Japan’s 20-Year Yield Near 3%: The End of “Free Money” and the Next Macro Test for Crypto

The chart on Japan’s 20-year government bond looks almost unreal. After spending most of the past two decades hugging levels close to zero, the yield has climbed toward 2.9–2.94%, the highest since the late 1990s. Recent data put the 20-year yield around 2.9%, while the 30-year sits near 3.4%. :contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4} For a country that spent years fighting deflation with negative rates and aggressive bond purchases, this is not just a technical breakout. It marks a regime shift in how Japan prices money, risk and time.

The implications reach far beyond Tokyo. For decades, Japan’s ultra-low yields made the yen the funding currency of choice for global investors. Pensions, banks and insurers borrowed cheaply in yen and bought higher-yielding assets abroad, from US Treasuries to emerging-market bonds and property. That vast web of positions is known as the yen carry trade, and the new yield landscape calls parts of it into question.

In parallel, the digital-asset market is maturing into a macro-sensitive asset class. Bitcoin did not exist the last time Japan’s 20-year yield was near 3%. The current repricing therefore doubles as the first real test of how a fully monetized crypto ecosystem behaves when one of the world’s major funding engines changes direction.

1. How Japan Spent 25 Years in the Near-Zero World

To appreciate why today’s move matters, it helps to recall how unusual Japan’s past quarter century has been. After its asset-price bubble burst in the early 1990s, the country slid into a long period of low growth and persistent deflationary pressures. By the late 1990s, long-term yields had already fallen below those of most advanced economies; policy rates eventually drifted all the way down to zero.

The Bank of Japan went on to pioneer several tools that later became mainstream elsewhere. It experimented with quantitative easing well before the 2008 global financial crisis and later introduced Yield Curve Control (YCC), a framework under which the central bank targeted the 10-year government bond yield directly, keeping it around zero by buying or selling bonds in whatever size was needed. :contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5} Super-long maturities like the 20- and 30-year sectors were not capped explicitly, but they were heavily influenced by the overall program and by markets’ assumption that policy would stay ultra-loose indefinitely.

For investors, the message was simple: yen funding would be cheap and stable for the foreseeable future. Domestic fixed-income instruments offered little yield, so institutions looked overseas. Over time, Japanese buyers became enormous players in global bond markets. By 2023, they held around $1.1 trillion in US Treasuries alone, making Japan the largest foreign creditor of the United States. :contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6} Pension giant GPIF, with roughly ¥250–277 trillion (around $1.7–1.9 trillion) in assets, allocated large portions of its portfolio to foreign bonds and equities to escape meagre domestic returns. :contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

That environment encouraged a global reach for yield and underpinned a long era of abundant liquidity. It is precisely this backdrop that is now changing.

2. Why Yields Are Rising Now: Inflation, Policy Shifts and Market Skepticism

Three forces lie behind the recent jump in Japan’s 20-year yield.

First, inflation has finally stayed above target. After years of undershooting, Japanese consumer prices have run consistently above the BoJ’s 2% target, supported by higher import costs, a weaker yen and, crucially, a pickup in wage growth. Recent data on Tokyo core inflation show year-on-year increases around 2.5–3%. :contentReference[oaicite:8]{index=8} When inflation is persistently above target, holding long-term yields near zero becomes increasingly difficult to justify.

Second, the BoJ has started to normalize policy. In March 2024 it formally ended the QQE with YCC framework, replacing it with a more conventional regime that allows long-term yields to move more freely and nudging the policy rate out of negative territory. :contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9} Since then, officials have signalled that further rate hikes are possible as long as wage dynamics and inflation expectations remain firm. Market participants now expect the policy rate to rise from 0.5% to around 0.75% in the near term. :contentReference[oaicite:10]{index=10}

Third, markets are testing how far normalization can go. When a central bank holds yields artificially low for years, the first phase of exit is often dominated by repricing. Investors ask what the term premium should be in a world where Japan must live with positive inflation and where the BoJ is no longer capping long-term rates. Super-long sectors are especially sensitive to such reassessments: recent articles note that 20-year yields around 2.9% and 30-year yields above 3.4% are the highest since 1999, with further upside possible if the BoJ tightens again. :contentReference[oaicite:11]{index=11}

Put differently, YCC has effectively been retired, and bond markets are busy rebuilding a "normal" yield curve after a quarter-century of distortion.

