US–Venezuela: The Heavy-Crude Story Markets Actually Trade (and Why It Matters Beyond Oil)

Let’s make one boundary clear upfront. This is not a debate about whether intervention is right or wrong, legal or illegal. Financial markets are not moral courts, and they are not constitutional courts. Markets trade consequences. They trade what changes cash flows, supply chains, risk premia, and policy paths—often before the public conversation even agrees on what to call the event.

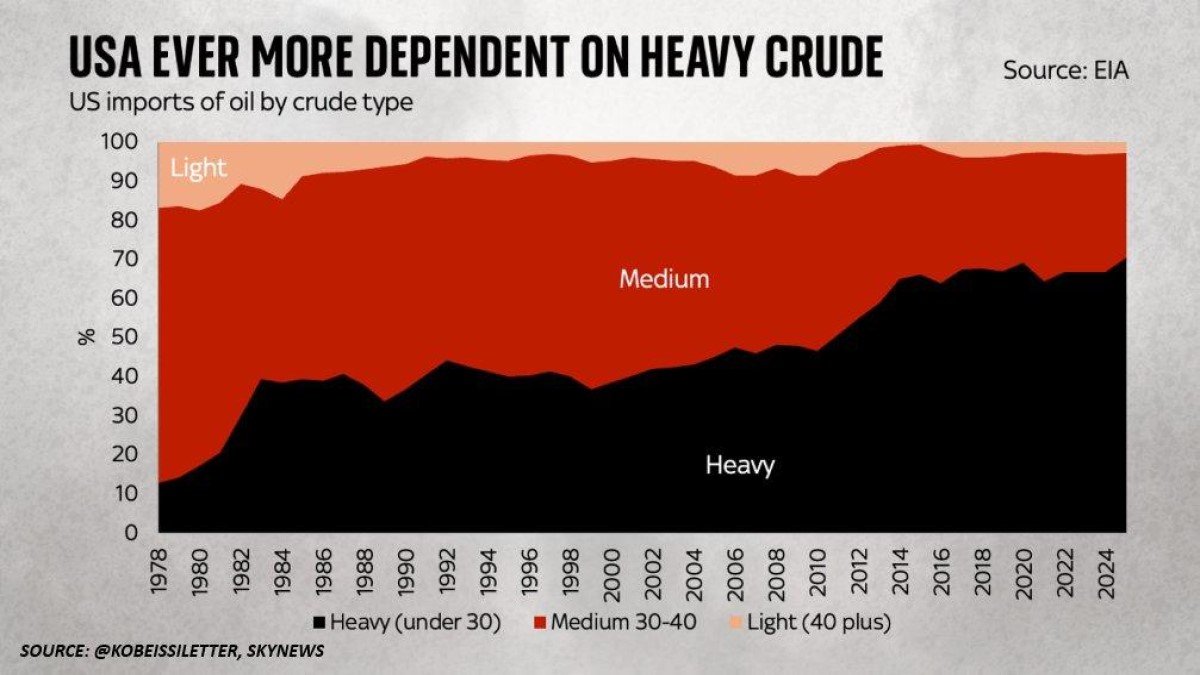

Viewed through that lens, the core economic story isn’t “Venezuela has oil.” Many countries have oil. The core story is heavy crude: the thick, high-sulfur, harder-to-refine barrels that Venezuela is famous for (especially in the Orinoco belt), and the fact that parts of the U.S. refining system—particularly along the Gulf Coast—are structurally built to process those barrels. That mismatch between what the U.S. produces (lots of light shale) and what its complex refineries can profitably run (a meaningful share of heavier feedstock) is where the market math begins.

1) The real asset isn’t “Venezuela oil.” It’s the kind of oil.

Headlines compress everything into a single word: oil. But “oil” is not one product. The grade matters. Heavy crude behaves differently from light crude in refining economics, shipping constraints, and infrastructure requirements. It’s not simply harder to pump; it’s harder to turn into high-value products without sophisticated equipment and steady operational reliability.

