‘We’ll Run Venezuela’ Meets Orinoco Reality: Why the Oil Plan Is Harder Than the Headline

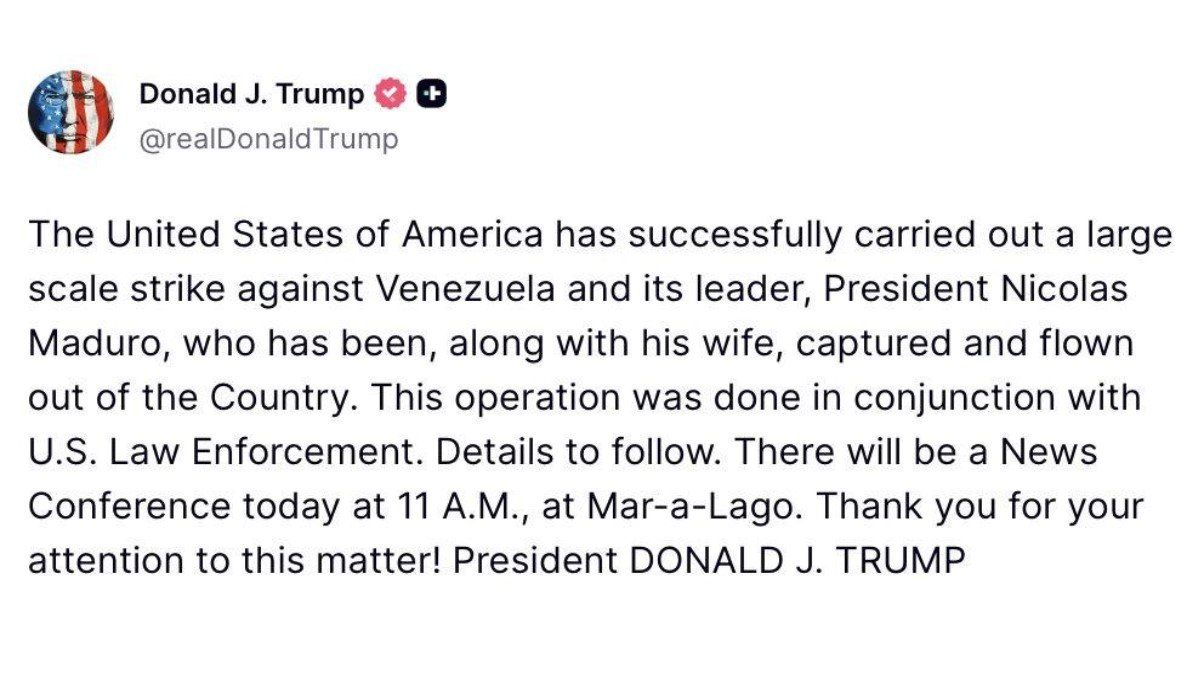

Headlines can be loud enough to trick us into thinking the world has already changed. Reporting on January 3, 2026 described President Donald Trump saying the U.S. carried out a military operation in Venezuela, captured President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores, and would temporarily “run” the country until an orderly transition. In the same breath, the story pivoted to oil: Trump said U.S. oil companies would invest billions to revive Venezuela’s industry and restart production.

It’s an explosive opening to the year—politically, economically, and psychologically. But if you want to understand what this could mean for markets, the useful skill is not outrage or celebration. It’s constraint-mapping. Venezuela’s oil is immense on paper. In practice, it’s one of the most technically and institutionally demanding hydrocarbon systems on Earth. That gap between reserve size and deliverable barrels is where most market misconceptions are born.

1) What was said—and why markets should treat it as a policy claim, not a finished outcome

According to AP’s reporting, Trump said the U.S. would “run” Venezuela at least temporarily, and that U.S. officials would oversee the country during a transition while tapping its oil to sell abroad. Reuters separately reported Trump’s comments that major U.S. oil firms would invest billions to restore deteriorated infrastructure and that Venezuela’s heavy crude is strategically important for certain U.S. refineries.

Those statements—if pursued—would imply a rare degree of direct U.S. involvement in the governance of a sovereign oil state, inviting legal scrutiny and international pushback. AP noted concerns about congressional authorization and international reaction. This matters because the oil market does not only price geology; it prices governance. If the governance pathway is contested, the “barrels-to-market” timeline stretches—and timelines are what move energy curves.

