A Volatile Start to 2026: Venezuela, Multipolar Narratives, and Why ‘Hard Money’ Keeps Entering the Conversation

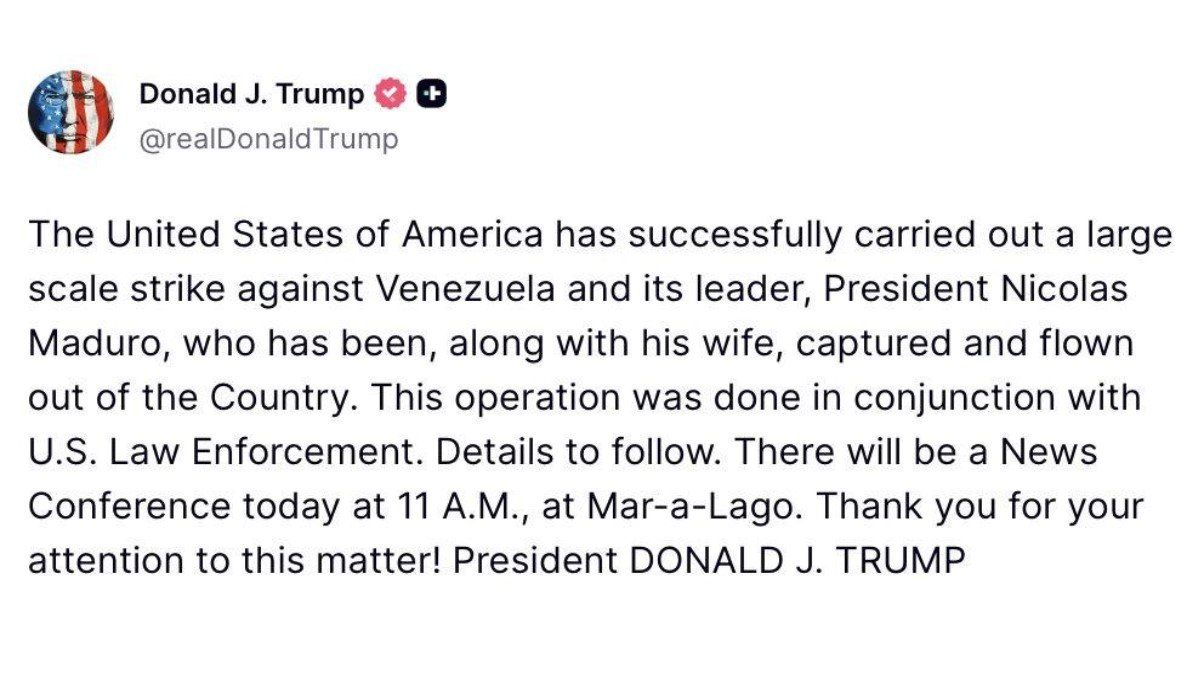

Some mornings don’t feel like a market open; they feel like a history exam. On January 3, 2026, major outlets reported that U.S. President Donald Trump said the United States carried out a large-scale strike in Venezuela and that President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were captured and flown out of the country. Whatever your politics, that is the kind of headline that forces investors, builders, and everyday observers to revisit first principles: what is risk, what is narrative, and what is simply a rumor dressed up as certainty?

