$238B in Short-Term T-Bills: Liquidity Test for Markets and What It Means for Bitcoin

The calendar of the US Treasury for mid-December looks crowded. Over a span of just a few days, Washington will auction roughly $238 billion in short-term Treasury bills: 13-week, 26-week and 6-week maturities, followed by a 17-week bill. At the same time, the federal debt stock has climbed to around $38.4 trillion, already several trillion dollars larger than US annual GDP.

For many observers, the combination of rapid issuance and a towering debt figure raises an uncomfortable question: is the US government quietly running low on cash, and will it once again need markets — and possibly the Federal Reserve — to absorb a huge amount of paper in a very short period of time?

This article takes a closer look at what these auctions actually represent, why they are happening now, and how they could influence interest rates, risk appetite and crypto markets. The goal is not to amplify fear, but to unpack the mechanics behind the headlines so that investors can interpret them with a clearer, more measured framework.

1. What the $238B T-bill auctions really are

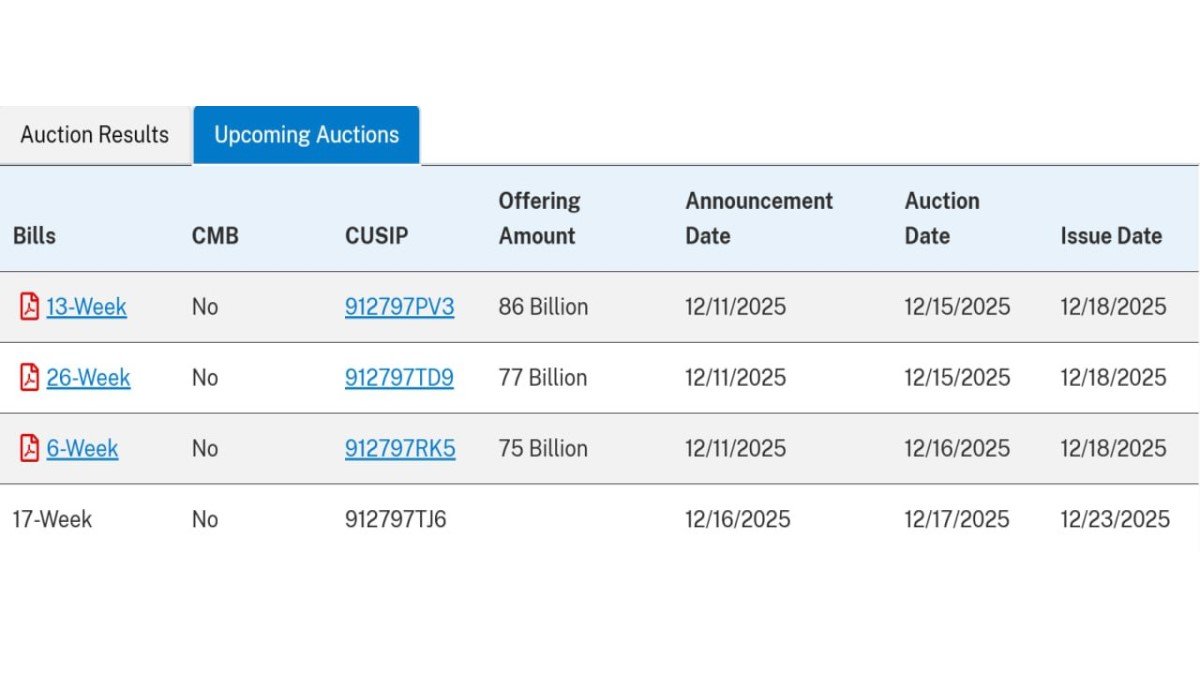

The table from the Treasury's website shows a cluster of upcoming auctions:

- 13-week bills: $86 billion

- 26-week bills: $77 billion

- 6-week bills: $75 billion

- 17-week bills: size to be announced around the time of auction

Combined, the first three lines account for the $238 billion that has drawn so much attention.

