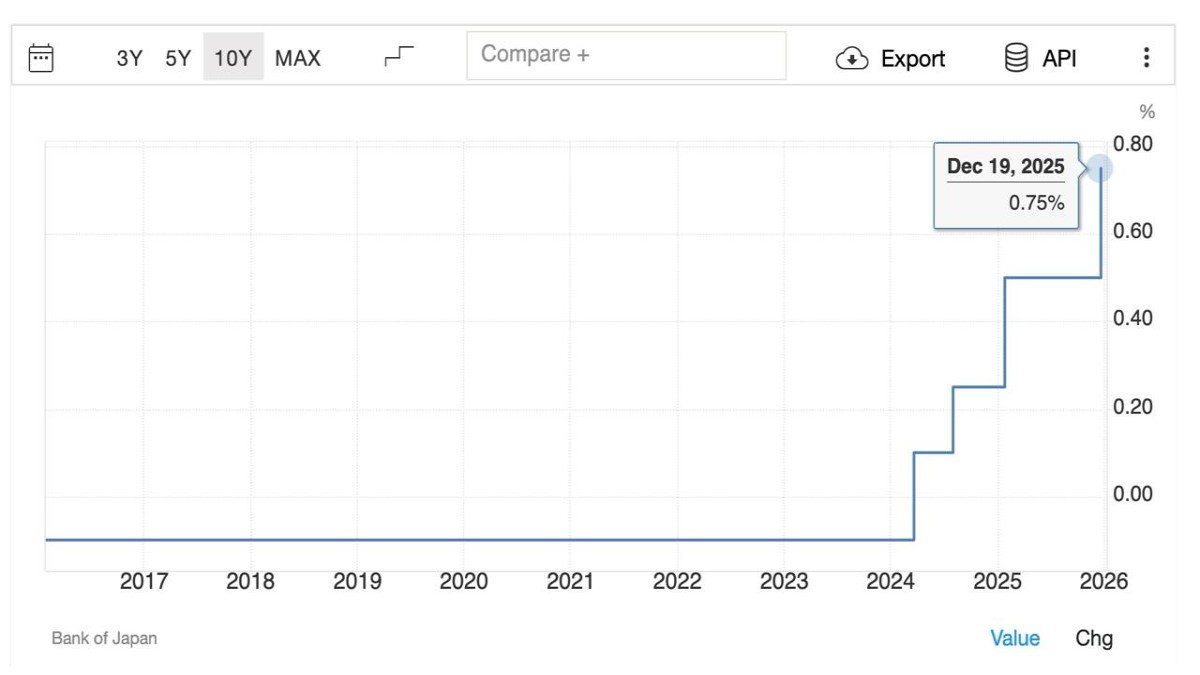

Japan’s Biggest Rate Shift in 30 Years: Why 0.75% Is Still "Easy Money"

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has just taken another historic step away from the ultra-low interest rate regime that defined Japanese policy for a generation. At its latest meeting, the central bank lifted its short-term policy rate by 0.25 percentage points to 0.75%, the highest level in roughly 30 years. On the surface this looks like a clear tightening move. Under the surface, however, Japan is still running one of the most supportive monetary stances in the developed world.

Inflation has been above the BoJ’s 2% target for 44 consecutive months, with November consumer prices rising about 2.9% year-on-year. At the same time, the yen remains weak, hovering in a broad range of 154–157 per US dollar. Against this backdrop, raising rates might seem straightforward: price pressures are sticky and the currency is soft, so the central bank responds.

The reality is more nuanced. Once we adjust for inflation, Japan’s real interest rate is still comfortably below zero. With a nominal policy rate of 0.75% and inflation near 2.9%, the effective real rate is around –2%. In plain language, the return on cash is still being eroded by rising prices. That negative real rate shapes behaviour at every level of the economy, from households deciding whether to save or spend, to global investors weighing carry trades and risk assets such as equities and Bitcoin.

1. From Deflation Fears to Persistent Inflation

For decades, Japan was synonymous with low inflation and even outright deflation. Policy makers struggled to get price growth above zero, let alone maintain it near 2%. The BoJ deployed an extensive toolkit: zero or negative interest rates, yield-curve control, large-scale purchases of government bonds and even exchange-traded funds.

That long chapter is now clearly over. Nearly four years of inflation above target signal that the economy has entered a new regime. Several drivers stand out:

- Imported cost pressures. A weaker yen made imported energy and food more expensive, pushing headline prices higher.

- Wage dynamics. After years of stagnation, wages have begun to rise more consistently, helped by tight labour markets and government pressure on large firms to boost pay.

- Shifts in corporate behaviour. Japanese companies are becoming more willing to pass higher costs through to consumers instead of continually squeezing margins.