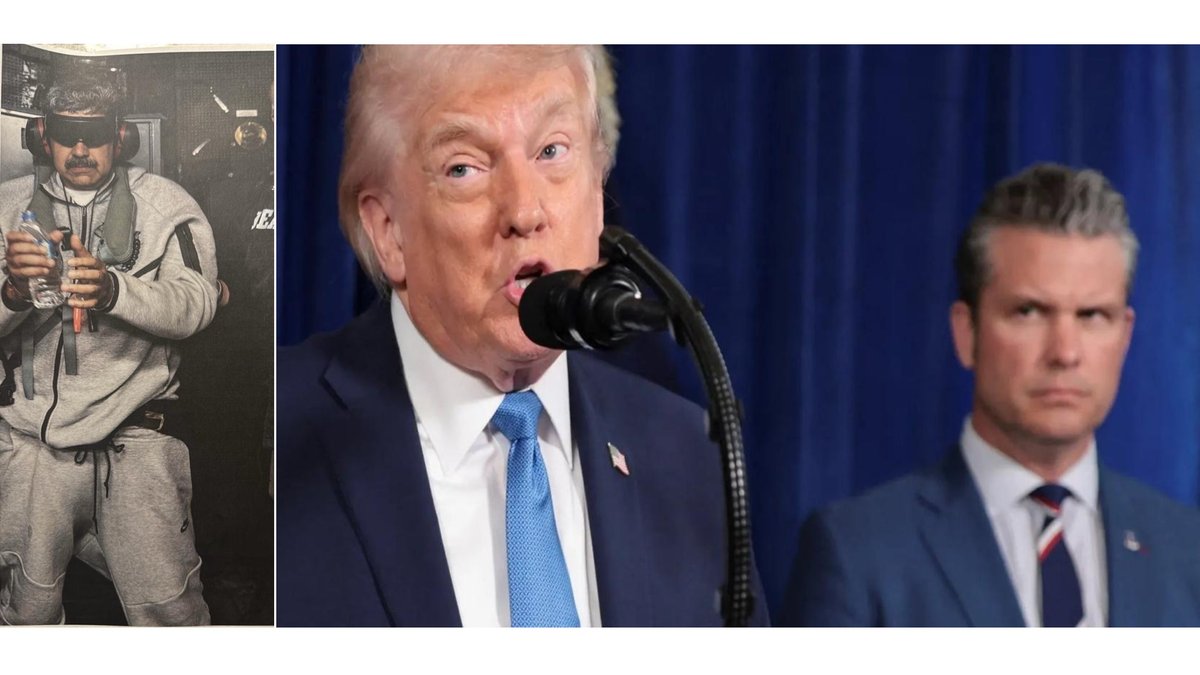

There is a second story running alongside the first: the information environment itself. In high-stakes events, the first wave of content is often the least reliable—recycled footage, mislabeled clips, and increasingly, synthetic media that looks “real enough” to spread. The market impact of a crisis is now inseparable from the media dynamics of a crisis. If you are trying to understand what this means for macro and crypto, that’s not a side note; it is the opening chapter.

1) What We Know, What We Don’t, and Why That Distinction Matters

In fast-breaking geopolitical events, the best habit is to separate “claims” from “confirmed details,” then update that line as reporting evolves. Reuters and AP reported that Trump said Maduro and Flores were captured and removed from Venezuela after a U.S. operation; AP also described plans for a temporary U.S. role during a transition and an intention to tap Venezuela’s oil. CBS reported similar statements about a large-scale strike and the pair being flown out. These are consequential assertions—worth taking seriously, and worth verifying carefully.

Precision matters because the first 24 hours of a crisis mix certainty and ignorance. You’ll see confident takes long before you see documentation. Markets move on partial information, which creates two kinds of volatility: price volatility and narrative volatility. The first is measurable; the second is psychological. Narrative volatility appears when people explain a complex event with a single story—“about oil,” “about drugs,” “about regime change”—and treat that story as settled. Early certainty can be an expensive habit, because it hardens before the facts do.

Practical takeaway: treat the first day as a mapping exercise rather than a conclusion. Identify what is sourced by major outlets, what is still disputed, and what is purely social-media inference. This simple discipline reduces the odds that you react to fiction with real money, real emotion, or real conviction.

