When Self-Custody Meets Software Risk: Lessons From Trust Wallet’s Christmas Security Incident

For years, the most repeated mantra in crypto has been simple: not your keys, not your coins. Self-custody wallets became the symbol of independence from centralised platforms, promising users full control over their assets. But the Christmas-time security incident involving Trust Wallet's browser extension shows that holding your own keys is only part of the story. If the software that handles those keys is compromised, control can still be lost.

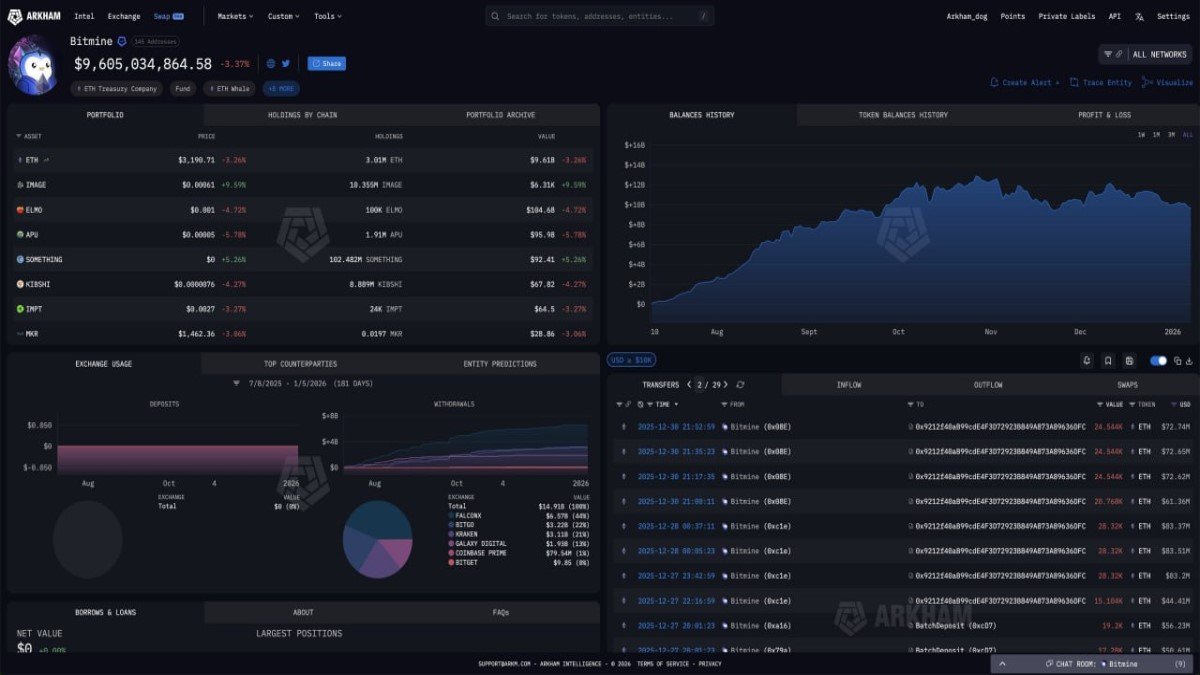

In late December, a specific version of the Trust Wallet browser extension (v2.68) was found to contain a deliberate security backdoor. The issue primarily affected desktop users and led to an estimated 7 million USD in losses. Security firm SlowMist reported that the malicious code had been prepared from 8 December, added to the extension on 22 December, and then used to drain funds on Christmas Day. On top of that, the code reportedly collected personal data from affected users and sent it to a remote server controlled by the malicious party.

On the corporate side, the response was immediate and significant. Changpeng Zhao (CZ), co-founder of Binance, which owns Trust Wallet, publicly confirmed that Binance would cover the full losses suffered by users. Trust Wallet urged everyone to upgrade to version 2.89 of the extension, and recommended affected users to check their machines for malware and follow reimbursement guidance.

What makes this incident particularly unsettling is that several experts, including on-chain investigator ZachXBT and commentators such as Anndy Lian, believe it was likely an insider-driven compromise. The malicious build was apparently distributed through official channels, implying that someone with privileged access to the release pipeline or website was involved. In parallel, data from Chainalysis suggests a worrying trend: if one excludes a large single exchange case at Bybit, personal wallets account for roughly 37% of the total value taken in 2025. In other words, non-custodial setups are increasingly in the firing line.

This article does not aim to dramatise the event, but to unpack what it really means for self-custody, wallet design and user behaviour going forward. The central question is not whether self-custody is "good" or "bad", but what kind of risk model users are actually signing up for.

1. What Actually Happened: A Short Timeline

Based on public information so far, the sequence of events can be summarised as follows:

• Early December: According to SlowMist, the malicious party begins preparing the infrastructure for the operation around 8 December, including servers to receive data and code tailored to the Trust Wallet extension.

• 22 December: A version of the Trust Wallet browser extension (v2.68) is pushed that contains a backdoor. From a user's point of view, this looks like a normal update; most people installing or auto-updating the extension would not notice anything unusual.

