Venezuela’s Alleged “Shadow Bitcoin Reserve”: What Markets Would Really Price If 600,000 BTC Became a Seized Asset

Some headlines land like fireworks: bright, loud, and gone. Others land like a new coordinate on the map. The claim that Venezuela may control roughly 600,000–660,000 BTC (often framed as “$60B+”) is not interesting because it is sensational. It’s interesting because it forces a different kind of question: what happens when Bitcoin stops being just an investor asset and starts behaving like a sovereign balance-sheet object—something that can be frozen, seized, or converted into strategic leverage?

To be clear, the exact number is difficult to verify from the outside. Bitcoin is transparent on-chain, but attribution is not. Large holdings can be split across wallets, routed through intermediaries, or parked in custody structures that obscure ownership. So the purpose of this analysis is not to certify an inventory figure. The purpose is to examine the market consequences of the scenario the claim implies: a state-sized Bitcoin trove moving from “contested and mobile” to “seized and administratively controlled.”

1) Why this claim matters even if the number is wrong

Markets don’t require perfect truth to price risk. They require a believable distribution of outcomes. If a credible share of participants begins to assign non-trivial probability to a sovereign entity holding hundreds of thousands of BTC, that belief becomes part of the risk surface—just like a central bank rumor can move FX even before policy changes.

The deeper reason this story matters is that it reframes Bitcoin from a purely market-driven asset into a potential geopolitical artifact. When an asset becomes entangled with sanctions, custody, seizure, and state policy, price discovery starts reflecting more than flows and halving cycles. It starts reflecting legal and institutional pathways—the plumbing of who can hold, who can move, and who can be forced to stop moving.

2) The chart is a narrative weapon (and narratives move faster than coins)

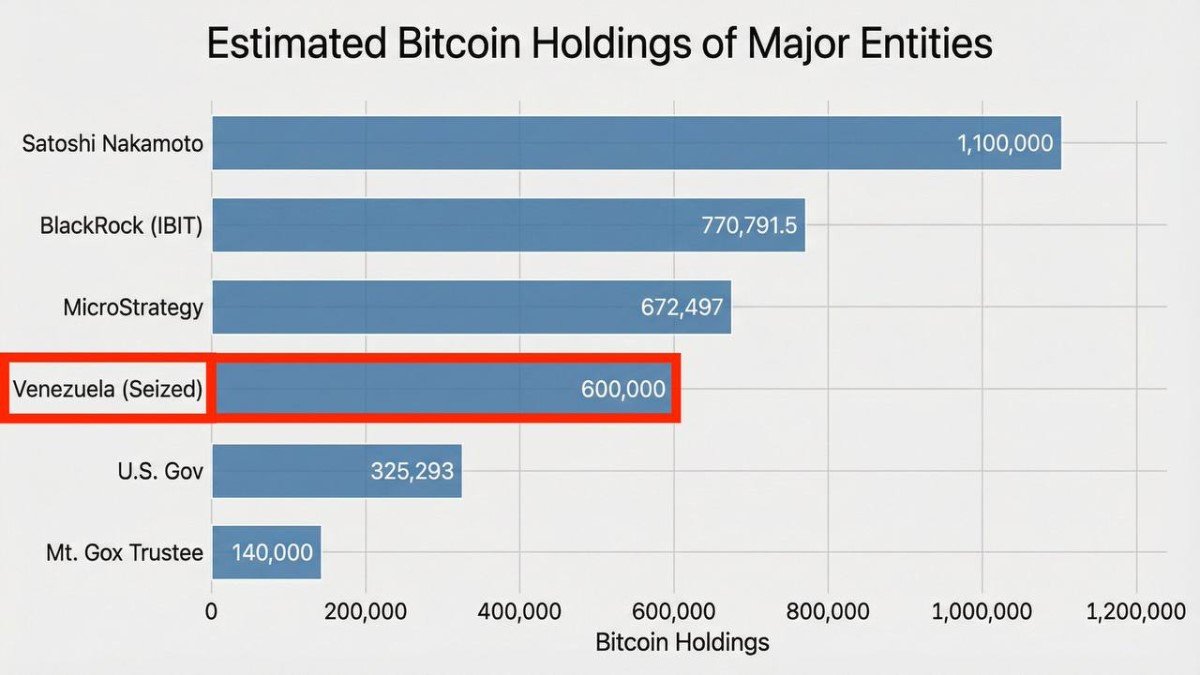

The attached chart, titled “Estimated Bitcoin Holdings of Major Entities”, places “Venezuela (Seized)” at 600,000 BTC, alongside other well-known categories: Satoshi Nakamoto (1,100,000), BlackRock (IBIT) (770,791.5), MicroStrategy (672,497), the U.S. government (325,293), and the Mt. Gox trustee (140,000). Whether each label is perfectly accurate is less important than what the comparison does psychologically.

It compresses a complex topic into a single visual hierarchy: “Venezuela is comparable to the biggest holders.” That’s why these charts spread. They are not just data; they are framing devices. And framing devices are how markets coordinate attention—especially in crypto, where attention is a primary input to liquidity.

3) How a “shadow reserve” could form—without turning this into a how-to

The claim describes accumulation since 2018 through resource-linked channels—oil sales, gold swaps, and other non-traditional settlement pathways designed to reduce reliance on the conventional banking system. At a high level, this is the logic of any shadow reserve: when access to mainstream settlement is restricted, value routes through whatever rails remain functional.

It’s important to keep the discussion educational and non-operational. We don’t need the mechanics to understand the market implication: if a country uses alternative rails for settlement, it can accumulate a portfolio of assets that behave differently from fiat reserves. Bitcoin, in this context, is not “a trade.” It is a portability instrument—an asset whose mobility and bearer-like properties can be attractive when conventional channels are constrained.

