forecast. It’s a change in the type of volatility. When the Fed is near neutral, surprises matter more than trends. A slightly hotter inflation print can change the expected path of cuts. A slightly weaker hiring print can revive growth concerns. This can produce choppy conditions even without a recession narrative.

Crypto often reflects this “macro sensitivity” in a compressed way because it sits at the intersection of liquidity conditions and risk appetite. If markets believe cuts are limited, leverage becomes more expensive and speculative excess can cool. If markets believe growth is slowing but policy is constrained by inflation, investors may seek assets perceived as alternative stores of value—though those perceptions can vary widely and can shift quickly.

The educational takeaway is simple: in a near-neutral world, it’s less about predicting a single event and more about watching the balance between inflation persistence and labor-market cooling. That balance will shape liquidity, risk tolerance, and the narrative investors attach to both traditional assets and digital assets.

Conclusion

Kashkari’s message about being close to neutral is not just a comment on the number of rate cuts left. It’s a warning that policy is approaching a sensitive zone where mistakes are easier to make and harder to reverse. If inflation remains stubborn—especially with tariff-related uncertainty—while AI quietly reduces hiring urgency at large firms, the economy may cool in a way that feels calm but becomes less flexible for workers.

Markets, as always, will price consequences rather than intentions. In 2026, the consequential variables may be productivity, hiring behavior, and inflation persistence—not headline growth alone. The more “normal” the surface looks, the more important it becomes to understand the mechanisms underneath.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does “neutral interest rate” actually mean?

It’s an estimated policy rate that neither stimulates nor restrains the economy. It isn’t directly observable and can shift over time with productivity, demographics, fiscal conditions, and global capital flows.

Why would being near neutral imply fewer rate cuts?

If policy is close to neutral, additional cuts can become more stimulative. If inflation is still elevated, the Fed may prefer to move cautiously to avoid re-accelerating price pressures.

How can AI slow hiring without causing layoffs?

If productivity rises, firms can meet output goals with fewer new hires. That can reduce job openings and slow labor-market churn, making it harder for job seekers even if layoffs remain limited.

Why do tariffs matter for inflation over multiple years?

Tariffs can raise costs and alter supply chains. Even if the initial impact is a price-level jump, slow substitution and gradual pass-through can keep inflation pressures sticky.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. Economic data and policy views can change as new information emerges. Markets involve risk, and no outcome is guaranteed. Consider your own circumstances and consult qualified professionals before making decisions.