A $200B Mortgage-Bond Push Isn’t QE—But It Could Still Move Markets (and Crypto Narratives)

The headline is easy to repeat: a Trump-directed plan to buy roughly $200 billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) through the U.S. housing-finance plumbing—often described as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—would, in theory, lower mortgage rates. The market reaction is also easy to understand: cheaper mortgages are “good,” so risk assets breathe out and rally.

But the interesting part is not the feel-good interpretation. The interesting part is the transmission mechanism—the chain of incentives that starts in the MBS market and ends in household cash flows, bank balance sheets, and the liquidity stories that power Bitcoin narratives. If the 2020–2021 era taught investors anything, it’s that the label (QE or not-QE) matters less than the plumbing.

This article unpacks what a $200B MBS purchase program can realistically do, why experts warn the impact may be limited, and what would need to happen for crypto to benefit in a durable way—without pretending there is a single “magic switch” that sends Bitcoin higher.

What “Buying $200B of MBS” Really Means

Mortgage-backed securities are bundles of home loans packaged into tradable instruments—most commonly “agency” MBS that carry guarantees from the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). When a large buyer steps in, it can raise MBS prices and lower MBS yields. Because mortgage rates ultimately reference the economics of turning a loan into an MBS (plus fees and hedging costs), cheaper MBS funding can translate into cheaper mortgages.

That translation, however, is not one-to-one. Mortgage rates are not just “Treasury yield + a small markup.” They include an originator margin, servicing value, prepayment risk, pipeline hedging, and operational frictions. In other words: even if MBS yields fall, the rate a household sees may fall by less—and sometimes with a lag.

There are also multiple ways such a program could be implemented, and the details matter:

• Secondary-market support: purchases target current-coupon agency MBS to tighten spreads and improve mortgage pass-through.

• Portfolio channel: GSE-related balance sheets expand retained holdings (where permitted) to absorb supply and stabilize pricing.

• Signal channel: the announcement alone changes expectations about future housing policy, refinancing incentives, and broader financial conditions.

It’s tempting to call any large bond-buying “QE,” but that shortcut can mislead. The Federal Reserve’s QE changed the size and composition of the central bank balance sheet and explicitly targeted broader financial conditions. A housing-finance-directed purchase program can still be powerful—but it is narrower, more political, and often more constrained by the structure of the mortgage market.

Why the Pass-Through to Mortgage Rates Can Be Smaller Than People Expect

The most common misunderstanding is assuming that if you lower MBS yields by X, you lower mortgage rates by roughly X. In reality, the mortgage rate a borrower gets reflects a chain: Treasury yields influence MBS yields, MBS yields influence the rates lenders can offer, and lenders then layer on costs, credit overlays, and a profit margin. Each link can widen or tighten depending on competition, regulation, and volatility.

Another subtlety is that MBS are “negatively convex.” When rates fall, borrowers refinance, shortening the life of an MBS. That prepayment risk forces investors to hedge dynamically and demand compensation. In stressed or volatile periods, that compensation can rise faster than you’d expect—so even aggressive buying may produce only a modest decline in retail mortgage rates.

Three reasons the effect may be limited—even if $200B sounds enormous:

• Capacity constraints: lenders can only process so many refinances, appraisals, and closings. When pipelines fill, lenders protect margins instead of cutting rates aggressively.

• Spread stickiness: the “primary–secondary spread” (what borrowers pay vs. what MBS investors earn) can remain wide if volatility is high or competition is weak.

