China’s CPI–PPI Split: A Recovery With Friction

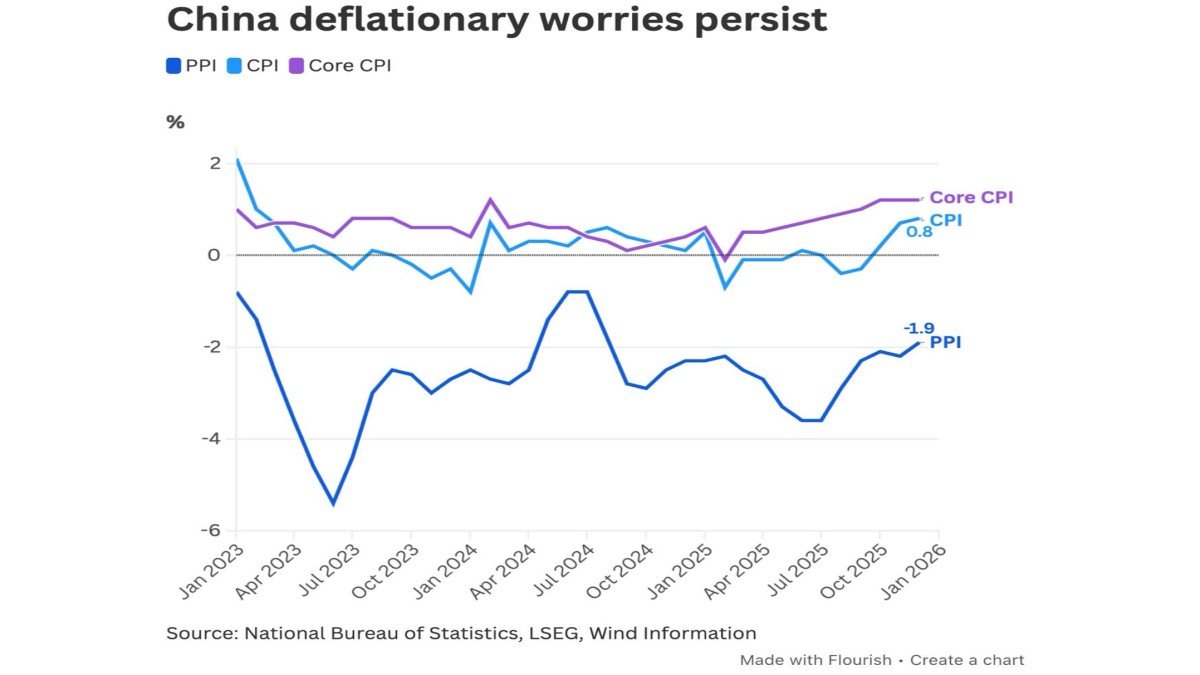

China’s inflation data rarely make global headlines unless they move sharply, yet the latest release deserves a closer look. Consumer prices rose 0.7% over the past year – the fastest pace in almost two years – while producer prices fell 2.2%. On the surface, that combination seems contradictory: how can prices faced by households be rising when prices charged by factories are still falling?

The answer is that the two gauges are not designed to tell the same story. The consumer price index (CPI) measures what ordinary citizens pay: food at the supermarket, a ride on the metro, a doctor’s consultation, a hotel stay during a long weekend. The producer price index (PPI), by contrast, measures what firms receive at the factory gate for their output – everything from steel coils and chemical inputs to machinery and electronics sold to wholesalers. In any economy, and especially in one as complex as China, it is perfectly possible for demand conditions in these two spheres to diverge.

Right now, that divergence is a useful lens on where China’s recovery is gaining traction, and where it is still fragile.

1. CPI Back in Positive Territory: Households Come Up for Air

After flirting with deflation for much of the past two years, China’s CPI is finally recording a more decisive positive reading. A 0.7% year-on-year increase is not high by international standards, but for an economy that has spent long stretches with flat or negative consumer-price growth, it is a sign that demand is no longer in retreat.

Several components are doing the heavy lifting:

• Food prices have stabilised and in some categories are moving higher. Pork cycles, vegetable supply conditions and processed food demand all play a role. While authorities have tools to smooth extreme swings – such as reserve releases – the underlying trend is firmer than a year ago.