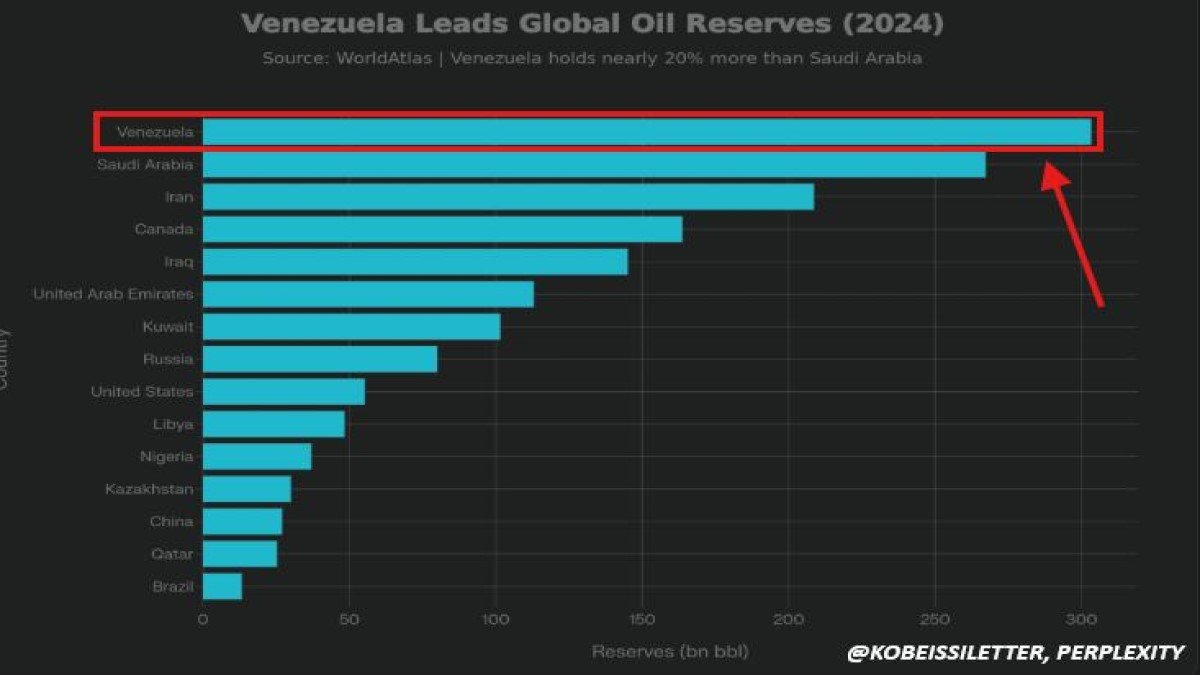

That’s why Venezuela’s often-cited proved reserves (commonly referenced around the ~300 billion barrel range) can sit in the ground for years without translating into global influence. Reserves are potential energy; production is realized energy. The bridge between the two is capital, technology, maintenance, and predictable operating conditions. Without that bridge, reserves are geopolitically impressive but economically under-monetized.

In other words: markets don’t price barrels in the ground the way they price barrels that can move—through pipes, ports, and refineries—into saleable products.

2) The U.S. refinery mismatch: shale boom up top, heavy-crude demand underneath

The United States can produce a lot of oil and still be strategically sensitive to what kind of oil it can reliably source. One of the underappreciated features of the U.S. energy system is the Gulf Coast’s concentration of complex refineries—many designed over decades to run heavier feedstocks efficiently. When a refinery is optimized for certain grades, switching the diet is not as simple as swapping ingredients.

This is where the “heavy crude” angle becomes more than a technical detail. If the U.S. increasingly depends on heavier imports (some estimates and visuals often cite a rise from roughly 10–20% decades ago toward a much higher share today), then access to heavy barrels becomes a strategic variable—not just an energy variable. In that world, Venezuela isn’t merely a country; it’s a potential input stream for a specific industrial configuration.

And that configuration is concentrated. Texas and Louisiana, in particular, sit at the intersection of refining capacity, petrochemicals, shipping, and industrial-scale power demand. When markets hear about “access” to Venezuelan resources, they don’t only think about crude prices; they also think about margins, utilization rates, and the winners/losers inside the value chain.

3) Why Venezuela’s production collapse matters more than the headline number

If you want the simplest explanation of Venezuela’s paradox, it’s this: the country didn’t “run out of oil.” It ran out of the conditions required to convert extra-heavy potential into stable production. Heavy crude extraction is capital-intensive and maintenance-sensitive. It doesn’t tolerate long periods of underinvestment the way some simpler production profiles might.

