Venezuela’s Quiet Treasure: Why 161 Tons of Gold Matters More Than the Oil Headlines

When Venezuela enters the global conversation, the script is almost automatic: barrels, pipelines, sanctions, refineries, and the price of crude. Oil is the loud asset. It moves markets in real time, it has visible chokepoints, and it comes with daily scoreboard numbers that make for easy headlines.

But Venezuela also holds a quieter asset that behaves less like a commodity and more like a balance-sheet lever: gold. Unlike oil, gold doesn’t need a decade-long rehabilitation plan to become financially relevant. It can be pledged, moved, or used as credibility in negotiations—sometimes faster than politics can catch up.

This article is not about predicting outcomes. It’s about upgrading the mental model. If you want to understand why certain countries become “strategic,” you need to track not just what they can produce, but what they can collateralize—especially in a world where access to banking rails is increasingly conditional.

The number hiding in plain sight: 161 tons is not a headline, it’s collateral

Gold reserves are often treated like a trivia fact—something you learn about central banks and then forget. That’s a mistake. In periods of legal uncertainty, sanctions risk, or currency stress, reserve assets start behaving like negotiating instruments, not just savings accounts. They matter not because they are flashy, but because they are usable under constraints.

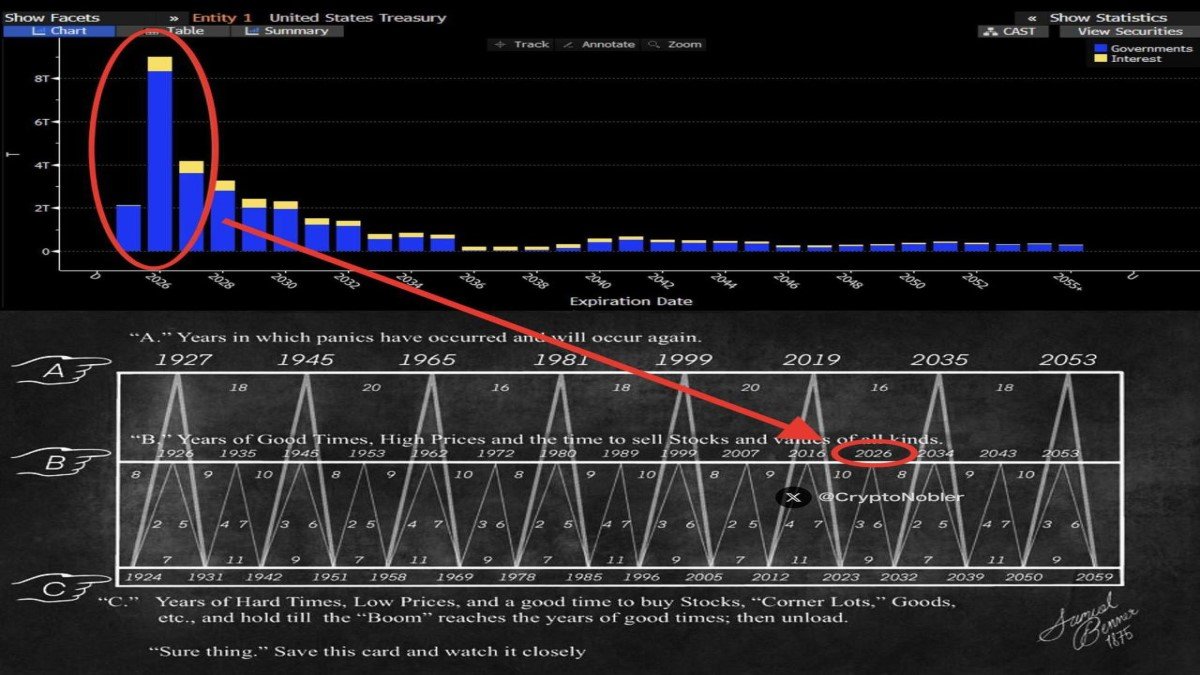

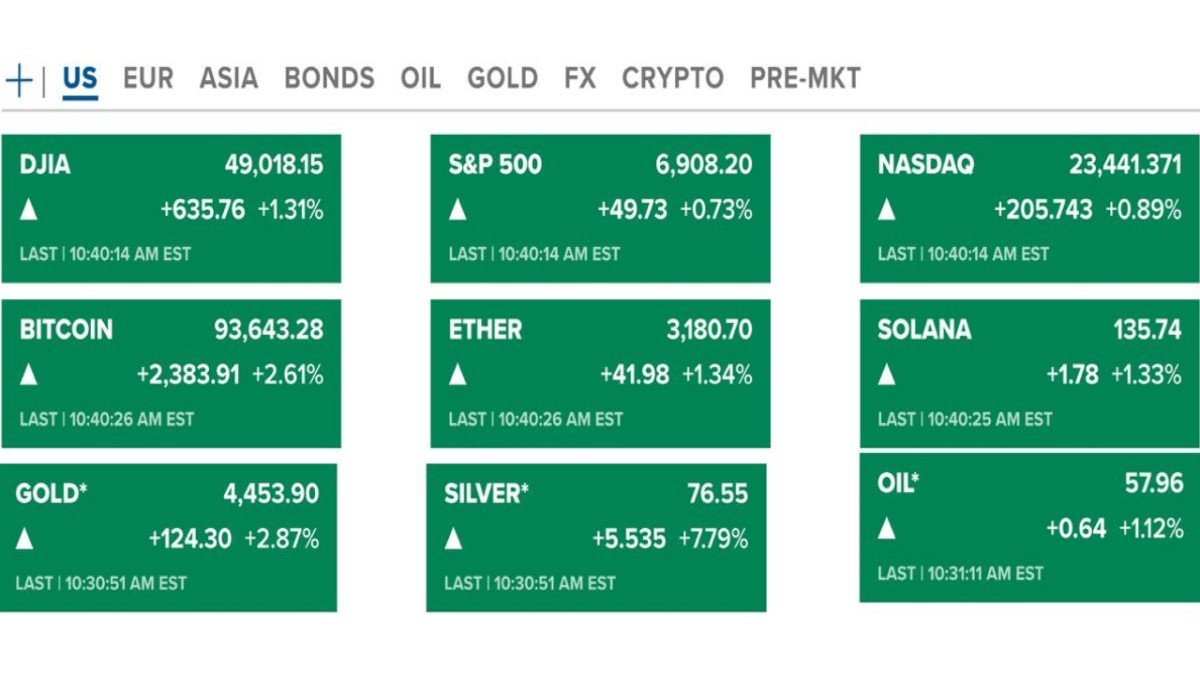

Venezuela is reported at roughly 161.2 tonnes of official gold holdings. Converted into troy ounces, that’s about 5.18 million ounces. At a hypothetical price level of $4,300/oz, the headline valuation lands around $22.3 billion. The more important insight is the sensitivity: every $100 move in gold adds roughly $518 million in mark-to-market value—without drilling a single well.

Here’s the simplest way to hold this in your head: oil is revenue if and only if you can produce and ship it; gold is value the moment you can legally access it.

Three implications follow—each easy to miss if you only watch oil:

• Gold is instant collateral: it can support credit lines, swaps, or liquidity arrangements faster than long-cycle commodities can.

• Gold is politically legible: it’s a familiar reserve asset to central banks and ministries, which reduces “translation costs” in negotiations.

• Gold is a jurisdiction story: where it sits (and who recognizes whom) can matter as much as how much exists.

One more nuance: Venezuela’s reported holdings are large relative to many peers in the region. On the same official-holdings table, Brazil is listed at 129.7 tonnes and Mexico at 120.3 tonnes. If you’re thinking in Latin American terms, Venezuela’s gold is not a footnote—it’s a regional outlier.