Treasury bills (T-bills) are the shortest-term securities the US government issues. They mature in a year or less and are sold at a discount, with the buyer receiving face value at maturity. The difference between the purchase price and the face value is the investor's yield.

Importantly, most of this issuance is not “new” borrowing. It primarily has three purposes:

- Refinancing maturing bills that come due on 18 December and in the weeks that follow. As old obligations mature, the Treasury sells new bills to repay the holders of the previous ones.

- Providing short-term cash to cover regular government spending between tax collection dates.

- Managing the Treasury General Account (TGA), essentially the government's main bank account at the Federal Reserve, to keep balances within a target range.

On the surface, then, the $238B figure is less shocking than it looks: the US constantly rolls over large volumes of short-term debt. However, the context matters. When the stock of total debt is already very high and interest rates remain elevated, each wave of refinancing adds pressure on the federal interest bill and on the ability of markets to absorb supply without pushing yields higher.

2. Is the US government “running out of money”?

It is tempting to read the auction schedule and conclude that Washington is close to running dry and needs to raise emergency funds. The reality is more nuanced.

The US government does not operate like a household. It does not save cash until it can “afford” expenditure, nor can it literally run out of dollars in the way a private entity can. As long as Congress has authorised borrowing and investors are willing to buy Treasury securities, the government can refinance existing debt and fund new spending.

What can become problematic over time is not the mechanical ability to borrow, but the cost and sustainability of that borrowing:

- With debt around $38.4 trillion, even a modest average interest rate implies hundreds of billions of dollars in annual interest expense.

- If investors start demanding higher yields to hold US debt — either because of inflation concerns or fiscal worries — interest costs can rise faster than tax revenue, squeezing the budget.

- Heavy issuance of short-term bills concentrates refinancing risk: a large portion of the debt must be rolled over frequently, leaving the government exposed to sudden changes in market conditions.

The current cluster of auctions is therefore best understood not as a signal that the US has no cash left, but as evidence of a system that relies structurally on constant rollover. That structure works smoothly when confidence is high and yields are moderate. It becomes more fragile when investors start to question long-term fiscal discipline or when policy rates remain high for longer than expected.

3. Where the Federal Reserve fits into the picture

Whenever large auctions appear on the calendar, a natural question arises: will the Fed step in to help by buying more Treasuries? And if it does, will that fuel inflation again?

It is crucial to separate the roles of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve:

- The Treasury decides how much to borrow and at what maturity profile (T-bills, notes, bonds).

- The Fed manages monetary policy, mainly through the federal funds rate and the size of its balance sheet. In recent years it has been shrinking that balance sheet by letting securities mature without full reinvestment.

When the Fed buys Treasuries in the open market, it is not “printing money” in the simple cartoon sense. It is swapping one type of safe asset (Treasuries) for another (bank reserves). However, such purchases can ease financial conditions by lowering yields and providing more liquidity to banks and money market funds.

Wall Street's concern is that if the Fed were to absorb too much of the new issuance, it could be seen as sliding back toward an ultra-accommodative stance reminiscent of the pandemic era. That might re-ignite inflation expectations or encourage excessive risk-taking. Conversely, if the Fed stays completely on the sidelines while the Treasury auctions a large volume of bills, yields might rise, draining liquidity from risk assets like equities and crypto.

At the moment, the Fed has framed its upcoming purchases of short-term Treasuries as a technical operation to stabilise the banking system's reserve levels, not a broad attempt to drive down long-term yields. The scale of those purchases (around $40B over a month in the latest guidance) is smaller than the gross issuance figures and is expected to be offset by other balance-sheet dynamics. Nevertheless, markets will watch closely for any sign that these operations might evolve into a more persistent support program.

4. How $238B of bills can 'drain' market liquidity

Even if the auctions are mostly refinancing, they still matter for overall liquidity. When the government issues a large volume of short-term securities, investors must decide where the cash will come from. Several channels are possible:

- Money market funds rotate out of other short-term instruments, such as the Fed's overnight reverse repo facility, into new T-bills. In this case, the impact on broader markets may be modest.

- Banks and institutions buy the bills using reserves or deposits that might otherwise have supported lending or investment in other assets.

