China’s CPI Tick-Up Isn’t a Turnaround: Reading the Deflationary Gravity Beneath the Headline

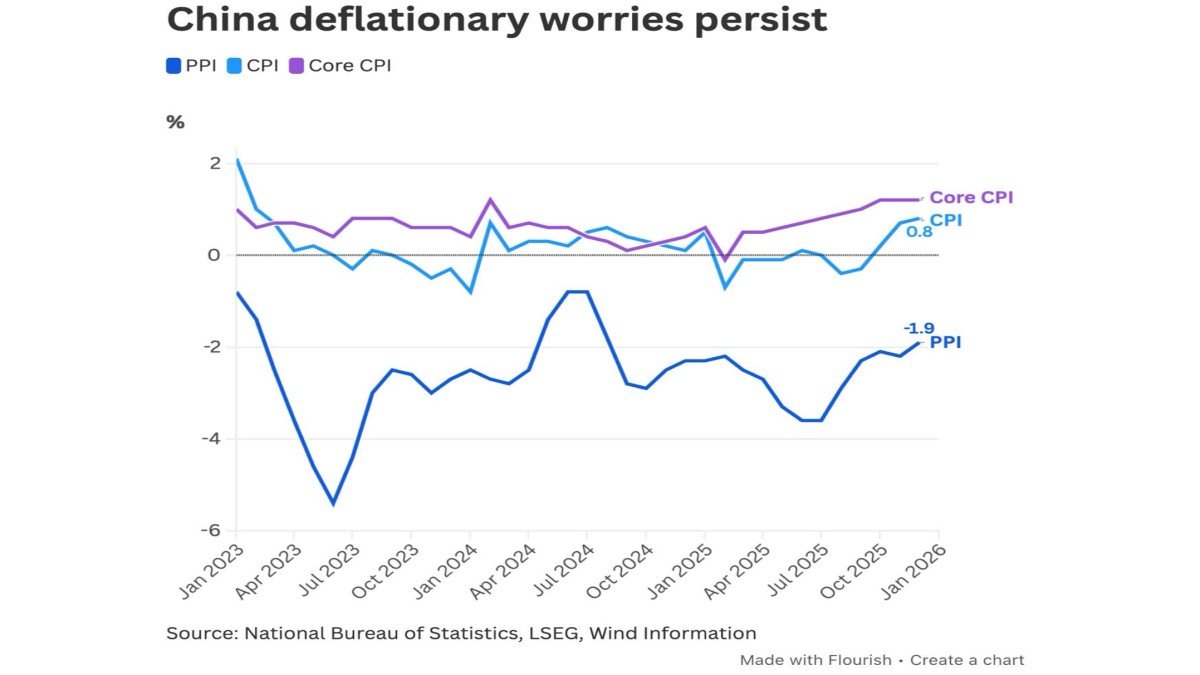

At first glance, China’s latest inflation numbers look like a small victory. Headline CPI rose 0.8% year-on-year in December—its best showing since early 2023—while core CPI reached 1.2%. In a world that has spent years arguing about “sticky inflation,” it’s tempting to read any uptick as proof that demand is back and the cycle is turning.

But the same chart that highlights the CPI bounce also shows the uncomfortable truth in darker ink: producer prices are still falling. PPI is down 1.9% year-on-year, extending a deflationary streak that has lasted years. That CPI–PPI split is not a quirky statistical footnote. It’s a map of where pricing power exists (and where it doesn’t), and it tells us far more about China’s real economic temperature than a single headline print.

Why the CPI–PPI gap matters more than the CPI headline

Think of CPI as the consumer’s mirror and PPI as the factory floor’s thermometer. When CPI rises but PPI stays negative, it often means households are paying more for a narrow basket (frequently food or regulated services) while firms still can’t pass costs through the supply chain. That combination is especially fragile because it can squeeze corporate margins without meaningfully improving wages or hiring.

This is why “CPI up” can coexist with a sluggish economy. A seasonal spike in vegetables before Lunar New Year can lift CPI for a month, yet manufacturers may still be discounting to move inventory. When businesses lose pricing power, they respond by cutting capex, pushing suppliers for better terms, and slowing recruitment—none of which supports a durable consumer rebound.

• CPI tells you what is happening at the checkout. It can be moved by seasonal food, base effects, and one-off price adjustments.

• PPI tells you what is happening in competitive industries. Persistent negative PPI is a sign that supply is still outrunning demand, and that price wars remain rational for firms trying to protect volume.

• The divergence is a signal about transmission. If stimulus is working, you normally see improving producer pricing before you see broad, confident consumer demand.

The CPI rise: a real signal, or a seasonal flare?

The December CPI increase looks impressive mainly because it breaks a long stretch of softness. Yet context matters: the move is widely attributed to food—especially vegetables—rising into the holiday period. Food inflation can be meaningful for household sentiment, but it is also the least reliable part of CPI for diagnosing whether the private economy is healing.

Core CPI at 1.2% is the more informative number, and it still describes a modest pace of underlying inflation. In a consumption-led recovery, you would expect core inflation to climb alongside services demand, travel, discretionary spending, and improving labor income. Instead, core CPI is rising from a low base while households remain cautious—an important hint that the rebound is not yet self-sustaining.

One useful mental model is to treat the CPI move as “necessary but not sufficient.” It helps that inflation isn’t collapsing, and it reduces the risk of a psychological deflation spiral where consumers delay purchases expecting lower prices later. But it does not automatically mean the economy has regained momentum—especially when the producer side is still in retreat.

PPI deflation: the price-war economy in slow motion

Negative PPI is not just about weak commodity inputs. It’s also about competition. When industries have excess capacity and demand is uncertain, firms behave defensively: they cut prices to keep factories running, protect market share, and maintain relationships with distributors. In that world, “growth” can become a race to the bottom in margins rather than a race to expand output.