• Services inflation has picked up. Travel, catering, entertainment and healthcare have all seen modest price increases as mobility improves and households regain confidence to spend on experiences rather than just essentials.

• Housing-related costs remain mixed. The property sector is still under pressure, but rents in some urban areas have stopped falling, and maintenance, utilities and community services have edged higher.

Importantly, the recent CPI uplift appears to be driven more by volume and mix – people consuming more services and slightly higher-value goods – than by an uncontrolled surge in basic necessities. From a policy perspective, that is exactly the kind of inflation authorities prefer: moderate, broad-based and linked to an improving job market rather than to supply shocks.

2. PPI Still Negative: Factory Floors Under Pressure

The picture for producers is much less comfortable. A 2.2% decline in PPI means that, on average, the prices Chinese factories receive for their output are lower than a year ago. This is not a one-off: producer-price deflation has persisted, in varying degrees, as global conditions shifted from post-pandemic scarcity to concerns about excess capacity.

Several forces are pulling PPI down:

• Intense domestic competition. In many industrial sectors – from building materials to certain categories of machinery – capacity is ample and demand from construction and heavy industry is subdued. Firms compete on price to keep their plants running, which pushes down the average selling price.

• External trade headwinds. Trade disputes and new tariffs in key export markets have made it harder for some producers to pass on costs. To keep orders coming from overseas buyers, factories may accept lower margins, especially in standardised goods.

• Commodity dynamics. Prices of some upstream inputs such as iron ore and energy have cooled compared with earlier spikes. That reduces output prices in heavy industry even when volumes are stable. In PPI terms, falling input costs can pull the index lower even if manufacturers’ margins are not collapsing.

The net result is a landscape in which many factories are working hard for every unit of revenue. Volume may be respectable – especially for export-oriented sectors – but the price component weighs on profitability. This is why analysts often describe China’s recovery as “quantity-driven but margin-thin.”

3. CPI vs PPI in Plain Language: The Flour and Bread Analogy

One simple way to visualize the CPI–PPI divergence is to imagine the journey from flour at a mill to bread at a bakery.

Suppose a flour supplier faces stiff competition. New mills have opened, grain prices are volatile and wholesalers are bargaining aggressively. To avoid losing contracts, the mill decides to cut the price of flour. That shows up as a decline in PPI – the price received at the "factory gate" is lower even if the mill’s costs have not fallen by the same amount.

Now follow the flour to the bakery. The bakery operates in a busy neighbourhood where foot traffic is rising. People are buying more bread, pastries and coffee; many have slightly higher incomes or feel more secure about their jobs. At the same time, the bakery’s rent, electricity costs and wages are rising. To cover those expenses and capture some of the higher demand, the bakery raises the price of its bread.

From the consumer’s perspective, a loaf now costs more – so the CPI, which tracks what shoppers pay, moves higher. But the mill, despite working hard, is earning less per bag of flour, so PPI continues to slip. The two indicators are telling a consistent story: value is being squeezed in the upstream part of the chain while more of the final consumer price is absorbed by services and distribution.

That micro-level example is exactly what current Chinese data suggest on a macro scale. Upstream factories are discounting to stay competitive, while downstream service providers and retailers are nudging prices higher in line with labour and overhead costs.

4. Profit Margins and the Health of the Corporate Sector

When CPI rises and PPI falls, someone’s margins are being squeezed. In China’s case, the brunt of that pressure falls on industrial and export-focused firms.

Many of these companies face a three-way challenge:

- Weak pricing power. In commoditised sectors, it is difficult to raise prices without losing business to competitors at home and abroad.

- Sticky costs. Wages, logistics, regulatory compliance and environmental standards add to the cost base, and these items rarely move down as fast as output prices.

- Limited domestic absorption. Some industries built up capacity during earlier investment booms. With property and heavy infrastructure growth slowing, domestic demand cannot fully absorb that capacity, pushing firms to chase external markets even at tight margins.

Over time, this environment can affect investment and employment decisions. Firms with thin or volatile profitability are less willing to commit to long-lived projects, export credit can become more cautious and hiring may lag behind revenue growth. That is one reason policymakers pay close attention to PPI even when consumer inflation looks benign: it acts as an early warning system for corporate stress.