• Educational lens: treat the first 48 hours as a contest between narratives (“quick reboot”) and constraints (“complex rebuild”).

• Market lens: oil prices may respond to uncertainty first, then reprice on feasibility later.

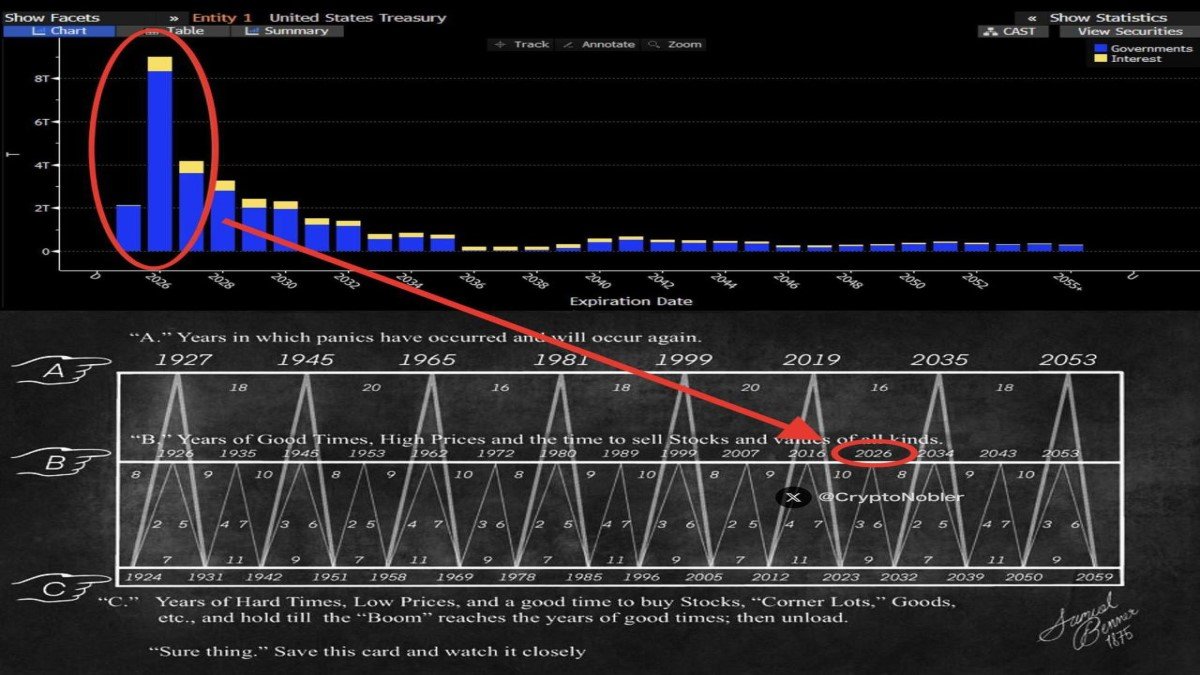

2) “303 billion barrels” is real—but it is not the same thing as fast supply

Venezuela does hold the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves—around 303 billion barrels—according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration and OPEC’s statistical tables. That number is often repeated as if it automatically implies near-term abundance. But reserves are a stock; production is a flow. Converting stock into flow requires functioning institutions, skilled labor, equipment, service companies, reliable power, secure logistics, and finance that can survive political risk.

EIA’s country analysis brief emphasizes that most of Venezuela’s proven reserves are extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco Belt. Extra-heavy oil is not a “turn the valve” resource. It tends to require advanced recovery techniques, blending/dilution, and processing capacity. So even if capital arrives, production ramps are measured in years, not weeks—especially after long underinvestment and sanctions constraints.

• Core idea: the reserve figure tells you the ceiling of potential, not the speed of delivery.

3) The Orinoco Belt problem: geology that demands institutions

Orinoco crude is heavy and technically demanding. That matters because the bottleneck is rarely “how much oil exists.” The bottleneck is “how reliably can it be produced, treated, transported, and sold.” EIA notes that extra-heavy extraction requires higher technical expertise—expertise international firms can provide, but participation has been constrained by sanctions and limited investment.