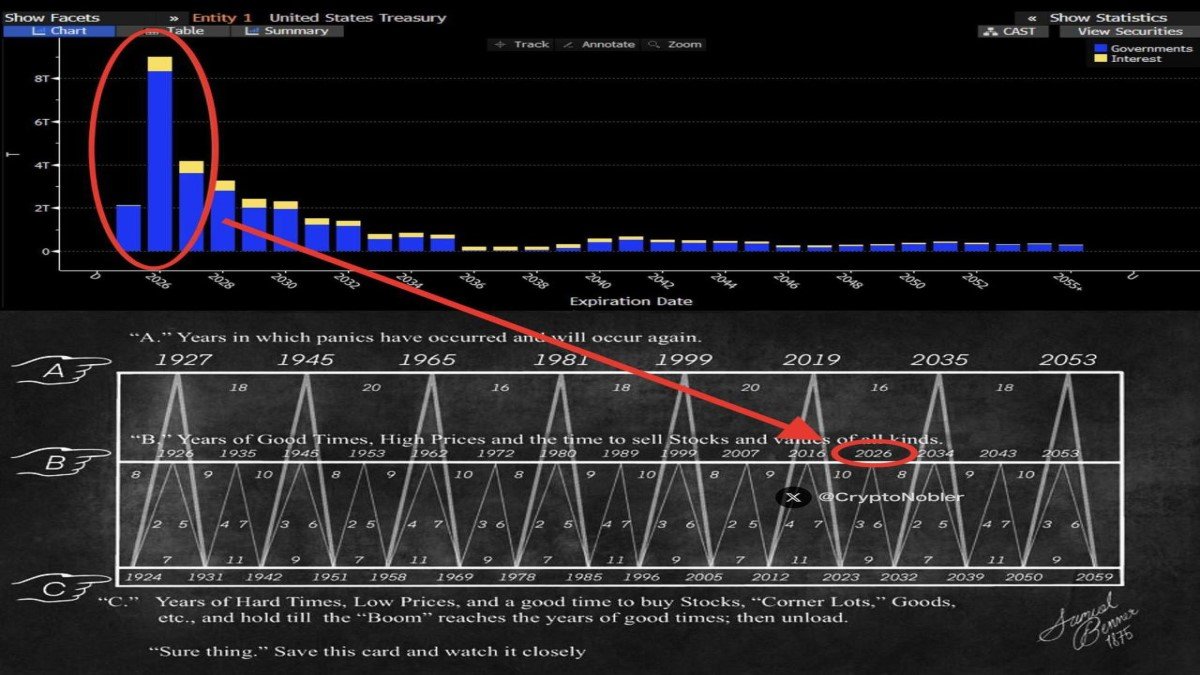

• Term structure reality: if longer-dated Treasury yields rise (because deficits, inflation expectations, or term premium rise), MBS buying has to fight a headwind.

That last point is why market professionals often talk about “narrowing spreads” rather than “lowering rates.” A program can improve conditions at the margin—say, by shaving 0.1% to 0.5% off mortgage rates under favorable conditions—yet still struggle to transform affordability if home prices and longer-term yields remain elevated.

Mini-QE, Fiscal Plumbing, or Something Else? How to Classify the Move

Calling this a “mini-QE” is emotionally satisfying because it fits a familiar template: big buyer + bonds = easing. But classification is not semantics; it changes how you interpret second-order effects. True QE tends to be broad-based: it compresses risk premia across markets, boosts bank reserves, and often weakens the currency at the margin. A targeted MBS program mainly attacks one wedge: mortgage spreads.

So the right mental model is closer to a spread-compression intervention than to pure monetary easing. It tries to improve the functioning of a specific market that has outsized social and political importance. That distinction matters because the “wealth effect” and the “liquidity effect” can diverge. Housing can get a short-lived sugar rush even if the broader economy does not get lasting stimulus.

Here is a practical way to think about it:

• If the program primarily reallocates private demand (crowding in investors by reducing volatility and hedging costs), it’s market plumbing.

• If it effectively creates net new demand without meaningful constraints (and is financed in a way that expands system liquidity), it starts to look more like macro easing.

• If it triggers a political cycle of “support housing at all costs,” it becomes a policy signal with risk-asset implications far beyond mortgages.

What Could Break the “Limited Impact” Argument

It’s easy to sound clever by saying “this won’t matter much.” Markets punish that kind of certainty. The impact can become meaningful if the program hits at the right time—specifically when spreads are already wide, volatility is calming, and lenders are hungry for volume.