5. Policy Implications: Stimulus, Rebalancing and the 5% Growth Target

Despite these challenges, China is still on course to approach its official growth target of around 5%, thanks in part to strong exports and public-sector support. Infrastructure spending, industrial upgrades and selective tax incentives have all played a role. Yet the CPI–PPI split underscores that the recovery is not yet broad-based.

From a policy perspective, the data present both comfort and caution:

- Comfort because modest positive CPI gives authorities room to support demand without triggering runaway inflation. They can continue to offer targeted stimulus, credit support and consumption vouchers knowing that price pressures remain manageable.

- Caution because persistent PPI deflation suggests that parts of the corporate sector may be absorbing more strain than is visible in headline GDP. If producer margins remain compressed, the risk of underinvestment or slower hiring increases, which could eventually feed back into weaker household income growth.

In the medium term, the challenge is the same one officials have highlighted repeatedly: shifting growth from investment-heavy, industry-led models toward a more balanced mix that emphasises household consumption and services. The current CPI–PPI pattern reveals progress on the demand side but also shows how difficult it is to wean the economy from an industrial structure built for an earlier era of double-digit growth.

6. Global Spillovers: Cheap Goods, Cautious Demand

China’s inflation dynamics matter far beyond its borders. When producer prices fall while output volumes remain high, the rest of the world often sees lower prices for manufactured imports. For consumers abroad, particularly in advanced economies, this acts as a disinflationary force: electronics, household goods and some machinery can remain affordable even if domestic service prices are rising.

For competing manufacturers in other emerging markets, however, sustained PPI deflation in China can feel uncomfortable. If Chinese firms cut prices aggressively to maintain export share, producers in Southeast Asia, Latin America or Eastern Europe may find it harder to compete without sacrificing their own margins. That can influence investment patterns and trade relationships across entire regions.

On the demand side, a Chinese recovery led by services and modest consumption growth–rather than by heavy construction–has different implications for commodity-exporting countries. It tends to support stable but not explosive demand for raw materials. Energy producers, metals exporters and agricultural suppliers therefore need to adjust expectations: China remains a major buyer, but the era of seemingly unlimited appetite for construction-related commodities has faded.

7. How Investors and Observers Can Read the CPI–PPI Gap

For analysts and market participants, the key is to avoid over-simplified narratives. A positive CPI reading does not mean China has fully escaped deflation risks, and a negative PPI print does not automatically signal crisis. Instead, the combination offers a rich set of clues:

• Sector rotation. Consumer-facing firms in services, tourism and selected retail categories may benefit from improving pricing power, while upstream industrials face tougher conditions.

• Policy trajectory. As long as CPI stays moderate and PPI remains soft, monetary and fiscal authorities are likely to keep a supportive bias while avoiding large-scale stimulus that could reignite property imbalances.

• Currency and rates. Mild inflation paired with cautious growth encourages a stable-to-accommodative interest-rate stance, which in turn influences global capital flows and exchange-rate dynamics.

Most importantly, the CPI–PPI divergence reminds observers that economic data should be interpreted as part of a system rather than in isolation. When consumer prices and producer prices point in different directions, the story is rarely simple – but it is often more informative than when all indicators move together.

Conclusion

China’s latest inflation figures paint a portrait of an economy in transition rather than in crisis. Consumers are slowly returning to a more normal pattern of spending, pushing the CPI to its highest rate in almost two years. At the same time, factories continue to cut prices, reflecting competitive pressures, evolving global trade conditions and the legacy of earlier investment booms.

The flour-and-bread analogy captures the essence of the moment: upstream producers are discounting even as final prices at the retail counter inch higher. This configuration supports China’s near-term growth goal and offers modest help to global efforts to contain inflation, but it also signals that parts of the corporate sector are still working through a difficult adjustment phase.

For policymakers, the challenge is to nurture domestic demand without allowing producer stress to morph into broader financial strains. For international observers, the message is equally nuanced: China remains a key supplier of competitively priced goods and a stabilising force for global inflation, yet its path back to balanced, sustainable growth is far from complete.

Educational note: This article is intended for information and analysis only. It does not constitute financial, investment, legal or tax advice, and it should not be used as the sole basis for any financial decisions. Economic data are subject to revision and interpretation. Readers should conduct their own research and, where appropriate, consult qualified professionals before taking action.