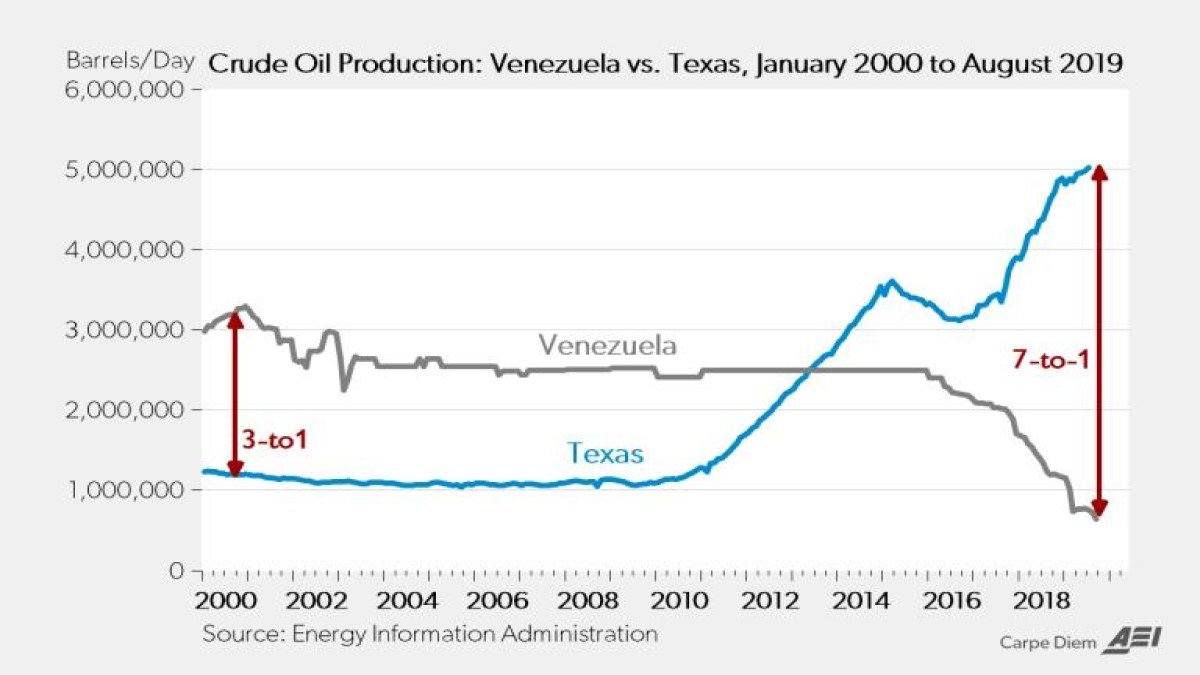

That’s why historical production paths are so important. In the early 2000s, Venezuela’s output was often cited around the multi-million-barrel-per-day range, while U.S. output was much lower than today’s shale-driven profile. By the late 2010s and into 2020, the lines look very different: U.S. production surged, Venezuela’s fell sharply. The point isn’t nostalgia. The point is that markets see a kind of embedded optionality: if infrastructure and capital return, production can recover meaningfully—especially from a depressed base.

This optionality is why markets can react in a counterintuitive way. If the narrative shifts from “disruption” to “unlock,” oil can drift down even as geopolitical uncertainty rises. Why? Because the market can simultaneously price (a) higher long-term supply access and (b) higher near-term uncertainty. Those two layers don’t cancel each other out—they show up in different assets (oil vs. gold/crypto vs. equities).

4) Reserves as leverage: why the ‘largest reserves’ headline is a bargaining chip

Charts showing Venezuela as the world’s largest oil-reserve holder are persuasive because they’re visually simple. But the market’s question is more pointed: “How many of those barrels can become reliable exports, under what governance, and on what timeline?” Reserves are leverage at the negotiating table; production is leverage in the price curve.

Still, reserve rankings matter because they shape how other major powers perceive long-run scarcity. If Venezuela truly sits at the top tier of proved reserves, then control—direct or indirect—over its energy trajectory becomes a multi-decade strategic advantage. Not because it guarantees profits every quarter, but because it can influence the marginal barrel that sets global balances during tight regimes.