• Christmas Day: The malicious code is triggered. It is used to sign or relay unauthorised transactions from affected wallets, leading to around 7 million USD in cumulative losses. At the same time, the code reportedly collects personal data and sends it to a remote server.

• After the incident: Security researchers and on-chain analysts begin tracing the flows. Hundreds of users are identified as affected. Trust Wallet releases guidance and a new version (v2.89) and urges users to update. CZ confirms that Binance will reimburse all verified victims.

The pattern fits what many would describe as a supply-chain style compromise rather than a direct assault on blockchain protocols. The base networks (Bitcoin, Ethereum and others) did not fail. Instead, the issue was at the application layer: a widely used wallet extension on desktop devices was distributing code that did not act in the user's interest.

2. Why Browser Extensions Are A High-Risk Interface

To understand why this matters so much, it helps to look at the role browser extensions play in the crypto stack. Extensions such as Trust Wallet's desktop add-on or other web-based wallets are designed to sit between your browser and the blockchain. Their responsibilities typically include:

- Storing or accessing private keys or key material (sometimes within the browser, sometimes via external devices).

- Displaying transaction details in a human-readable way before the user signs.

- Injecting wallet objects into web pages so that decentralised applications (dApps) can request signatures.

- Managing network settings, token lists and permissions for different sites.

Because extensions live inside the browser environment, they inherit both its strengths and weaknesses. On the one hand, they are convenient and easy to install, lowering the barrier to entry. On the other, they are exposed to several categories of risk:

• Update trust. Users often rely on automatic updates from extension stores or official websites. If the update pipeline is compromised, people download harmful code without any manual action.

• Permission sprawl. Extensions need broad permissions to function correctly. If those permissions are misused, the software can see or alter far more data than a typical webpage.

• Blending of environments. Browsers are where people click links, open emails, visit new projects and interact with embedded content. It is extremely difficult for non-expert users to distinguish safe from unsafe interactions in real time.

Put simply, a browser extension that can sign transactions on your behalf is one of the most sensitive pieces of software on your machine. If its code is modified in a malicious way, "self-custody" can quickly become an illusion: you still hold the key, but the software is deciding how that key is used.

3. The Insider And Supply-Chain Dimension

The most disturbing aspect of the Trust Wallet case is the suspicion that an insider or a party with insider-level access was involved. According to several analysts, including ZachXBT and Anndy Lian, the malicious extension build appears to have been distributed through the normal, trusted channels. That suggests that the adversary was not simply tricking users into installing a fake lookalike, but was able to push code into the official release path.

From a security-governance perspective, this raises difficult questions:

• Who can push production builds? Healthy engineering organisations enforce separation of duties: one person should not be able to write code, approve it, build it and publish it without oversight.

• Are builds reproducible? In a reproducible-build setup, independent parties can take the published source code, compile it and verify that the resulting binary matches what users download. If those checks are missing, it is much easier for malicious changes to slip through.

• How are signing keys managed? If extension or installer signing keys are not stored securely (for example in dedicated hardware modules), they become attractive targets. Whoever controls the signing key controls what looks "official" to users.

Insider risk is uncomfortable to talk about because it cannot be solved with cryptography alone. It is about processes, incentives and culture. The Trust Wallet incident is a reminder that even technically sound cryptography can be undermined by weaknesses in the human and organisational layers.

4. Self-Custody Versus Reality: What The 37% Figure Tells Us

Chainalysis estimates that if one removes a large single event involving Bybit, around 37% of the value taken in 2025 has come from personal wallets. That number is striking because it challenges a popular assumption: that leaving funds on exchanges is risky, while self-custody automatically confers safety.

In reality, what self-custody does is change the type of risk, not remove it:

- On centralised platforms, the main concerns are platform failure, mismanagement or legal action.

- In self-custody, the main concerns are key management, device security and the integrity of the wallet software itself.

The Trust Wallet incident falls squarely into the second category. Users who believed they were avoiding institutional risk by holding their own keys instead found themselves exposed to software and supply-chain risk. The fact that Binance has stepped in to cover losses is positive for affected individuals, but it also blurs the line between custodial and non-custodial worlds: a centralised entity is effectively acting as an insurer of last resort for a self-custody product.

Over the long term, this trend may continue. As more large organisations sponsor or acquire wallet projects, the expectation may grow that major incidents will be compensated, even if the product is technically non-custodial. That can be reassuring, but it also introduces a subtle moral hazard: if users believe they will always be made whole, they may be less motivated to adopt strict security practices.

5. Binance’s Response: Damage Control And Precedent

From a market-structure angle, Binance's decision to cover the roughly 7 million USD in losses has several important implications:

• Short-term trust repair. For affected users, the most urgent concern is whether they will recover their funds. A clear public commitment from CZ and Binance goes a long way towards preventing panic and reputational collapse.

• Signal to regulators. Authorities that worry about consumer protection often ask who bears responsibility in decentralised systems. Binance's response indicates that large brands are willing to take financial responsibility for products under their umbrella, even when these products are technically non-custodial.

