Mortgage Rates Drop After a $200B MBS Bid — The Hidden Mechanics Behind the Headline

U.S. mortgage rates can move for many reasons: inflation expectations, bond volatility, bank balance sheets, and the Federal Reserve’s stance. But sometimes they move for a simpler (and more revealing) reason: someone with a very large balance sheet decides to become the marginal buyer of mortgage risk.

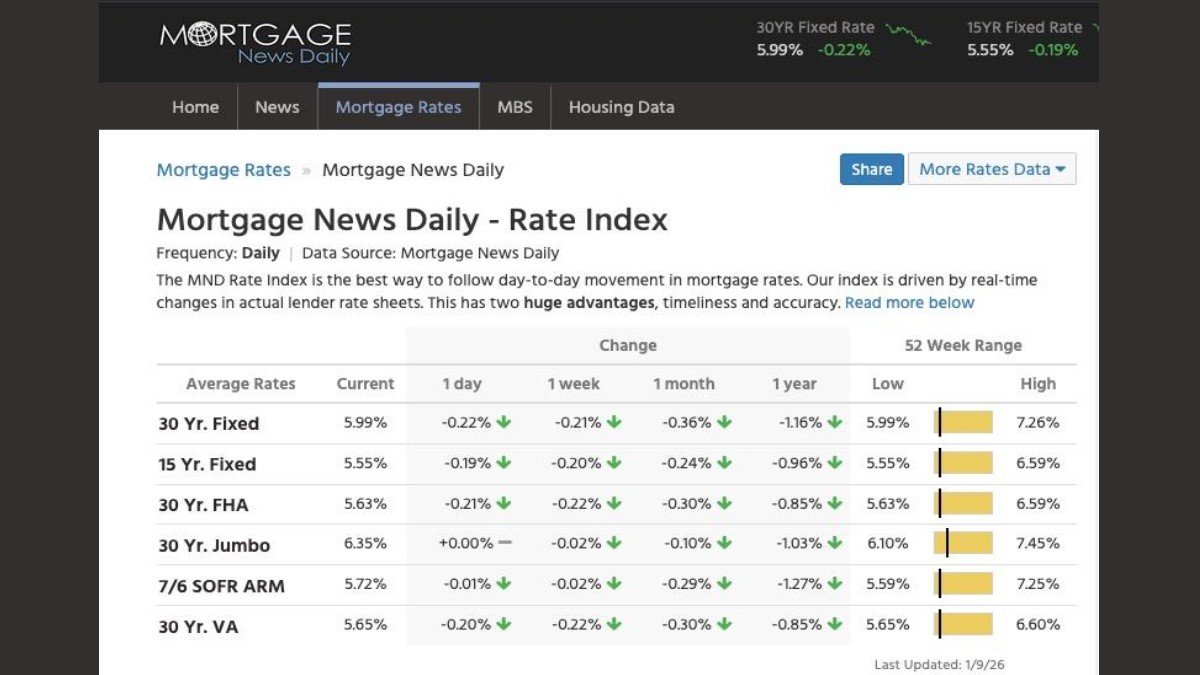

After reports that President Trump is directing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to purchase $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the Mortgage News Daily rate index showed the 30-year fixed rate falling to around 5.99% (with other categories down as well). The market reaction makes intuitive sense — lower rates can lift affordability and sentiment — yet the deeper lesson is how “mortgage rates” are not a single number. They are an ecosystem of spreads, hedges, and incentives.

What a $200B MBS Bid Actually Does (And What It Doesn’t)

Think of MBS as the bridge between “what homeowners pay” and “what capital markets demand.” When MBS prices rise, their yields fall. Since mortgage rates are priced off MBS yields (plus layers of lender margins and servicing economics), a large, price-insensitive buyer can compress yields quickly — especially when market makers are cautious and liquidity is thin.