Reuters adds a second, market-facing detail: Venezuela’s heavy crude is valuable for specific U.S. Gulf Coast refineries that are configured for heavier grades. That creates a strategic logic for U.S. interest. But strategic logic doesn’t remove engineering reality. Heavy-oil systems depend on stable field operations, consistent diluent supply, and functioning upgrading/refining pathways. If any one link breaks, the “largest reserves” story turns into a “small export” reality.

• Translation for non-energy readers: Orinoco is less like a savings account and more like a complex factory. Factories don’t restart instantly after disruption.

4) “Billions” sounds big—until you compare it to the rebuild horizon

Trump’s message—U.S. companies will invest billions—sounds decisive. Reuters, however, highlights why professionals remain cautious: experts estimate rebuilding Venezuela’s oil industry could require at least a decade and tens of billions of dollars, given decaying infrastructure and operational risk. In oil, “billions” is often feasibility; “tens of billions” is scale.

Here is the uncomfortable but educational point: the capital number is only half the story. The other half is continuity. If governance is uncertain, contracts can’t be priced. If contracts can’t be priced, supply chains won’t commit. If supply chains won’t commit, production targets become political theater rather than operational plans. Markets will continuously arbitrate this gap—rewarding credible steps (security, permitting, services returning) and punishing ambiguity (legal disputes, sanctions confusion, local resistance).

• What to watch: service-company mobilization, spare parts flow, power-grid reliability, and credible export logistics—these are the real leading indicators.

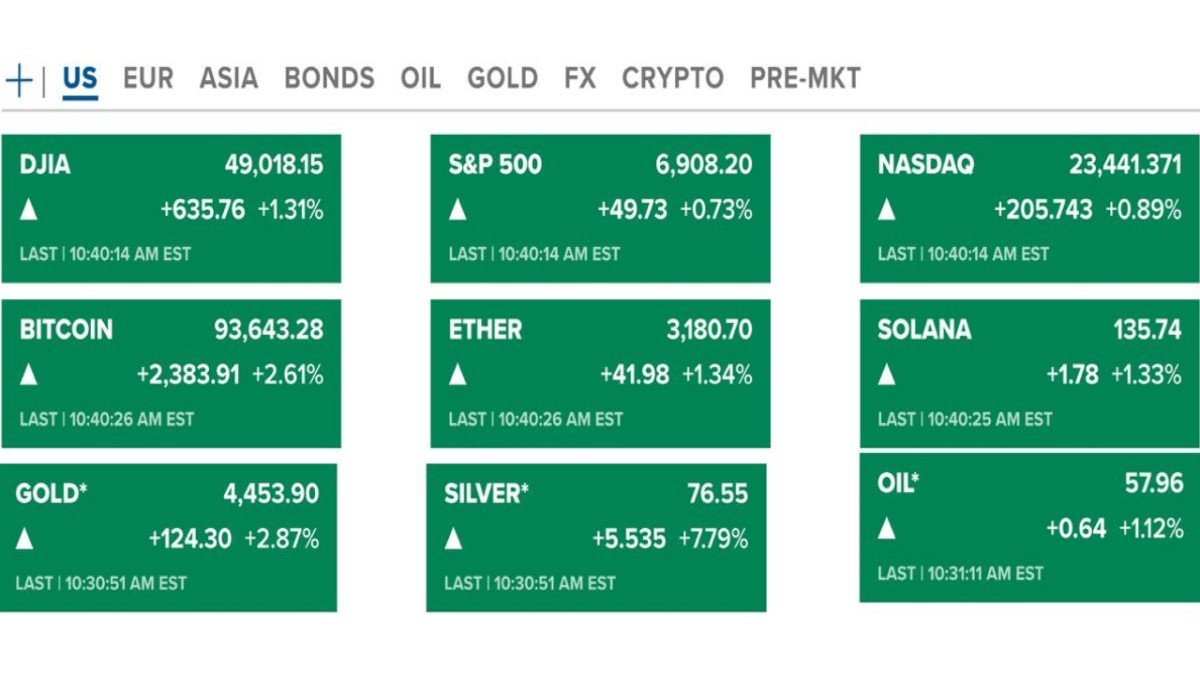

5) The market implications are second-order: inflation narratives, energy equities, and policy expectations

When a geopolitical event is framed as “we will unlock massive oil,” the market’s first instinct is to map it onto inflation. More oil supply eventually can soften certain price pressures, which can influence expectations about rates, consumer spending, and corporate margins. But the timing matters. If the supply path is slow, the near-term effect can be the opposite: uncertainty and disruption premiums that keep energy risk priced in.