The BoJ’s latest statement explicitly highlights this new environment. It notes that the mechanism by which both wages and prices rise moderately is likely to be maintained, and that the probability of achieving inflation consistent with the 2% target has been increasing. In other words, policy makers finally believe that their long-sought reflation has taken hold.

2. Why 0.75% Still Counts as Supportive Policy

Given that inflation is close to 3%, one might expect the central bank to move rates much higher. Many other advanced economies responded to post-pandemic inflation with rapid hikes to the 4–5% range. Japan is still far from that territory. The BoJ itself emphasises that real rates remain negative and that financial conditions are expected to continue supporting economic activity.

Understanding the distinction between nominal and real interest rates is key:

- Nominal rate: the headline figure quoted by the central bank—in this case, 0.75%.

- Real rate: nominal rate minus inflation. With inflation at 2.9%, the approximate real rate is 0.75% – 2.9% ≈ –2.15%.

When the real rate is negative, keeping money in cash or basic deposits means losing purchasing power over time. This tends to:

- Encourage households to spend on goods, services or durable items rather than hoard cash.

- Support corporations in investing in projects, equipment and even overseas expansion, since borrowing costs are low relative to expected price growth.

- Push savers to look for alternative assets—from equities and real estate to foreign bonds and, for some, digital assets.

In that sense, the hike to 0.75% is better interpreted as a step toward normalisation rather than an aggressive turn toward restrictive policy. It signals that the BoJ wants to gradually move away from the emergency settings of the past decade while still prioritising growth and wage momentum.

3. The Yen, Carry Trades and Global Capital Flows

Even after the latest move, Japanese rates remain well below those of the United States and many other major economies. This gap keeps alive one of the most important global macro strategies of the past several years: the yen carry trade.

In a carry trade, investors borrow in a low-yielding currency and invest the proceeds in higher-yielding assets elsewhere, hoping to profit from the interest rate difference and stable exchange rates. For years, extremely low Japanese yields made the yen a preferred funding currency. Capital flowed out of Japan into US Treasuries, global corporate bonds, emerging markets and risk assets such as equities and, at times, crypto.

Each BoJ rate increase chips away at the appeal of this trade, but at 0.75% policy is still far from tight. The interest-rate spread with the US remains large enough that borrowing in yen and investing in dollar assets can still make sense, especially if investors assume that currency moves will be limited.

However, the balance is shifting. A series of incremental hikes toward the 1% level that markets anticipate for 2026 would gradually raise the cost of yen funding. If global conditions become more volatile, investors might reduce carry positions, leading to repatriation flows back into Japanese assets. That, in turn, could strengthen the yen and place pressure on global risk assets that benefited from abundant, low-cost capital.

4. Japanese Households: Between Higher Wages and Negative Real Returns

For Japanese citizens, the new rate level presents a mixed picture. On one hand, the BoJ is optimistic that companies will continue to raise wages after strong pay increases in 2025. Higher salaries support consumption and help households cope with elevated prices.

On the other hand, with inflation still outpacing deposit rates, traditional savings remain under pressure. Bank deposits and safe short-term instruments are unlikely to keep pace with the rising cost of living. This can push households in several directions:

- Some may accept modest erosion of purchasing power in exchange for safety and liquidity.

- Others may diversify more aggressively into investment funds, equities or foreign assets.

- Digitally savvy investors may look at regulated digital-asset products or tokenized instruments as part of a diversified portfolio.

The government’s hope is that wage growth and supportive financial conditions reinforce each other: higher incomes encourage spending, which supports corporate revenues, which in turn justify further pay rises. But this virtuous cycle depends on confidence that inflation will remain moderate rather than accelerate uncontrollably.

5. Implications for Global Markets and Risk Assets

Because Japan is one of the world’s largest economies and a major capital exporter, BoJ policy changes ripple far beyond its borders.

