Energy Choke Points in 2026: If Venezuela Becomes a Lever, What Markets Will Actually Price

In every geopolitical episode, two stories compete for attention. The first is the moral story—who is right, who is wrong, who violated what. The second is the mechanical story—what flows change, what costs move, what policies tighten, and which balance sheets suddenly look fragile. Financial markets, almost by design, prioritize the mechanical story. They may care about ethics as people, but they trade consequences as a system.

That distinction matters for the “energy confrontation” narrative circulating around early 2026: the idea that the United States, by shaping Venezuela’s trajectory, can reduce China’s access to discounted crude; and that China could respond by restricting exports of strategically important resources. Whether you agree with the framing or not, the market-relevant question is concrete: are we entering an era where energy and critical materials are treated like financial sanctions—tools of leverage rather than just commodities?

1) Venezuela isn’t “just oil”—it’s optionality plus infrastructure

It’s tempting to treat Venezuela as a single datapoint: “largest reserves.” But reserves are potential energy, not delivered energy. The difference between a barrel in the ground and a barrel in a refinery is an entire industrial universe: capital expenditure, skilled labor, maintenance cycles, upgrading capacity (especially for heavier grades), pipelines, ports, insurance, and predictable operating conditions.

So when markets hear talk of “control” or “access,” the serious interpretation is not immediate supply. It’s optionality: the probability that production can be stabilized, expanded, and routed through friendly channels over a multi-year horizon. Optionality is powerful because it changes the future distribution of oil balances, even if today’s physical flows barely move.

This is why oil can sometimes fall on headline tension: a market can price near-term risk while simultaneously pricing longer-term supply unlock. The first-order headline is conflict; the second-order trade is “future barrels may become more reachable.” Those can coexist.

2) The real battleground is the choke point, not the headline

The phrase “blocking China’s oil tap” is emotionally strong—but markets translate it into narrower variables. A choke point is any step in the chain where a small policy change can produce a large economic effect. In the energy world, choke points include shipping routes, insurance access, payment rails, spare parts, and refinery compatibility (heavy vs light crude constraints).

If Venezuela exports a large share of its crude to China in certain periods (numbers vary by dataset and time window), the direction of that flow matters less than the mechanism that enables it. When the mechanism is disrupted—through policy pressure, operational constraints, or contracting restrictions—buyers don’t just “lose oil.” They lose predictability, and predictability is what keeps inflation expectations anchored.

In macro terms, the fear is not a one-week spike in crude. The fear is a regime shift: energy becoming less of a market and more of a negotiating table.

3) “Resources-for-resources” retaliation: why materials matter as much as oil

If the retaliation channel shifts from oil to strategic materials—whether silver, specialty metals, or other inputs used in electronics, defense, solar, and industrial supply chains—the market impact can be surprisingly broad. Energy shocks raise costs directly. Materials shocks raise costs indirectly by slowing manufacturing throughput, delaying capex projects, and increasing the working-capital burden across supply chains.

Even rumors of export constraints can create precautionary stockpiling. That’s how physical tightness becomes financial tightness: companies hold more inventory, cash gets tied up, and credit conditions quietly worsen. This is where a commodity story can morph into a liquidity story—without a dramatic headline on your screen.

Importantly, this is also where policy responses appear. Governments don’t like supply-chain surprises. If markets sense that resource leverage is becoming normalized, investors start pricing a higher probability of industrial policy—subsidies, stockpiles, reshoring incentives, and strategic procurement. Those policies can support certain sectors while raising the baseline level of fiscal and inflation uncertainty.

4) The inflation channel: it’s not oil that breaks markets—it’s expectations

Oil is a visible price; inflation is a belief system. When energy becomes a bargaining chip, the market doesn’t only ask “what is crude today?” It asks “how stable is the energy input cost over the next 6–18 months?” That expectation influences wage bargaining, corporate pricing power, and central-bank reaction functions.