This is why the biggest market move may not be crude itself. It could be the re-rating of energy producers and service companies (on expectations of capex), the repricing of emerging-market risk (on regional stability concerns), and the shifting of macro narratives about the dollar and reserves (on whether the world feels more fragmented). These are not one-day trades; they’re medium-horizon positioning themes.

• Educational warning: avoid “one headline, one trade.” Geopolitics moves through lags.

6) Why “hard money” (gold and Bitcoin) re-enters the conversation during shocks

In moments like this, people reach for assets that feel less dependent on political discretion. Gold is the traditional beneficiary of uncertainty hedging. Bitcoin is newer and more volatile, but it is increasingly discussed as an alternative reserve-like asset precisely because it is globally transferable and not issued by a single country. That doesn’t make it a guaranteed winner—volatility cuts both ways—but it explains why the narrative resurfaces whenever the geopolitical map looks less stable.

The brand-safe takeaway is functional, not ideological: uncertainty increases demand for optionality. Optionality can express itself through cash, short-duration instruments, metals, or digital assets, depending on constraints and preferences. In a multipolar-feeling world, diversification becomes a rational behavior—even if the dominant system remains dominant for a long time.

7) A practical checklist for reading fast-moving geopolitical headlines (without overreacting)

Events that mix military action, governance claims, and commodity resources produce rapid narrative inflation. The best defense is a structured reading approach. Start by separating verified reporting from political statements. Then ask: what must happen operationally for the headline thesis to become real?

Here is a compact, educational checklist you can reuse for future events:

• Authority: What legal basis is cited? Are there congressional or international reactions that could slow execution?

• Logistics: Can production actually ramp (equipment, power, workforce), or is it a multi-year rebuild?

• Finance: Who funds the capex and under what contract stability?

• Timing: Are we talking weeks (sentiment) or years (supply)?

Most market mistakes happen when people answer the “timing” question with emotion instead of engineering.

Conclusion

The claim that the U.S. will temporarily run Venezuela and that U.S. oil firms will invest billions to revive production is, on its face, a dramatic reordering of assumptions. Yet the oil market’s core truth remains stubborn: barrels are produced by systems, not slogans. Venezuela’s reserves are enormous, but much of that endowment lives in extra-heavy Orinoco crude that demands stable governance, specialized capability, and long-horizon capital.

So the analytical posture for 2026 is not “this changes everything immediately” or “this changes nothing.” It is: this creates a new set of constraints that markets will attempt to price—often clumsily—until implementation reveals what is real. In volatile moments, the highest-value skill is not prediction. It is patience with complexity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it confirmed that the U.S. will “run” Venezuela?

Major outlets reported Trump saying the U.S. would temporarily run Venezuela during a transition. Whether and how that translates into durable governance structures depends on legal, political, and international developments that can evolve quickly.

Why doesn’t “the world’s largest reserves” mean quick production growth?

Because reserves are a measure of oil in the ground; production depends on infrastructure, expertise, investment, and stable operating conditions. EIA notes much of Venezuela’s reserves are extra-heavy Orinoco crude, which is more complex and costly to develop than conventional oil.

Will U.S. oil companies investing “billions” rapidly increase supply?

Not necessarily. Reuters cites analysts warning that rebuilding Venezuela’s oil industry may require at least a decade and tens of billions in investment, reflecting the scale of deterioration and operational risk.

How should this affect a crypto reader?

Geopolitical shocks often revive discussions about neutral collateral and settlement optionality (gold and sometimes Bitcoin). The prudent approach is to treat that as a framework for understanding narratives—not as a promise of outcomes.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. Geopolitical events and reporting can evolve quickly as new information emerges.