In that context, MBS purchases can change the microeconomics of mortgage lending: originators compete harder, refinancing picks up, and household monthly payments fall enough to free up cash flow. The psychological effect can matter too: lower mortgage rates can stabilize homebuyer expectations, which stabilizes housing activity, which stabilizes construction employment and local credit demand.

Watch these “make-or-break” conditions:

• Mortgage volatility: if volatility declines, spreads can compress quickly and pass-through improves.

• Lender competition: if lenders fight for market share, savings reach borrowers faster.

• Supply response: if housing supply remains constrained, lower rates may simply bid up prices, blunting affordability gains.

The final condition is the uncomfortable one: if the policy lowers rates but reignites home-price inflation, it can worsen the very problem it claims to solve. That creates political pressure for more interventions, tighter credit rules, or new forms of housing subsidy—each with its own market consequences.

The Crypto Angle: When “Easing” Becomes a Narrative Trade

Crypto does not need housing to boom. It needs something more abstract: a credible story that liquidity is returning, that risk premia are compressing, and that the path of least resistance for capital is toward higher-beta assets. A large MBS-buying program can feed that story even if its real-economy impact is modest.

However, there’s a difference between a narrative tailwind and a liquidity regime shift. Bitcoin tends to react most strongly when investors believe a broader pivot is underway—such as a shift toward lower policy rates, slower balance-sheet runoff, or explicit tolerance for easier financial conditions. A targeted mortgage program can be interpreted as the first domino, but the rest of the dominoes still have to fall.

Here are three pathways where the policy could support crypto—without turning this into a simplistic “money printer” meme:

• Risk appetite channel: if equities interpret the move as supportive, portfolio risk budgets expand, and crypto benefits as a higher-beta satellite exposure.

• Dollar liquidity expectations: if markets infer reduced tightening (or increased quasi-fiscal support), the perceived scarcity of dollars eases, helping speculative assets.

• Collateral and leverage channel: better funding conditions can revive derivative activity—useful for liquidity, but also a source of liquidation risk.

It’s also worth stating the bearish version: if investors interpret the program as evidence that policymakers are worried—about housing, growth, or political legitimacy—then the same policy can increase macro uncertainty, strengthen demand for cash, and pressure risky assets in the short run. Crypto often trades like a high-volatility “growth” asset during shocks.

A More Grounded Framework for What to Watch Next

Instead of debating whether this is QE, watch whether it changes measurable spreads and behavior. The mortgage market is one of the most data-rich markets in the world. If the program works, you should see it in a handful of indicators before you see it in headlines.

Start with the plumbing, then move outward:

• Agency MBS spreads: are current-coupon MBS yields tightening versus Treasuries?