If the base case shifts from “energy is competitive” to “energy is political,” inflation risk premia can rise. And when inflation risk premia rise, long-duration assets (growth equities, long-dated bonds, and some segments of crypto that behave like high-beta tech) can become more sensitive—even if earnings are fine.

That’s why the key macro variable to watch is often not spot crude—it’s the behavior of yields and breakevens. Markets fear a world where inflation is not just cyclical, but strategically manufactured.

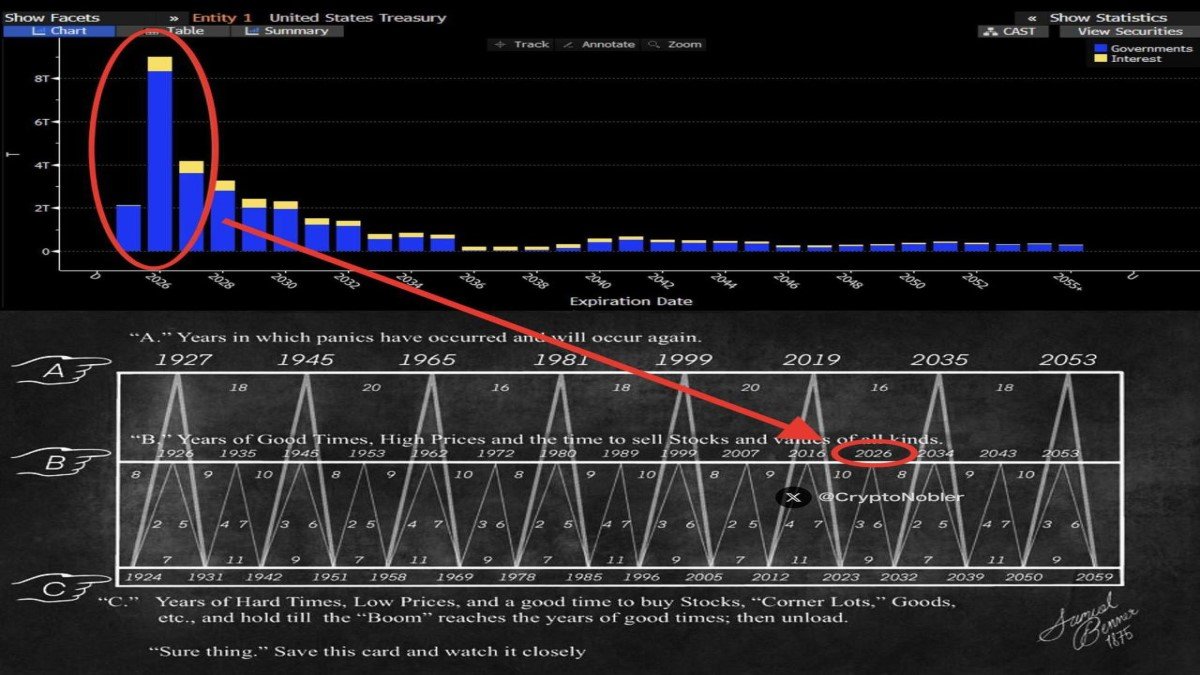

5) The Treasury maturity problem: why timing matters in 2026

The top half of the image references a Treasury maturity profile—often used to highlight periods where refinancing needs concentrate. The exact distribution changes with issuance decisions, but the concept is stable: when large amounts of debt roll over in a short window, the system becomes more sensitive to rates and term premium.

Now connect the dots. If energy tension increases inflation uncertainty, yields can remain sticky or risk moving higher. Higher yields tighten financial conditions. Tighter conditions reduce liquidity. Reduced liquidity is where cross-asset “surprises” come from: you can have stable equities on the surface while the plumbing underneath gets strained.

This is also why geopolitical energy stories can matter for crypto, even when nothing “crypto-specific” happens. Crypto is often a liquidity asset: it performs best when marginal liquidity is expanding and risk appetite is stable. When liquidity gets squeezed, even strong narratives can temporarily lose to funding reality.