The market consequence is subtle: in high-stress moments, gold can become a short-cut to macro relevance. It’s a “portable balance sheet” in a way oil can’t be, because oil’s value is trapped behind infrastructure and time.

Oil is a project; gold is an instrument

It’s tempting to look at Venezuela’s oil reserves—often cited at about 303 billion barrels—and assume the economics are straightforward: control the resource, capture the wealth. That’s the kind of arithmetic people do when they confuse reserves with cash flow. Reserves are potential. Cash flow is a functioning industrial system.

Most of Venezuela’s resource base is extra-heavy crude, concentrated in the Orinoco Belt. Heavy oil is not simply “more oil.” It usually requires more technical input, more upgrading, different refinery configurations, and often sells at a discount relative to lighter grades. In plain English: even if the reserve number is huge, the path from ground to dollars is neither quick nor cheap.

A useful way to compare oil and gold is to look at their time-to-finance:

• Gold: once access is legally clear, it can be mobilized quickly as collateral, liquidity, or reserves.

• Oil: even with policy changes, production recovery tends to be slow; infrastructure rehab, skilled labor, capital, and contracting confidence take time.

• Oil (heavy crude): the “time penalty” grows because technology and upgrading capacity become bottlenecks, not accessories.

That’s why large numbers around “hundreds of billions in benefits” should be treated like marketing, not accounting. Even optimistic scenarios must price in: rehabilitation timelines, contract stability, debt and legal claims, and the reality that commodity wealth is often captured by the slowest moving part of the chain—permitting, logistics, or politics.

In other words, oil wealth is not merely extracted; it is organized. Gold wealth is not merely stored; it is recognized. Those verbs matter.

The custody problem: you can’t monetize what you can’t access

Gold has a unique weakness that oil doesn’t: custody can be geographically and legally fragmented. A barrel of oil under your soil is unambiguously yours in a geological sense. A bar of gold in a foreign vault is yours only to the extent that courts, recognition, and compliance frameworks agree you can touch it.

This is where Venezuela becomes a case study for modern financial sovereignty. The UK government has publicly documented a Supreme Court dispute over rights of access to Venezuelan gold held by the Bank of England, reflecting how recognition and governance claims can directly affect reserve usability. The lesson is not “gold is risky.” The lesson is that gold becomes a chess piece when politics challenges who the “state” is.

Think of this as the difference between ownership and operational control:

• Ownership is what balance sheets claim.

• Operational control is what legal systems and custodians enforce.

• Market value matters only when operational control exists.

That is also why the “gold lever” can show up in negotiations without a single announcement. If access becomes clearer (through recognition, settlements, or policy shifts), the same tonnage can suddenly behave like a newly unlocked credit facility. If access becomes murkier, the gold can remain economically inert despite being physically real.

This custody dynamic is one reason gold remains attractive to central banks during periods of geopolitical uncertainty—ironically including uncertainty about the system that stores it. The asset is non-sovereign, but the vault is not. That tension is not a bug; it’s the feature that forces countries to think strategically.

Why gold keeps winning mindshare: reserve assets are back in fashion

Gold’s resurgence is not purely about price. It’s about the return of settlement anxiety—the idea that access to global finance can be shaped by policy. The World Gold Council’s 2025 survey highlights that central banks have accumulated over 1,000 tonnes of gold in each of the last three years, and many reserve managers expect further increases. That is not retail FOMO; it’s institutional behavior responding to a more conditional world.

At the same time, gold has periodically traded above $4,300/oz in late 2025, reinforcing the idea that it is being repriced as a strategic asset rather than a sleepy hedge. Whether prices stay elevated is not the point here. The point is that the market is signaling demand for “assets that don’t need permission”—and gold is the oldest member of that category.