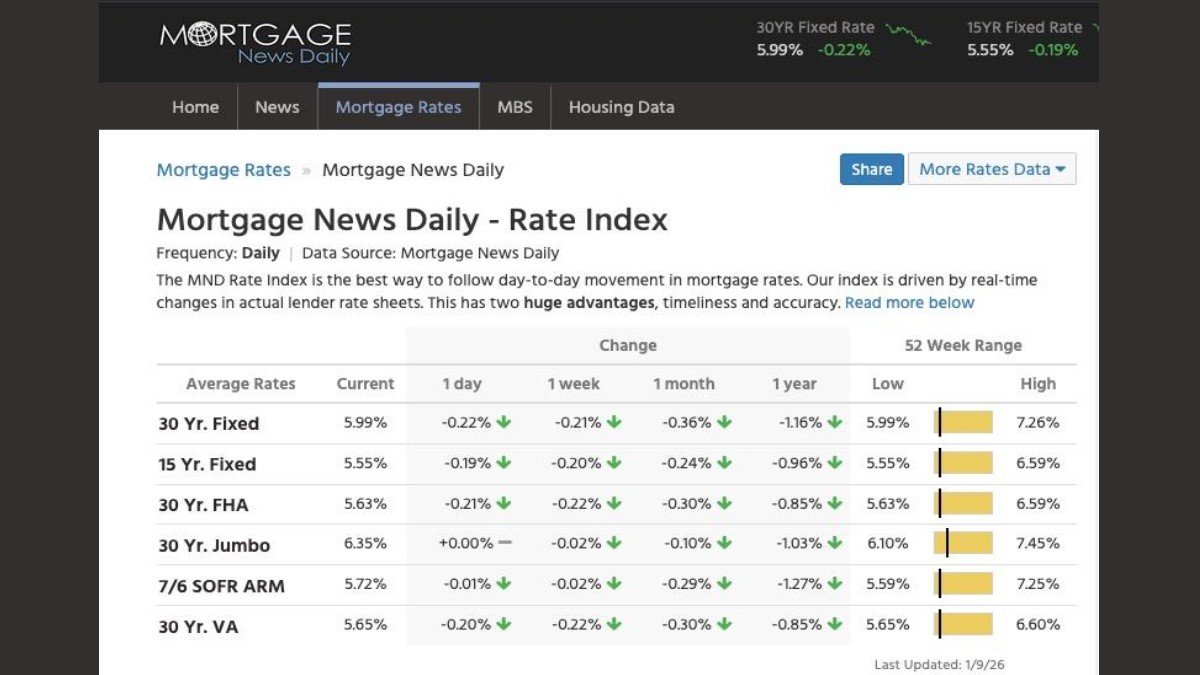

5.1 Bonds and currencies

Higher Japanese yields can draw some capital out of foreign bond markets back into domestic instruments. That might put mild upward pressure on yields elsewhere, especially if global investors reassess the relative attractions of US Treasuries versus Japanese government bonds. At the same time, any sustained strengthening of the yen would mechanically weigh on the dollar and other currencies.

5.2 Equities and corporate funding

For Japanese companies, modestly higher rates raise funding costs but also signal domestic demand that is healthier than in the deflationary years. Firms with strong balance sheets and exposure to consumers may benefit from wage-driven spending. Highly leveraged firms or those dependent on ultra-cheap credit, by contrast, may find the environment more challenging.

Internationally, a gradual tightening of the yen funding channel could make global equity markets slightly more sensitive to swings in risk sentiment. When financing is cheap and abundant, investors are more willing to hold volatile assets. When funding becomes more expensive, they often rebalance toward quality and liquidity.

5.3 Digital assets, including Bitcoin

Digital assets sit at the intersection of these forces. They are influenced both by global liquidity conditions and by investor perceptions of currency value. When major central banks keep real rates deeply negative, some participants view scarce digital assets as a way to hedge long-term debasement of purchasing power. When funding costs rise abruptly, those same assets can face short-term selling pressure as leveraged positions are reduced.

Japan’s move to 0.75% is unlikely, by itself, to transform the digital-asset landscape. But it is part of a broader story: the era of extreme monetary accommodation in one of the world’s key funding currencies is slowly ending. Over time, that may reduce the automatic tailwind that abundant carry trade flows once provided to a wide range of risk assets, from tech stocks to Bitcoin. At the same time, persistently negative real rates and a still-weak yen can keep the long-term case for alternative stores of value alive in the minds of some investors.