6) Stocks, oil, and Bitcoin: why the short term and long term can disagree

It’s common to hear: “Oil up, stocks down, Bitcoin down.” That’s a neat story—and sometimes it’s wrong. The market response depends on which layer dominates: supply unlock vs supply disruption; inflation fear vs growth optimism; and above all, liquidity.

Here is a more realistic way to think about it:

• Oil: can drop on “unlock” expectations or rise on “disruption” fear. The direction is less important than volatility and the signal it sends about uncertainty.

• Equities: can remain resilient if markets interpret the event as contained or even growth-supportive (capex, infrastructure, defense, energy services). But equity leadership may rotate: energy and industrial beneficiaries can outperform while rate-sensitive growth lags.

• Bitcoin: can be pressured in the short term if liquidity tightens or if leveraged positioning is forced to unwind. Yet in the longer term, Bitcoin can reassert itself as a hedge narrative when the world appears more fragmented—particularly if participants perceive currency blocs and settlement constraints as rising structural features.

That last point needs careful wording. A “hedge” is not a guarantee. It’s a role that markets sometimes assign. Bitcoin can behave like a risk asset for months and then behave like an alternative reserve narrative during specific macro regimes. The relationship is conditional, not permanent.

7) What to watch next: the signals that separate story from structure

If you want to stay educational and grounded, ignore the loudest predictions and watch the tradeable signals. Structural shifts leave footprints.

• Energy spreads and refinery indicators: do heavy/light differentials and refining margins start moving in ways that suggest real constraints or real unlocking?

• Policy mechanics: do we see durable legal/contracting changes that alter who can buy, ship, insure, and finance flows?

• Materials pricing and lead times: do industrial input prices and delivery times signal bottlenecks beyond normal volatility?

• Rates and term premium: do longer-dated yields rise on inflation uncertainty rather than growth optimism?

• Liquidity stress markers: are there signs of forced deleveraging (sudden liquidations, widening credit spreads, or volatile FX funding)?

When these signals line up, the “energy war” narrative becomes less of a social-media phrase and more of a macro regime. Until then, it remains a scenario—a plausible one, but still a scenario.

Conclusion

The most useful way to interpret a potential US–Venezuela–China resource confrontation is not as a single bet on oil. It’s as a lens on choke points. When commodities become leverage, markets reprice uncertainty through inflation expectations, rates, and liquidity—often faster than they reprice the physical barrels themselves.

In the near term, that can mean volatility: equities rotating rather than collapsing, commodities swinging on narrative shifts, and Bitcoin reacting to liquidity conditions even if its long-run story feels intact. Over the longer arc, if the world moves toward a more multipolar, resource-leveraged structure, “neutral” assets—whether gold or Bitcoin—may gain strategic relevance as portfolio components. But that relevance is not a promise of constant outperformance. It’s a recognition that the definition of risk is changing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is it realistic to say the US can fully “block” China’s oil access?

In most cases, “block” is too absolute. Markets think in terms of friction: higher costs, less predictability, and constrained routing options. Even partial friction can change inflation expectations and risk premia.

Why would materials restrictions matter so much?

Because manufacturing systems are sensitive to small bottlenecks. If key inputs become less available or more expensive, companies can face delays, higher working-capital needs, and margin pressure—effects that propagate into growth and credit conditions.

Why could Bitcoin fall in the short term but be viewed as useful long term?

Bitcoin often responds to liquidity in the short term (especially when leverage is present). Over longer horizons, it can be viewed as an alternative reserve-like asset in regimes where monetary and geopolitical fragmentation rises. Neither behavior is guaranteed; both are conditional.

What single indicator best captures whether this is becoming structural?

Watch the rates/term-premium response. If inflation uncertainty drives yields higher while liquidity tightens, cross-asset volatility tends to persist. That’s when geopolitics starts behaving like macro, not just news.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. Geopolitical narratives can be incomplete or evolve quickly, and market reactions may reflect positioning and liquidity as much as fundamentals. Always verify information using multiple credible sources and consider your own risk tolerance.