This is also where crypto quietly enters the conversation—not as a replacement, but as a parallel. When people talk about Bitcoin as “hard money,” they are often describing the same desire gold satisfies: portability, censorship resistance (in the broad sense), and independence from any single issuer.

But the more interesting bridge is tokenization. Tokenized gold products exist because markets want gold exposure that is more mobile than vault receipts. In a world where capital crosses borders at the speed of software, the question becomes: can reserve assets become programmable without becoming fragile? That’s not a hype question; it’s a design question about custody, transparency, and settlement finality.

For Venezuela specifically, this matters because any narrative about “resource value” will increasingly include the financial rails that convert value into usable liquidity. Oil needs ships and refineries. Gold needs custody and legitimacy. Tokenization needs compliance and robust settlement. Different rails, same theme: value is only as useful as the system that lets you move it.

A framework for reading the next Venezuela headline without getting hypnotized

When headlines focus on oil, it’s easy to treat everything else as background. But strategic outcomes often hinge on the quiet variables: what can be financed, what can be collateralized, what can be legally accessed, and what can be integrated into global settlement systems without triggering compliance alarms.

If you want a practical way to evaluate new developments, try this four-part lens. It’s less exciting than hot takes, but it survives contact with reality.

1) Accessibility: Is the asset usable, or merely existing? For gold, this means custody and recognition. For oil, it means operating capacity and export routes.

2) Time-to-value: How quickly can the asset change the financial position of the state? Gold can shift the story faster than oil because it doesn’t require industrial ramp-up.

3) Counterparty comfort: Who is willing to engage? Central banks and institutions have a long playbook for gold. Oil deals require long-lived trust in contracts, maintenance, and governance.

4) Downstream rails: What system turns the asset into transactions? For oil, it’s trade finance, shipping, refining. For gold, it’s vaulting, swaps, and reserve accounting. For tokenized forms, it’s compliance-grade settlement networks.

Once you use this lens, the “hundreds of billions” claims start to look less like destiny and more like a worksheet full of assumptions. That’s the healthy posture. Strategic assets don’t automatically produce prosperity; they create bargaining power and optionality—if governance and systems can convert them into durable outcomes.

Conclusion

Oil will keep dominating the Venezuela narrative because oil moves headlines. But gold moves balance sheets—and in a world of sanctions risk, legal complexity, and shifting settlement norms, balance sheets can be the deeper battlefield.

Venezuela’s reported 161.2 tonnes of gold is not just a statistic. It’s a reminder that “resource wealth” is not one thing. Some wealth is industrial and slow (oil). Some wealth is financial and fast (gold). And increasingly, the most strategic advantage comes from understanding how these forms of wealth plug into global rails—legal, institutional, and sometimes digital.

If you’re trying to interpret macro narratives—whether you’re watching commodities, currencies, or crypto—the best habit is to ask one question before anything else: Is this asset value, or is it usable value? The difference is where the real story lives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is 161 tons of gold “a lot” in global terms?

Globally, the largest holders are far above that level. But within Latin America, it is meaningfully high compared with other major economies in the region. The more important point is not the rank; it’s that reserve gold can act as collateral when access is clear.

Does higher gold price automatically help a country like Venezuela?

Higher prices raise the mark-to-market value of holdings, but the practical benefit depends on whether the country can legally and operationally access and mobilize the gold. Custody location and recognition dynamics can be decisive.

Why can’t oil reserves be treated like a financial reserve?

Oil reserves are potential energy in the ground. Turning them into financial value requires production, infrastructure, contracts, and time—especially when the reserves are extra-heavy crude that is technically and financially demanding to monetize.

How does this connect to crypto without turning into hype?

The connection is conceptual: markets are repricing “permission-light” assets and experimenting with programmable representations (like tokenized gold). The key questions are custody, compliance, and settlement integrity—not price predictions.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or investment advice. Digital assets and commodities can be volatile, and readers should evaluate risks carefully and consult qualified professionals where appropriate.