- Global investors sell riskier assets — equities, high-yield bonds, or even crypto — to participate in what they view as safe, attractive yields in US government paper.

In the second and third scenarios, the auctions can feel like the state is pulling liquidity out of the system. Capital that might have flowed into corporate credit, stocks or digital assets is redirected into financing the federal deficit. The more frequent and larger these issuance waves become, the more investors worry about a “crowding out” effect on other markets.

This is where the phrase “draining the market” comes from. It does not mean money literally disappears; rather, it shifts toward government securities and away from risk assets. For traders in Bitcoin and other digital assets, such shifts can show up as weaker inflows, thinner order books and sensitivity to any negative news.

5. What it could mean for Bitcoin and crypto markets

Bitcoin enthusiasts often see growing government debt as a long-term bullish driver: the more aggressively central banks and treasuries expand balance sheets, the more attractive a scarce, programmable asset may appear as a potential store of value. Yet, in the shorter term, the relationship between debt issuance and Bitcoin's performance is more complex.

Several mechanisms are worth highlighting:

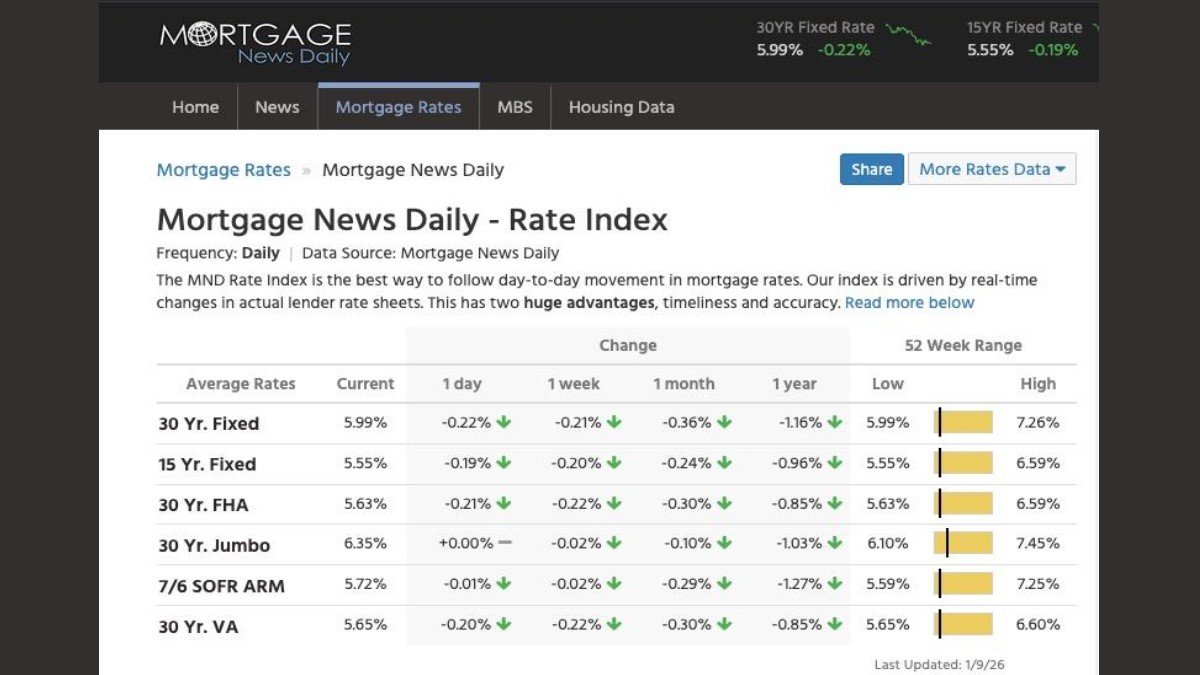

1. Safe yield competition. When T-bill yields are high, conservative investors may prefer the simplicity of short-term government paper over volatile digital assets. This can temporarily reduce demand for Bitcoin, even if long-term narratives remain intact.