3. The End of the Ultra-Cheap Yen: What It Means for the Carry Trade

For global investors, the most immediate consequence of higher Japanese yields is the potential unwinding of the yen carry trade. The basic strategy is simple: borrow or raise funding in a low-yielding currency (historically the yen), convert into higher-yielding currencies, and invest in bonds, credit or other assets that offer a spread. The risk is that the funding currency appreciates or that the higher-yielding assets sell off.

When domestic yields were near zero, Japanese institutions had a strong incentive to buy foreign bonds. US Treasuries offered 2–4% yields; emerging-market debt and global credit offered even more. But if 20-year Japanese government bonds now yield almost 3%, the calculus changes. Investors can earn reasonable returns without taking currency risk or foreign political risk. Super-long JGBs suddenly look like a viable core holding instead of a low-yield placeholder.

The potential consequences are wide-ranging:

• Repatriation of capital. As domestic yields become more attractive, pensions and insurers may gradually reduce their exposure to foreign bonds, including US Treasuries and European government debt. The pace is likely to be measured, but even slow rebalancing can matter in a world where Japanese investors hold over a trillion dollars of US federal debt. :contentReference[oaicite:12]{index=12}

• Higher global yields. Less foreign demand means other buyers must step in at lower prices, pushing yields higher. Recent episodes already show global bonds selling off in response to hawkish BoJ remarks, with US 10-year yields moving higher alongside JGBs. :contentReference[oaicite:13]{index=13}

• FX volatility. If Japanese investors sell overseas assets and bring funds home, they need to buy yen. That can drive rapid moves in USD/JPY and other yen crosses, especially if markets are crowded on the other side of the trade.

The net effect is to tighten global financial conditions—exactly the opposite of what the ultra-low-rate yen environment delivered for more than two decades.

4. A Structural Signal: Japan Accepts That Inflation Is Real

Beyond carry dynamics, the rise in super-long yields sends a more fundamental message: Japan appears to be accepting that deflation is no longer the central risk. For years, policymakers worried about prices falling, wages stagnating and households delaying consumption. Negative rates and YCC were justified as emergency tools to push the economy out of that trap.

Today’s yield curve tells a different story. A 20-year yield around 3% implies that investors expect positive nominal growth and persistent inflation over a long horizon. It also suggests that they see less probability of Japan dropping back into the deep deflation episodes of the 2000s and early 2010s. BoJ Governor Kazuo Ueda has hinted as much, noting that the neutral interest rate for Japan—the level consistent with stable inflation—is likely higher than previously thought. :contentReference[oaicite:14]{index=14}

This matters because long-term yields reflect not just current policy, but accumulated beliefs about a country’s economic model. Moving from a "deflation risk" regime to an "inflation management" regime changes how investors think about everything from wage negotiations to corporate pricing power to fiscal sustainability.