2) Geopolitics as a Liquidity Event, Not Just a Foreign-Policy Event

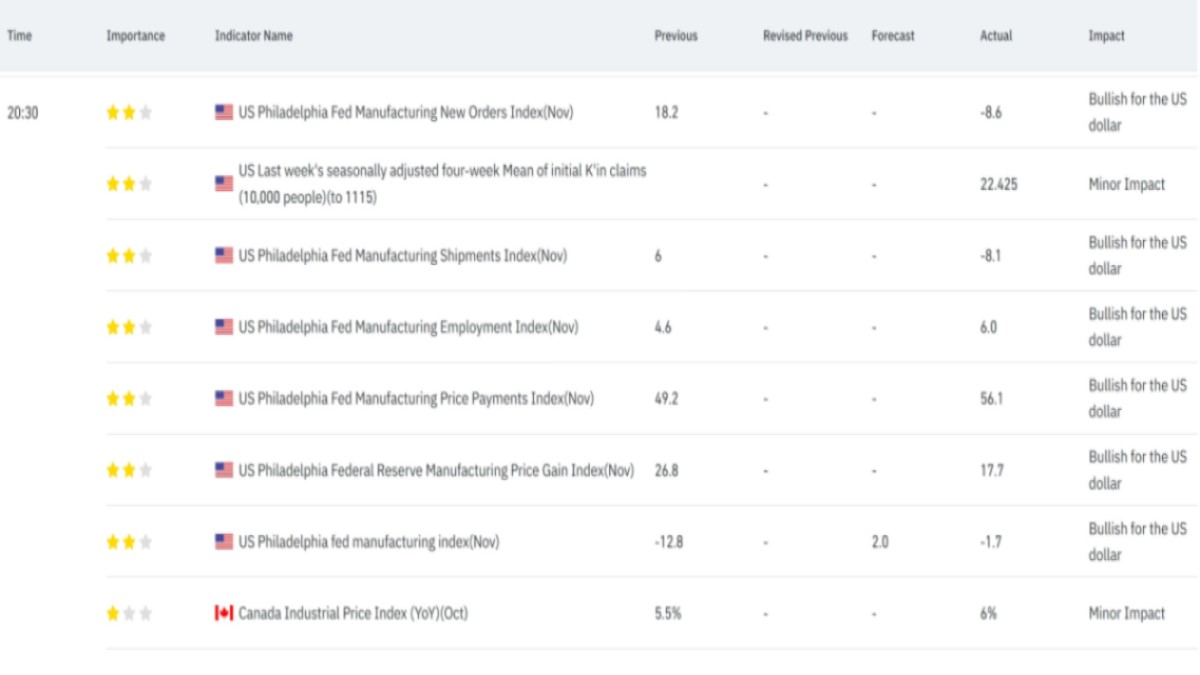

When geopolitical shocks hit, many people search for a moral interpretation. Markets, by contrast, search for a liquidity interpretation: “Does this change capital flows, hedging costs, or energy availability?” That’s why AP’s emphasis on tapping Venezuelan oil is more than color—it’s a transmission mechanism. Energy is a macro input that shapes inflation expectations, corporate margins, and policy reactions, so an oil-linked narrative can ripple far beyond a single region.

This is where “market reaction” becomes less about the event itself and more about second-order effects. A shock can push some participants toward safety (cash-like instruments, short duration, or metals) while simultaneously pushing others toward exposures that benefit when uncertainty rises (certain energy-linked risk premia). The educational point is not to assume one clean direction. It is to accept that the same headline can create different incentives across households, funds, and corporations with different liabilities and time horizons.

A useful way to stay grounded is to track three channels in parallel:

• Energy channel: does the event raise uncertainty around supply, sanctions, shipping routes, or production targets?

• Policy channel: do lawmakers, courts, or international bodies introduce new constraints that affect duration and outcomes?

• Funding channel: does risk-off behavior tighten financial conditions, widen spreads, or alter the demand for leverage?

Geopolitics moves markets fastest when it moves all three channels at once. That is why the first week can matter more than the first hour.

3) The ‘Multipolar World’ Lens: Useful Hypothesis, Not Prophecy

Commentators like Simon Dixon argue we’re moving toward a more multipolar order—power and capital spread across blocs and sovereign actors, with gradual pressure on dollar dominance over time. Agree or not, the lens is useful because it reframes the question. Instead of “is this the start of one catastrophic event,” it asks: “is this one episode inside a longer reallocation of power, trade, and capital?” That shift encourages scenario thinking rather than headline addiction.

But this lens can be misused. The risk is that “multipolar” becomes a catch-all explanation that erases nuance: every conflict is reinterpreted as inevitable, every price move becomes a sign of collapse, every policy decision becomes a plot. The opportunity is more practical: in a world with more competing centers of power, it becomes rational for countries and corporations to diversify dependencies—trade partners, payment rails, reserve assets, and supply chains. Even if the dollar remains central for years, the incentives to build redundancy can still intensify.

So treat the multipolar narrative the way you would treat a macro model. It can help you organize possibilities, but it should not replace evidence. The goal is not to predict a single outcome; it is to reduce surprise by acknowledging that more than one outcome is plausible.