• Precedent for the industry. Other wallet providers and exchange-linked products may now be judged against this standard. If a similar incident occurs elsewhere and users are not compensated, comparisons will be inevitable.

However, it is important to separate reimbursement from root-cause resolution. Covering losses addresses the immediate pain but does not, by itself, eliminate the conditions that allowed the incident to happen. The deeper work is less visible: rebuilding the release pipeline, tightening internal controls, and subjecting the entire build process to independent review.

6. Practical Lessons For Everyday Users

While the details of this case are specific to Trust Wallet's browser extension, the lessons apply far more widely. For ordinary users trying to navigate an increasingly complex ecosystem, several practical principles stand out.

6.1 Treat browser wallets as "hot" by default

Anything running in a general-purpose browser environment should be considered highly exposed. That does not mean it is unusable, but it suggests a clear separation of roles:

- Use browser extensions for small day-to-day balances, interacting with dApps, payments and experiments.

- Keep long-term holdings in more isolated setups, such as hardware wallets or dedicated devices not used for everyday browsing.

6.2 Diversify your wallet stack

Just as investors diversify assets, it often makes sense to diversify how those assets are stored:

- A browser-based wallet for frequent interactions.

- A mobile wallet on a device you control carefully.

- A hardware wallet or other cold-storage solution for larger balances.

This way, a single incident affecting one application or device does not automatically compromise your entire portfolio.

6.3 Watch updates carefully

Automatic updates are convenient, but they also create a single point where trust is concentrated. Some suggestions:

- Enable updates, but pay attention to unusual behaviour immediately after major version changes: unexpected prompts, altered interfaces, or repeated requests for permissions.

- Follow official communication channels (website, verified social accounts, support pages) for timely security advisories.

- When a serious issue is disclosed, prioritise action: update, move funds if advised, and review connected devices.

6.4 Strengthen your device hygiene

Even the best wallet software cannot fully protect you if the underlying device is compromised. Basic, but important steps include:

- Keep your operating system and browser up to date.

- Limit the number of extensions installed; remove anything you do not actively use.

- Run reputable security tools to scan for malware, especially after a known incident.

- Avoid installing software from unknown sources or following unsolicited download links.

6.5 Follow official remediation and reimbursement steps

In incidents like the Trust Wallet case, legitimate compensation usually involves:

- Announcements on official domains and verified channels.

- Clear, step-by-step instructions on how to verify your case and claim reimbursement.

- Minimal sharing of sensitive information; reputable providers will not ask for your seed phrase or full private keys under any circumstances.

If you are a Trust Wallet user, the immediate priorities are to ensure you are on the latest extension version, move funds to fresh addresses if you used v2.68, scan your computer, and follow updates from Trust Wallet and Binance regarding the reimbursement process.

7. What This Means For Developers And The Ecosystem

For teams building wallets and other key management tools, the Trust Wallet episode is a serious warning that user trust is no longer only about cryptography or user interface. It is equally about:

- Supply-chain integrity: reproducible builds, independent verification, and strict control over signing keys and release channels.

- Internal governance: role separation, code review procedures, whistleblower paths and robust logging to detect unusual activity in build systems.

- Transparency: timely and detailed post-incident reports, so that users and auditors can understand what went wrong and what has changed.

As more wallets are acquired or backed by large companies, there is also a growing expectation that governance and security standards should match those of regulated financial institutions. That does not mean abandoning open-source principles; in fact, open and verifiable code can be a strong asset. But it does mean that "move fast and break things" is no longer an acceptable approach for software that directly controls billions of dollars in user funds.

8. Conclusion: Self-Custody In A World Of Shared Responsibility

The Trust Wallet Christmas incident is unsettling precisely because it sits at the intersection of several powerful narratives. It challenges the comforting idea that self-custody alone is enough to guarantee safety. It illustrates the growing importance of software supply chains and insider risk. And it shows that, in practice, large centralised actors like Binance are still expected to step in when something goes badly wrong, even in ostensibly decentralised contexts.

None of this means that self-custody is a mistake. It does mean that self-custody must be understood as a practice, not a product. It is not simply about installing a wallet and writing down a seed phrase; it is about managing devices, scrutinising updates, diversifying storage methods and choosing providers that demonstrate mature security governance.

For users, the path forward is not to abandon non-custodial tools, but to use them with clear eyes: recognising both their strengths and their limits. For builders, the message is even sharper: as digital assets become part of mainstream portfolios, the expectations placed on wallet security, process integrity and post-incident accountability will only increase.

If there is a positive takeaway from this episode, it is that the ecosystem is gradually developing mechanisms of shared responsibility. Users are learning to ask harder questions. Developers are being pushed towards higher standards. And large platforms are beginning to act more like insurers and stewards rather than just venues for trading. In the long run, that mix of independence, scrutiny and support may be exactly what is needed for self-custody to fulfil its original promise.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and analytical purposes only and does not constitute investment, legal or security advice. Digital assets carry significant risk, including potential loss of principal. Always conduct your own research and consider consulting qualified professionals before making financial decisions or changing your security setup.