2. Liquidity conditions. Large government issuance that is not offset by central bank buying can tighten financial conditions. Tighter liquidity tends to pressure risk assets across the board, from growth stocks to crypto, because leveraged positions are more expensive to maintain and marginal capital becomes scarcer.

3. Confidence signals. On the other hand, successful auctions with strong demand can reassure markets that the US still enjoys deep, reliable funding. That can support risk sentiment and, indirectly, crypto valuations.

In other words, the $238B in bills does not automatically point in a single direction for Bitcoin. Instead, it interacts with factors such as Federal Reserve policy, global risk appetite and the behaviour of large institutional players. For now, the more relevant signal may be whether flows into Bitcoin exchange-traded funds and on-chain holdings can offset any temporary pull toward safe T-bill yields.

6. Reading Treasury data more intelligently

For investors who want to go beyond headlines like “huge issuance” or “record debt,” there are several practical indicators to track:

• Bid-to-cover ratios and indirect bidding in auctions: high coverage and solid demand from foreign central banks or institutional investors suggest that the market is absorbing supply without stress.

• Treasury General Account (TGA) balance: when the government rebuilds its cash buffer aggressively, it can temporarily drain liquidity from private markets. When the TGA is being drawn down, the opposite can happen.

• Flows into and out of the Fed's reverse repo facility: if money market funds move cash from the RRP into new bills, the impact on broader risk assets may be smaller than if they sell other securities to participate in auctions.

• Term structure of issuance: a heavy tilt toward short-term bills increases rollover risk but may be less disruptive to long-term yields; shifting issuance toward longer-dated notes and bonds can push up term premiums and weigh on equity valuations.

For crypto investors specifically, combining this information with on-chain metrics — such as stablecoin supply, exchange flows and ETF creations/redemptions — can provide a more complete picture of whether liquidity is entering or leaving the ecosystem.

7. What the auctions tell us about the bigger fiscal story

Ultimately, the $238B in short-term bills is a chapter in a much longer book: how the US manages an expanding debt load in an environment of higher structural interest rates.

Several long-term themes are worth keeping in mind:

• Roll-over dependence. The more debt is held in short-term instruments, the more frequently the Treasury must return to markets. This puts a premium on confidence and stability.

• Budget flexibility. As interest payments consume a larger share of tax revenue, fiscal space for other priorities — infrastructure, social programmes, defence — becomes constrained, potentially leading to political debates about taxes and spending.

• Structural demand for safe assets. Many institutions worldwide are required or strongly incentivised to hold high-quality government paper. As long as that structural demand remains, the US can continue to refinance. The question is at what yield, and with what side effects on other markets.

• Alternative stores of value. Against this backdrop, some investors diversify into assets with different risk profiles and issuance rules, including gold and Bitcoin. Their role is not to replace the Treasury market, but to offer a hedge against extreme scenarios in which confidence in fiat frameworks erodes.

8. Key takeaways

The headline figure of $238B in short-term T-bills being auctioned over a few days can look alarming, but a more careful reading leads to a nuanced picture:

• Most of the issuance is refinancing existing obligations, not purely new borrowing.

• Nevertheless, with total debt already very high and interest costs rising, the US is increasingly reliant on markets' willingness to roll over debt at reasonable yields.

• The Fed's limited purchases of short-term bills are, for now, framed as a technical liquidity tool, not a return to massive asset-buying programmes. The balance between Treasury supply and Fed demand will be crucial for inflation expectations.

• Large auctions can feel like they drain liquidity from risk assets when investors shift funds toward attractive short-term yields.

• For Bitcoin and other digital assets, the impact is indirect: tighter liquidity and higher safe yields can weigh on prices in the short run, while long-term concerns about debt sustainability still support the narrative for scarce, alternative assets.

Rather than viewing each auction as an isolated shock, investors may find it more useful to treat them as recurring check-points in a much larger story about fiscal discipline, monetary policy and the evolving competition between traditional safe assets and new forms of digital value.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment or legal advice. All market figures are approximate and subject to change. Always conduct your own research and consult qualified professionals before making investment decisions.