This is why the move is often described as a “mini-QE.” It is not the same as broad-based quantitative easing, but it can rhyme with it: concentrated buying pressure aimed at a specific rate channel. In plain language, it attempts to lower the cost of the 30-year money that households actually use — not just the overnight policy rate that economists debate.

Here’s the key nuance: mortgage rates are not simply “Treasury yield + a small constant.” They include an MBS spread that expands and contracts based on risk appetite, volatility, and technicals. A targeted bid can shrink that spread even if Treasury yields don’t move much.

Why Rates Can Fall Even If the Fed Doesn’t Cut

Markets often treat the Fed as the single steering wheel for all rates, but mortgages are driven by a different set of hands. MBS investors are constantly pricing prepayment risk (people refinancing when rates fall), extension risk (durations lengthening when rates rise), and the cost of hedging that convexity. When volatility is high, lenders widen margins; when volatility calms or a big buyer stabilizes MBS, margins can tighten.

So the mechanism is less “the Fed turned dovish overnight” and more “the spread component improved.” A government-linked purchase program can reduce the premium investors demand for holding MBS, and it can reduce hedging stress in the system. That’s why rate drops can arrive suddenly — and why they can fade just as fast if the market doubts the program’s durability.

If you want a practical frame: the Fed is the thermostat, but MBS purchases are the ductwork. You can push more cool air into one room even if the whole house thermostat hasn’t changed — but you might create pressure imbalances elsewhere.

Affordability Math: The Difference Between a Narrative and a Payment

Headlines about “rates falling” matter only if they change monthly payments enough to alter behavior. A 0.10% move might boost confidence yet barely change affordability; a 0.50% move can pull real demand forward — especially for buyers sitting at the edge of qualification.

To keep it concrete, here are illustrative payment sensitivities for a 30-year fixed mortgage (principal & interest only; taxes/insurance and down payments can change the outcome materially). The point isn’t the exact dollar amount — it’s the direction and the magnitude needed to move the needle.

• A $425,000 loan at 6.21% vs. 5.99% lowers the monthly principal-and-interest payment by roughly $60.

• A $1,000,000 loan at 6.21% vs. 5.99% lowers the monthly principal-and-interest payment by roughly $140.

• If rates reach 5.90% (a larger drop), the monthly savings grows, but it still must compete with housing supply constraints and buyer psychology.

In other words: lower rates help, but they don’t magically reset affordability back to 2020–2021 conditions. If home prices remain sticky and inventory remains tight, cheaper financing can simply re-inflate demand into the same limited supply — lifting prices rather than unlocking affordability.

Who Benefits First: Buyers, Builders, or Balance Sheets?

Rate cuts (or rate relief) create uneven winners. The market’s first reaction is often to bid up homebuilder stocks, mortgage lenders, and rate-sensitive sectors. But the household impact depends on timing and access: who can refinance, who has a down payment, and who can still pass underwriting.

A useful way to think about it is to split the housing market into three layers: the “payment layer” (buyers and refis), the “inventory layer” (existing homeowners and new supply), and the “credit layer” (the plumbing that funds mortgages). A policy that targets MBS is trying to influence the payment layer through the credit layer — while the inventory layer may remain the bottleneck.

Potential beneficiaries (in a generalized, non-investment sense):

• Marginal buyers who were narrowly priced out and can now qualify.

• Homebuilders if lower rates boost traffic and reduce the need for heavy buyer incentives.

• Existing homeowners who can refinance (if they aren’t already locked into ultra-low legacy rates).

Potential friction points:

• If rates fall and demand rebounds faster than supply, prices can rise, offsetting the affordability gain.

• Lenders may not pass through the full MBS benefit if volatility remains high or if operational capacity is tight.

• If the market perceives the move as politically driven and temporary, borrowers may delay decisions, waiting for “even lower” rates that never arrive.

The Macro Trade-Off: “Mini-QE” Helps Housing, But It Changes the Whole Risk Map

Targeted MBS buying is not just a housing story — it’s a liquidity story. Injecting demand into a major fixed-income segment can loosen financial conditions at the margin, compress spreads, and improve sentiment. That can be stabilizing in the short run, especially if growth is slowing and the labor market is cooling.