5. Global Feedback Loops: From US Treasuries to Emerging Markets

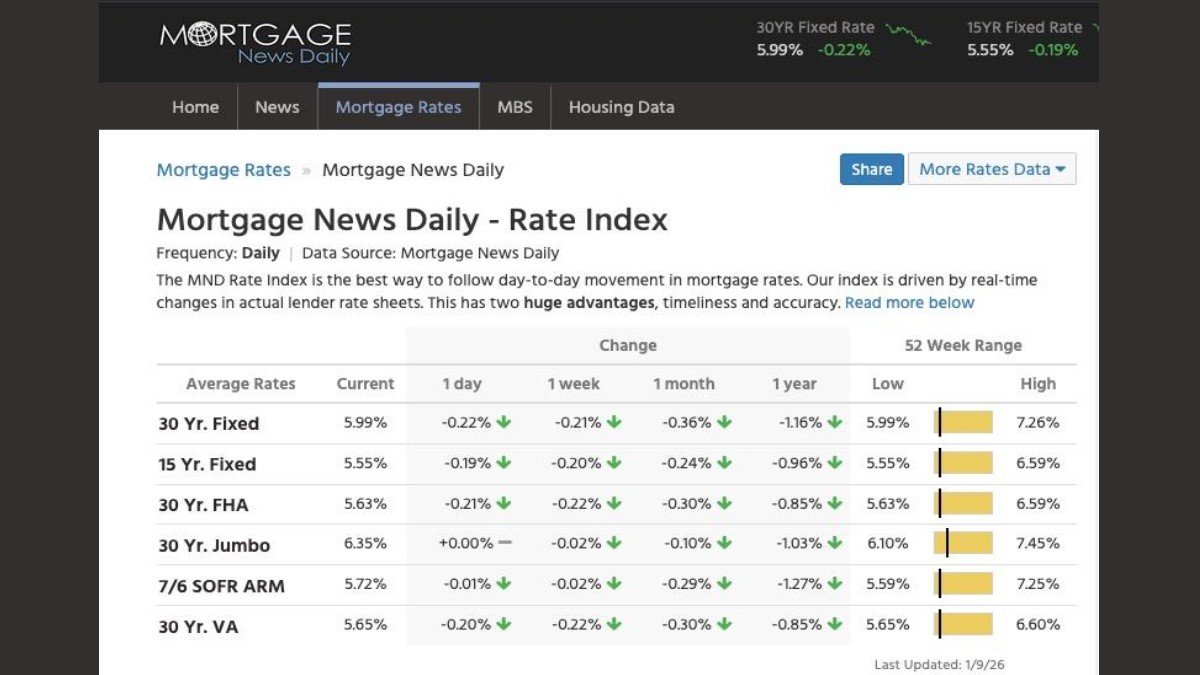

Japanese normalization does not happen in a vacuum. The United States is running large fiscal deficits, and foreign holdings of its securities reached more than $30 trillion across equities and debt by mid-2024. :contentReference[oaicite:15]{index=15} If one of the biggest external buyers of US bonds becomes less enthusiastic because it can earn solid yields at home, the US Treasury may have to offer higher yields to attract marginal investors. That can ripple through mortgage markets, corporate borrowing costs and valuations across risk assets.

For emerging markets, the risks are twofold. First, higher developed-market yields raise the global discount rate, putting pressure on asset prices. Second, the unwinding of yen-funded positions can create sudden outflows. Countries and companies that benefited from cheap yen loans in the past may face more expensive refinancing terms or reduced appetite from Japanese lenders.

None of this guarantees a crisis. But it does mean that a world accustomed to Japanese institutions quietly providing steady demand for foreign bonds must now adjust to a more balanced, sometimes even inward-looking stance from Tokyo.

6. How Crypto Fits Into This Picture

Where does Bitcoin—and the broader digital-asset complex—fit into a story about Japanese bond yields? The answer lies in liquidity and in the role of assets with fixed supply.

Historically, crypto has been highly sensitive to global liquidity cycles. When central banks inject liquidity and real yields fall, investors often search for alternative stores of value and higher-beta assets, benefiting Bitcoin and other tokens. When yields rise and policy tightens, the process can reverse. We saw a glimpse of this dynamic recently: hawkish BoJ comments that pushed Japanese yields higher coincided with a sell-off in global bonds and a drop of more than 5% in Bitcoin on the day, extending a multi-week correction. :contentReference[oaicite:16]{index=16}

Japan’s shift therefore matters in at least three ways:

• Short-term volatility. If higher JGB yields trigger unwinding of global carry trades, risk assets of all kinds—from high-growth equities to crypto—can experience sharp, liquidity-driven swings. In such phases, even strong long-term narratives do not shield prices from temporary stress.

• Relative appeal of “hard assets”. Over longer horizons, rising concerns about sovereign debt sustainability and higher nominal yields can push some investors to diversify into assets with limited supply, such as gold, certain real-estate markets and Bitcoin. The logic is that, while bonds offer fixed coupons, their real value depends on inflation and fiscal discipline; assets with hard caps or structural scarcity offer a different risk profile.