4) The real market event is not ‘Venezuela owns BTC’—it’s ‘BTC becomes frozen’

Investors often treat “a big holder” as a supply-overhang story: will they sell? That’s a retail framing. For sovereign-scale holdings, the more relevant distinction is between sellable supply and non-sellable supply. A coin that cannot move—because keys are lost, because custody is constrained, or because it is legally frozen—behaves differently from a coin sitting in a liquid treasury.

If the U.S. were to seize such an asset (or credibly move it into a frozen/controlled category), the immediate effect might actually be less selling pressure, not more. Seized assets do not necessarily hit the market quickly; they often enter long administrative timelines. The market would then trade a paradox: “big headline, fewer movable coins.” That’s why seizures can be structurally bullish in some contexts—even while being politically contentious.

5) “Strategic reserve” is not about profit—it’s about optionality

When people hear “strategic reserve,” they imagine a government trying to time the market. That’s rarely the best interpretation. Strategic reserves exist to create optionality under stress. Oil reserves exist because supply shocks are existential to an industrial economy. A digital-asset reserve, if it emerges, would exist because settlement shocks and financial sanctions can be existential to certain policy objectives.

In that sense, a seized BTC stockpile could sit in one of two political containers. Container A is frozen asset: held as leverage, bargaining collateral, or legal evidence. Container B is strategic reserve: held as an instrument of national financial optionality. Either container reduces free-float liquidity compared to a world where the same coins could be sold at will, and that liquidity reality can matter more than ideology in price formation.

6) What would the market impact be—practically?

Let’s avoid dramatic predictions and focus on mechanisms. If the market begins to believe that hundreds of thousands of BTC have transitioned into a frozen/seized category, you’d likely see impact across three layers: narrative, derivatives, and liquidity behavior.

Narrative layer: Bitcoin becomes more legible as a state-relevant asset. That can attract institutional curiosity (“this is no longer a fringe instrument”) while also attracting regulatory intensity (“this is now a policy variable”). Both can be true.

Derivatives layer: Large, uncertain inventory stories tend to express themselves in volatility markets first. Traders hedge scenario risk via options because options price uncertainty efficiently. Even without spot selling, implied volatility can rise if the distribution of outcomes widens.

Liquidity layer: If participants expect administrative freezing rather than immediate liquidation, they may treat the event as a “float tightening” narrative. That can support spot demand during risk-on windows. Conversely, if participants expect eventual auction-style selling, the market may price periodic supply events. The key is the expected timeline, not just the quantity.

7) The trust problem: why this story is also about proof, not price

One uncomfortable truth: the more Bitcoin becomes a geopolitical asset, the more the market will demand proof standards that crypto culture is not always good at providing. “A report says” can move sentiment for a day. But lasting repricing requires verifiable signals—on-chain trails, custody confirmations, or credible institutional disclosures.

This is where the chart’s wording matters. It labels the holding as “seized,” which implies a legal status shift that would normally come with documentation. If the market cannot find corroborating signals over time, the story decays into noise. If corroboration emerges, it hardens into a structural narrative: Bitcoin as a balance-sheet instrument that states can hold, lose, seize, and freeze.

8) The bigger picture: Bitcoin is drifting from ‘cycle asset’ to ‘state asset’

Crypto conversations often obsess over cycles—halving rhythms, post-halving years, and familiar playbooks. But the long-term maturation of Bitcoin has always pointed in another direction: integration into institutional and state-adjacent realities. ETFs made Bitcoin legible to retirement accounts. Corporate treasuries made it legible to balance sheets. Seizure and strategic-reserve talk makes it legible to governments.

If Venezuela truly holds a stash near the magnitude claimed, the market lesson isn’t “Venezuela is rich.” The lesson is that Bitcoin has become a kind of financial wildcard: a portable reserve that can sit outside conventional rails, and therefore becomes relevant precisely where conventional rails are weakest. That is a maturity signal—not a victory lap. Mature assets attract mature scrutiny.

Conclusion

The claim that Venezuela controls 600,000–660,000 BTC is, on its face, extraordinary—and therefore deserves careful skepticism. But markets don’t need certainty to care. They care because the scenario highlights a structural shift: Bitcoin’s role is expanding from a speculative instrument to a sovereign-adjacent asset that can be accumulated under constraint and potentially immobilized under law.

If a large BTC stash were seized and frozen, the immediate market consequence might not be a flood of selling, but a re-pricing of float, optionality, and policy risk. The market would trade the state-change: from “coins that might move” to “coins that can’t.” In a system where scarcity is the core narrative, immobility is not a footnote—it is the narrative.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can we verify that a country holds a specific amount of BTC?

Not reliably from the outside unless wallets are credibly attributed and monitored, or custody disclosures are provided. On-chain transparency shows movement, not identity. Attribution is the hard part.

Would a seizure automatically crash Bitcoin’s price?

Not necessarily. Seizure can imply freezing and long timelines. Markets may price uncertainty through volatility first, and the spot impact depends on whether participants expect coins to be sold quickly or immobilized administratively.

What does “strategic reserve” mean in practice?

A strategic reserve is about optionality under stress, not about short-term profit. If digital assets become strategic, they will be held (or frozen) to preserve leverage and flexibility during financial or geopolitical constraints.

Why does this matter to ordinary investors?

Because it changes the risk model. When an asset becomes state-relevant, it can face new sources of volatility (policy risk) and new sources of demand (institutional legitimacy). Understanding that tension is part of risk management.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. Claims about third-party or sovereign asset holdings may be incomplete, unverified, or subject to change. Market prices can be influenced by liquidity, positioning, and news flow. Always verify information using multiple credible sources and consider your own risk tolerance.