But the market also asks a harder question: if housing needs a policy backstop to stay functional, what does that say about underlying affordability, wage growth, and debt service capacity? A program that “works” too well can ignite a second-order effect — inflation expectations, currency sensitivity, and the perception that policy will always cushion downside.

There is also an institutional question. Housing finance in the U.S. is deeply tied to government-linked entities, which means policy actions can move quickly — but it also means markets will debate legitimacy, durability, and constraints. If investors suspect legal or political resistance, the spread benefit can reverse.

The Crypto Angle: Liquidity Narratives vs. Policy Risk

Bitcoin and other liquid crypto assets often trade like a stress barometer for global liquidity expectations. When markets sense easier financial conditions — whether through Fed cuts, balance-sheet expansion, or targeted credit support — risk appetite can rise and “duration-like” assets can catch a bid. A housing-support narrative can therefore spill into crypto sentiment even if the policy isn’t directly about crypto.

That said, the crypto impact is not one-directional. If the market interprets MBS buying as inflationary, it can push yields higher elsewhere, strengthen volatility regimes, and trigger deleveraging — the kind that can hit crypto quickly. In practice, crypto tends to respond less to the headline (“$200B buying”) and more to whether it becomes a persistent policy posture that changes the path of rates, the dollar, and risk appetite.

So the honest takeaway is balanced: a targeted liquidity lever can be supportive for risk assets in the short run, but it can also increase policy uncertainty — and uncertainty is fuel for volatility.

What to Watch Next (The Tell-Tale Signals)

Investors and observers often over-focus on the first-day move in mortgage rates. The more informative signal is whether the MBS channel stays compressed and whether housing activity responds in a measurable way. If the spread improvement holds, you’ll see it not only in rate quotes but in volumes and behavior.

Here are the practical indicators that matter more than the headline:

• MBS spreads vs. Treasuries: did spreads tighten sustainably, or was it a one-off squeeze?

• Refinance and purchase application trends: are households acting, or just watching?

• Homebuilder incentive intensity: are builders reducing buydowns, or still paying to move inventory?

• Inflation expectations and long-end yields: does the market view this as supportive or destabilizing?

• Risk sentiment: do credit spreads and volatility indices confirm “easier conditions,” or reject the story?

Frequently Asked Questions

Is this the same as the Fed doing QE?

No. It is closer to targeted support for one specific transmission channel (mortgage finance). But if it meaningfully compresses spreads and loosens financial conditions, markets may treat it as QE-adjacent in effect.

Will lower mortgage rates automatically make housing affordable again?

Not necessarily. If supply stays tight, lower rates can increase demand and keep prices elevated. Affordability is a three-part equation: rates, prices, and income growth.

Why do homebuilder stocks often react quickly to rate moves?

Because small rate changes can shift buyer traffic and reduce the need for incentives. Builders care less about the headline rate and more about whether buyers can qualify and close.

Does this guarantee a bullish move for Bitcoin?

No. Crypto can benefit from easier financial conditions, but it also reacts sharply to volatility, policy uncertainty, and leverage unwind events. The net effect depends on how persistent the policy signal becomes.

Conclusion

The drop in mortgage rates after a reported $200B MBS buying push is not just a feel-good housing headline — it’s a reminder that modern markets are driven by plumbing. When a large buyer steps into MBS, the spread component can move fast, and mortgage rates can fall even without a dramatic shift in Fed policy.

But the second chapter matters more than the first: whether the spread compression persists, whether real housing activity responds, and whether the market starts to price a broader “liquidity regime” shift. If that happens, the ripple effects can extend beyond housing into equities, credit, and even crypto narratives — not as a straight line, but as a complex feedback loop between policy, confidence, and risk appetite.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, or legal advice. Markets involve risk, and policy headlines can change quickly. Always do your own research and consider your risk tolerance.