China’s multi-year PPI deflation suggests a persistent mismatch between supply and demand. That mismatch shows up in the kind of stories you hear at ground level: discounts lasting longer, new products launched into saturated segments, and companies prioritizing cash flow over bold expansion. PPI is essentially the economy’s voice saying: we can produce, but we can’t sell profitably at the old price.

There is also a global dimension. When China exports manufactured goods, soft pricing at home can translate into lower prices abroad. For the rest of the world, that can feel like “imported disinflation.” For China, it can reinforce the domestic squeeze, because competing on price internationally doesn’t necessarily rebuild domestic confidence.

The property shadow: why demand heals slowly

No discussion of China’s deflation pressure is complete without property. Real estate is not only a sector; it is a balance sheet. When property values soften, households feel poorer, local governments lose a key source of revenue, and the financial system becomes more cautious. Even if consumers aren’t forced sellers, the perceived loss of wealth changes behavior—especially for big-ticket spending.

This dynamic resembles what economists call balance-sheet repair. When households and developers focus on paying down debt or simply avoiding new leverage, monetary stimulus can feel muted. Rates can fall, but borrowing appetite doesn’t necessarily rise. The result is an economy that keeps moving, yet struggles to accelerate—exactly the kind of environment where CPI can wobble higher while PPI remains negative.

That is also why policy announcements sometimes disappoint markets. Stimulus can stabilize the floor without restoring the ceiling. The question isn’t whether Beijing can support growth—history shows it can—but whether it wants to reignite the kind of credit-driven expansion that created today’s constraints.

What Beijing can do next (and what it will likely avoid)

China’s policy toolkit is broad: fiscal support, targeted credit, property measures, and incremental monetary easing. Yet the constraints are clearer in 2026 than they were a decade ago. Debt levels are higher, confidence is more sensitive, and external pressures—from trade to geopolitics—make large, blunt policy moves riskier.

If PPI deflation persists, the temptation is to “stimulate harder.” But there is a trade-off. Aggressive easing can pressure the currency, encourage capital outflows, or spark renewed leverage in the wrong places. The more realistic path is often targeted: channel liquidity toward areas that raise productivity and household security rather than simply inflating asset prices.

In practice, that means watching for measures that improve the consumer’s risk tolerance: social support, employment confidence, and credible solutions for property completion. These are slower tools, but they aim at the root problem—confidence—rather than the symptom—prices.

Global spillovers: commodities, exporters, and the inflation debate elsewhere

China’s inflation story is not purely domestic. If producer prices remain weak, that can keep a lid on global goods inflation, which matters for central banks still calibrating rate paths. It can also pressure commodity-linked economies: when China’s construction and heavy industry are subdued, demand for certain raw materials tends to soften, even if headline CPI briefly rises on food.

At the same time, a world of volatile geopolitics complicates the picture. Energy and shipping shocks can lift headline inflation globally even while China exports disinflation through manufactured goods. That creates a strange policy cocktail for other countries: sticky services inflation at home, cheaper goods from abroad, and uncertainty-driven commodity swings. China’s CPI/PPI divergence is a key ingredient in that cocktail.

For multinational companies, the implication is more operational than philosophical: pricing strategies, inventory planning, and China revenue forecasts all become harder when demand is selective and competition is intense. The “China is back” narrative is easy; running a P&L through a price-war environment is not.

A practical checklist: signals that deflation pressure is truly easing

Rather than debating a single CPI print, it’s more useful to track whether multiple gears are turning at once. Deflation pressure fades when firms regain pricing power, households regain confidence, and credit flows into productive activity rather than rollover support. Those changes show up in data with a lag, but the direction becomes clear when several indicators align.

Here are a few signs that matter more than any one month of CPI:

• PPI bottoming and stabilizing. Not just “less negative,” but broad-based improvement across industrial categories.

• Property stabilization with follow-through. Evidence that transactions and completion confidence are improving, not just isolated rescue headlines.

• Credit impulse that reaches the real economy. Loans rising is not enough; watch whether private investment and hiring respond.

• Services and wage momentum. Durable core inflation usually requires households to feel secure enough to spend.

• Currency stability. A stable yuan reduces the need for defensive policy and supports confidence in cross-border flows.

Why markets care: narratives, not just numbers

Markets don’t just price data; they price stories about data. In 2026, one dominant story is whether China can exit the “low inflation, low confidence” equilibrium without reigniting old imbalances. A headline CPI rise gives storytellers a hook, but the PPI trend is what keeps skeptics in the room.

If investors believe China is still exporting disinflation while domestic demand remains patchy, they may favor themes that benefit from slower global growth and policy support elsewhere: safe-haven currencies, selective commodities, or defensive equity positioning. If, instead, PPI turns and the property shadow lifts, the narrative can flip quickly—because the world still treats China as a marginal driver of many cycles.

The key is humility. The CPI tick-up is real, and it matters for sentiment. But the deeper message is that China’s economy is still negotiating the terms of its next growth model. Until producer prices stop falling, it’s premature to call the end of deflationary gravity.

Conclusion

China’s latest CPI print is a welcome change of direction, but it is not a clean “reflation” signal. The economy can generate pockets of consumer inflation while remaining structurally deflationary on the producer side—especially when property remains a drag and competition is fierce. The CPI–PPI gap is best read as a diagnosis of transmission: policy support has not yet restored widespread pricing power.

For observers, the most useful stance is neither alarmist nor euphoric. Watch the producer side, watch confidence, and watch whether policy targets the balance-sheet problem instead of just the interest-rate problem. That’s where the next chapter is being written—and it won’t be captured by a single month’s CPI headline.