4) Why ‘Hard Money’ Keeps Returning to the Stage

In periods of geopolitical uncertainty, people reach for assets that feel less negotiable. Gold has played that role for centuries. Bitcoin is newer, and it behaves very differently day to day, but it is increasingly discussed in the same sentence—not because it is identical to gold, but because it is designed to be politically neutral at the protocol level and globally transferable at the network level. In a world where payment access can be conditioned, scrutinized, or restricted, neutrality becomes a feature that people suddenly know how to price.

To be clear, “hard money” is not a magic shield. Gold can be volatile. Bitcoin can be dramatically more volatile. The educational point is different: when trust in the smooth functioning of cross-border systems declines, demand for neutral collateral and alternative settlement options often rises. That demand may express itself through metals, through certain currencies, through on-chain rails, or through a mix—depending on who is hedging and what they are allowed (or regulated) to hold.

If you want a clean, non-hyped way to think about it, focus on function rather than ideology:

• Settlement optionality: how easily can value move across jurisdictions if traditional rails slow down or fragment?

• Counterparty minimization: how much of your “asset” is a promise from someone else, and how enforceable is that promise in stress?

• Transparency vs. privacy trade-offs: which systems provide auditability, which provide discretion, and what are the compliance implications?

Hard money debates often become cultural. But in stressed environments, they are also operational.

5) The Hidden Market: Information Hygiene in the Age of Synthetic Media

One of the most underpriced risks in 2026 is that people still behave as if the information layer is stable. It isn’t. WIRED reported that after Trump’s announcement, disinformation spread quickly across major platforms, including recycled footage and AI-generated images and videos presented as “proof” of events. This is not merely embarrassing; it is destabilizing. When fake visuals accelerate emotional certainty, they can cause real financial decisions to be made faster than verification can catch up.

The result is a new kind of volatility premium: the premium attached to not knowing which “evidence” is real. In older eras, you might mistrust opinion. Now you must sometimes mistrust imagery itself. For crypto markets—where narratives already travel at high speed—this is especially relevant. A single viral clip can move positioning before anyone can confirm its origin, and by the time fact-checking arrives, the crowd may already be leaning the same way.

A simple checklist can help:

• Prefer primary reporting from major wires and established outlets over viral posts and screenshots.

• Treat “too clean” images and “perfectly cinematic” clips as suspicious until provenance is clear.

• Keep your own notes separated into “confirmed,” “reported,” and “unverified,” and don’t let them blur.

Information hygiene is not moral virtue. It is risk management.

Conclusion

If the first days of 2026 feel unusually volatile, it may be because volatility has expanded beyond price. We now have volatility in geopolitics, volatility in policy, and volatility in information itself. Reuters, AP, and CBS reporting about Trump’s claim of capturing Maduro and Flores is the kind of event that can reprice energy expectations and risk budgets quickly. But the more durable lesson is how to think: map channels, avoid early certainty, and treat narratives as hypotheses until evidence hardens them.

In that environment, it is unsurprising that “hard money”—gold, and increasingly Bitcoin—re-enters the conversation. Not as a promise of easy outcomes, but as a reminder that when systems are being renegotiated, neutrality and optionality become valuable traits. Whether the world is truly becoming multipolar is still a live question. What is not a question is that the era of single-story explanations is ending.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the capture of Maduro and his wife confirmed?

Major outlets reported that President Trump said Maduro and Flores were captured and removed from Venezuela following a U.S. operation. As with any fast-developing situation, operational details and independent confirmations can evolve; rely on updated reporting from established outlets rather than social-media summaries.

How do geopolitical shocks typically affect Bitcoin and gold?

Reactions vary. Some participants treat them as hedges, while others reduce exposure during risk-off episodes. The more useful approach is to watch the channels—energy pricing, funding conditions, and policy responses—which often influence cross-asset moves more than the headline alone.

What does ‘multipolar world’ mean in this context?

It generally refers to a world where power and capital are distributed across multiple blocs rather than concentrated in one dominant center. Commentators differ on how fast that shift is happening and what it implies. As a framework, it can help structure scenarios, but it should not replace evidence.

Why is disinformation a market issue, not just a media issue?

Because disinformation can accelerate emotional certainty and crowd positioning before verification is possible. That can create short-term volatility and longer-term mistrust, raising the noise-to-signal ratio for everyone.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. Geopolitical events can evolve quickly and reporting can change as more information becomes available. Consider consulting qualified professionals for guidance relevant to your circumstances.