• Portfolio construction and currency risk. Investors who hold global portfolios must now think more carefully about how yen, dollar and euro exposures interact with crypto holdings. If the yen strengthens during periods of stress, it could act as a partial hedge against drawdowns in risk assets, including digital ones.

In practice, this means crypto is likely to experience a more complex cycle: periods of liquidity-driven turbulence when yields rise, followed by potential appreciation as investors look for stores of value in a world of higher structural inflation and elevated government debt.

7. Scenario Analysis: What If Yields Stay High—or Go Higher?

Looking ahead, two broad scenarios stand out.

Scenario A: Yields rise further and stay elevated. In this path, inflation in Japan remains firm, wage growth keeps surprising to the upside, and the BoJ gradually lifts its policy rate toward what it sees as neutral. Long-term yields climb above 3% and settle there. Japanese institutions accelerate their rebalancing toward domestic bonds, trimming foreign holdings. US and European yields drift higher as a result, forcing their central banks to stay cautious even if domestic inflation cools.

Under this scenario, global risk assets face recurring bouts of volatility. Bitcoin and other digital assets could see sharp corrections whenever bond markets reprice. However, the same forces that pressure valuations—concerns about debt sustainability, questions about fiat currencies with rising interest burdens—also support a narrative for scarce, non-sovereign assets over the long run.

Scenario B: Yields peak and then stabilize. In this case, the BoJ delivers a limited number of hikes and convinces markets that inflation will be contained near target. Yields around 2.5–3% come to be seen as the new normal. Japanese investors rebalance portfolios incrementally rather than dramatically; foreign bond holdings shrink slowly or plateau.

Here, the immediate shock to global markets is manageable. Bond investors absorb the new yield structure, and risk assets gradually adjust. Crypto still trades with sensitivity to rates, but the environment becomes less about sudden liquidity squeezes and more about adoption, regulation and technological progress.

Reality will likely fall somewhere between these stylized paths, with phases of repricing followed by consolidation. What matters is that the old assumption—“Japan will always provide nearly free capital”—no longer holds.

8. A Building Block in a Larger Super-Cycle Story

From a big-picture perspective, Japan’s 20-year yield near 3% is one piece of a broader transition. Around the world, the cost of capital is resetting after a decade of quantitative easing and zero rates. Governments are carrying higher debt loads, populations are aging, and supply-side constraints—from energy to labour—are more visible than in the pre-pandemic era.

In that environment, it is plausible that we are entering a multi-year super-cycle where scarcity assets—those with fixed or tightly constrained supply—play a larger role in portfolios. Gold, certain categories of land and property, and Bitcoin all fit that description in different ways. The key insight is not that they move in a straight line, but that their long-term value is less directly tethered to any single government’s balance sheet.

Japan’s normalization is an early signal within that story. When even the world’s most persistent low-rate experiment begins to unwind, investors must reconsider what “risk-free” actually means and how they want to balance income-producing assets against stores of value. For allocators who believe in the long-term potential of Bitcoin and other digital assets, the period between now and the late 2020s may be best understood as a window for thoughtful accumulation rather than a chase for quick gains.

9. Takeaways

The surge in Japan’s 20-year yield to levels last seen in the late 1990s marks the end of an era. It signals that deflation is no longer the dominant concern, that the BoJ is prepared to let markets play a bigger role in setting long-term rates, and that the era of ultra-cheap yen funding is fading. For global markets, this means more complex interactions between Japanese and foreign bond markets, new patterns in currency moves, and a gradual reshaping of who finances whom.

For digital-asset markets, the message is nuanced. Higher yields can translate into near-term volatility and liquidity stress, but they also highlight the structural reasons some investors are drawn to assets with limited supply and global accessibility. Understanding how these forces interact—rather than reacting to individual headlines—will be crucial for anyone trying to navigate the coming macro cycle.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only. It does not constitute investment, financial, legal or tax advice and does not recommend any specific asset, strategy or service. Bonds, currencies, digital assets and other instruments discussed here can be volatile and may not be suitable for all investors. Readers should conduct their own research and consider consulting qualified professionals before making financial decisions.