6. Looking Ahead: The Road Toward 1% and Beyond

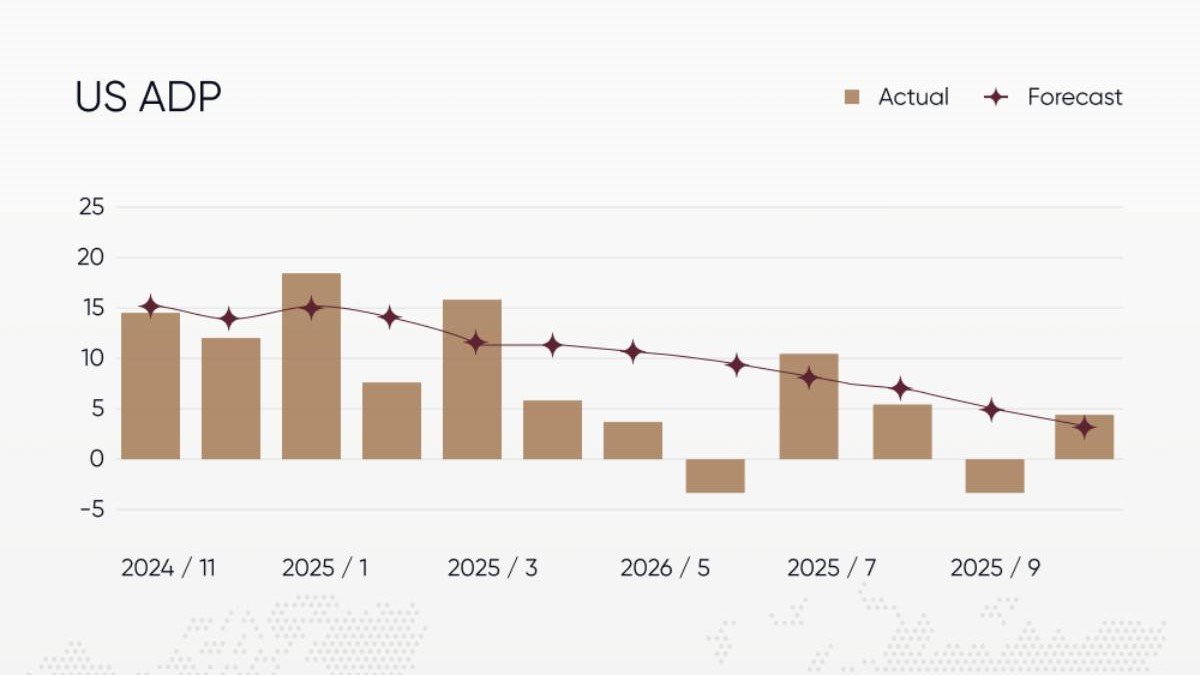

Market participants currently expect the BoJ to deliver at least one more rate hike in 2026, bringing the policy rate to around 1%. Whether that happens—and how markets react—will depend on three key variables.

6.1 The path of inflation

If inflation remains close to 3% or accelerates, pressure will mount for more decisive tightening. Conversely, if global growth slows and price pressures ease toward the 2% target, the central bank may prefer to pause and assess the impact of the moves already taken. The BoJ’s recent communication stresses that it wants to adjust the degree of monetary accommodation, not slam on the brakes.

6.2 Wage growth and corporate behaviour

The bank’s strategy assumes that wage increases will continue, supporting household income and justifying modest inflation. If wage growth stalls, the risk of returning to a low-inflation, low-growth equilibrium rises, and policymakers may become more cautious about further hikes. On the other hand, if wages accelerate significantly while productivity lags, there is a danger of profits being squeezed and investment slowing.

6.3 Global conditions and policy coordination

Japan does not operate in a vacuum. The trajectories of US and European rates, as well as global growth, will influence how far the BoJ is willing to go. A synchronized shift toward easing by other major central banks could reduce pressure on Japan to normalize rapidly. A scenario where other banks cut rates while Japan continues to hike would narrow yield differentials in a different way, potentially affecting currency dynamics and capital flows.

7. Educational Takeaways for Long-Term Investors

For readers approaching these developments from an educational angle rather than trading on short-term headlines, several lessons stand out.

• Always distinguish between nominal and real rates. A move from 0.5% to 0.75% may sound dramatic after decades near zero, but as long as inflation is close to 3%, monetary policy remains accommodative in real terms.

• Policy moves in one country can reshape global funding conditions. Japan’s role as a major provider of low-cost capital means its decisions affect everything from bond yields to appetite for risk assets worldwide.

• Household behaviour is driven by incentives, not slogans. When deposit rates trail inflation, it is rational for savers to seek alternatives, whether in domestic equities, foreign assets or regulated digital-asset products.

• Digital assets interact with macro policy in complex ways. They can benefit from long-term concerns about currency debasement yet remain sensitive to short-term swings in funding costs and investor sentiment.

8. Conclusion: A Historic Step, But Not the End of Easy Money

The Bank of Japan’s latest rate increase to 0.75% is historic because it marks the highest policy rate in 30 years and confirms that the era of negative and near-zero rates is ending. Yet it is also modest in real terms: with inflation running around 2.9%, monetary policy remains designed to support growth, investment and wage gains rather than restrain them.

For Japan, the central challenge now is to manage a delicate transition. The BoJ wants to normalise policy without undermining the fragile but important shift from deflationary psychology to a healthier environment where wages and prices both grow moderately. For global markets, the message is that one of the world’s core funding currencies is becoming slightly less free—but not scarce enough to choke off risk-taking entirely.

Investors in traditional and digital assets alike should pay attention not only to the level of Japanese interest rates but also to the direction of travel, the persistence of inflation and the response of households and corporations. Those factors will determine whether today’s 0.75% is remembered as a small step on a long path to normalisation, or as a turning point where Japan finally found a sustainable balance between supporting growth and preserving the value of money.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment, legal or tax advice. All financial decisions involve risk. Readers should conduct their own research and consult qualified professionals before making financial choices.