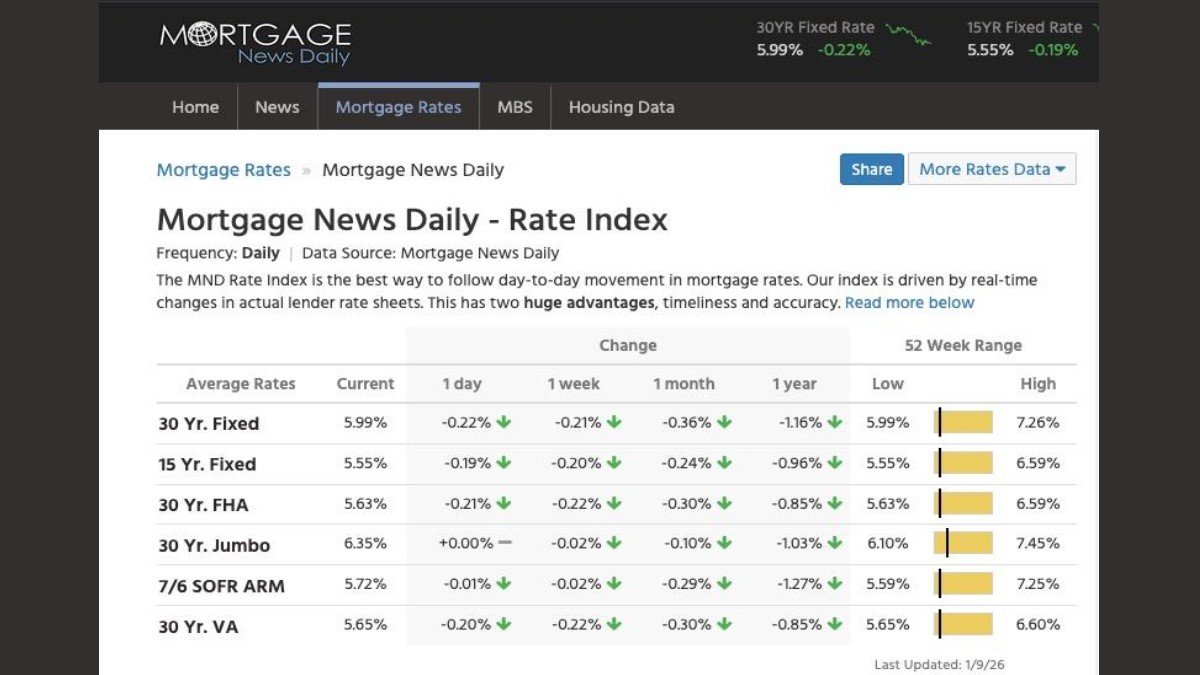

• Primary mortgage rates: do quoted 30-year fixed rates decline meaningfully, and do they stay down?

• Refinancing activity: does refi volume pick up, or are lenders still bottlenecked?

• Credit availability: do lenders loosen overlays, or do they keep standards tight?

• Broader financial conditions: are equity credit spreads tightening and volatility falling?

On the crypto side, watch whether “risk-on” is backed by durable liquidity rather than just leverage:

• Stablecoin issuance and exchange inflows: are new dollars (or dollar substitutes) actually entering the system?

• ETF flows vs. price action: is spot demand persistent or headline-driven?

• Derivatives positioning: rising open interest can support price discovery, but extreme funding and crowded positioning often precede sharp reversals.

Conclusion: A Housing Tool With Macro Echoes

A $200B push into mortgage-backed securities can be a meaningful market-structure event even if it is not true QE. Its first-order target is mortgage spreads, not the whole economy. That’s why experts caution the effect may be limited—and why investors should avoid treating it as a guaranteed mortgage-rate reset.

Yet markets don’t trade only first-order effects. They trade expectations and second-order narratives. If the policy is interpreted as the start of a broader easing posture, it can lift sentiment across equities and crypto. If it’s interpreted as a narrow political fix with unclear funding and implementation, the rally can fade as quickly as it arrived.

The cleanest takeaway is also the least exciting: watch spreads, watch behavior, and watch follow-through. The difference between a one-week headline rally and a durable regime change is not the size of the number in the press release—it’s what changes in the plumbing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is this the same as Federal Reserve QE?

Not necessarily. QE is typically a central-bank program that expands reserves and targets broad financial conditions. A targeted MBS-buying program routed through housing-finance institutions can compress mortgage spreads without delivering the same system-wide liquidity effects.

Why might mortgage rates fall only 0.1%–0.5% even with $200B of purchases?

Because mortgage rates include more than MBS yields: lender margins, servicing economics, hedging costs, and capacity constraints all matter. In volatile periods, spreads can remain sticky even when a large buyer steps in.

Does lower mortgage rates automatically mean Bitcoin will rise?

No. Bitcoin responds to a mix of liquidity expectations, real rates, risk appetite, and positioning. A mortgage program can contribute to a “easing” narrative, but crypto tends to react most strongly when broader monetary and liquidity conditions shift.

What’s the single most important thing to watch?

Whether agency MBS spreads tighten in a sustained way and whether that tightening passes through to primary mortgage rates. If spreads compress but mortgage rates barely move, the real-economy impact is likely small—and the market narrative may outrun the data.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or investment advice. Markets involve risk, and policy outcomes can change quickly. Always verify information with primary sources and consider professional guidance where appropriate.