There’s also a subtler industrial point. A country with large heavy crude reserves is not interchangeable with a country that produces abundant light sweet crude. In a world where refining complexity is concentrated, heavy crude can be “strategic scarcity” even when total oil barrels are abundant.

5) Follow the second-order effects: margins, defense budgets, and infrastructure

Markets are rarely moved by the first-order story alone (“oil goes up” / “oil goes down”). They move on second-order effects: which balance sheets improve, which costs rise, which budgets expand, and which industries gain a tailwind from policy response. That’s where this story can become economically consequential beyond the commodity tickers.

If the U.S. signals that major oil companies will invest in restoring or expanding Venezuela’s energy infrastructure, the immediate market translation is not “Venezuela becomes rich tomorrow.” It’s more practical: higher capex flows, engineering contracts, logistics demand, and potentially improved refining feedstock economics. The timeline matters—heavy crude projects can be slow—and the operational risks are real. But directionally, capex announcements can reprice parts of the energy value chain long before barrels actually increase.

At the same time, sustained geopolitical involvement often raises baseline spending on security, surveillance, logistics, and regional stabilization. That can benefit defense contractors and adjacent technology providers, while also increasing geopolitical risk premia in the short term. Both can be true: some sectors gain a tailwind, and the macro risk surface widens.

What the market will likely watch is not the rhetoric. It’s evidence of execution: licenses, contracts, shipping flows, refinery run rates, and changes in spreads.

6) China and Russia: why this isn’t just bilateral

A useful rule in geopolitics is that every major action has an audience beyond the named counterpart. Venezuela’s oil has been economically relevant to multiple powers, including China as a significant buyer in recent years and as a historical financier via oil-linked arrangements (figures like “tens of billions” are often discussed in public commentary, though precise totals vary by source and time window).

If the U.S. gains greater influence over Venezuelan export flows and infrastructure direction, that influence is not merely about U.S. supply. It affects China’s access expectations and bargaining power. It also has implications for Russia, which has its own energy influence and—in certain grades—its own relevance to heavy-crude dynamics. The strategic effect is not necessarily “one country wins.” It’s that leverage gets redistributed. Markets price redistribution because it changes the range of plausible futures.

This is one reason why you may see reactions in non-obvious places—like Chinese energy equities, shipping-related names, or emerging-market credit—while headline oil prices remain relatively calm.

7) The AI energy angle: why this story can touch the ‘power economy’

One of the most important shifts of the last two years is that energy is no longer only about transportation and industry. It’s also about computation. AI requires data centers; data centers require steady electricity; steady electricity still depends heavily on a mix of natural gas, oil-linked supply chains, and grid reliability. Even when the long-term transition narrative remains intact, near- and medium-term energy security becomes more valuable in an AI buildout cycle.

Venezuela’s energy endowment is not limited to crude. Public discussions often cite substantial natural gas resources as well. Whether and how those resources can be developed is a separate question—but the macro point stands: energy abundance can become strategic infrastructure for the “compute era.” That’s why markets may interpret energy access stories not just as commodity stories, but as industrial policy stories.

In this framing, the question becomes: does the event increase the probability of lower energy input costs and higher reliability for the broader U.S. industrial stack? If yes, that can support a risk-on bias even when geopolitics is noisy—especially for sectors sensitive to power costs and capital expenditure cycles.

8) What markets will likely watch next (beyond the headlines)

It’s too early to claim a definitive market outcome from one session. The first reaction often reflects positioning and liquidity more than fundamentals. But markets will start separating short-term fear from medium-term expectation as more tradeable data appears.

Rather than focusing on generalized “risk sentiment,” a more grounded approach is to watch the specific transmission channels that would validate or invalidate the heavy-crude thesis:

• Refinery indicators: Gulf Coast utilization, crack spreads, and heavy/light differentials (signals of how valuable heavy feedstock is in practice).

• Policy mechanics: licensing, sanctions adjustments, and the operational permissions that determine whether investment can actually occur.

• Shipping and flows: tanker routes, port activity, and export volume signals (markets trust flows more than speeches).

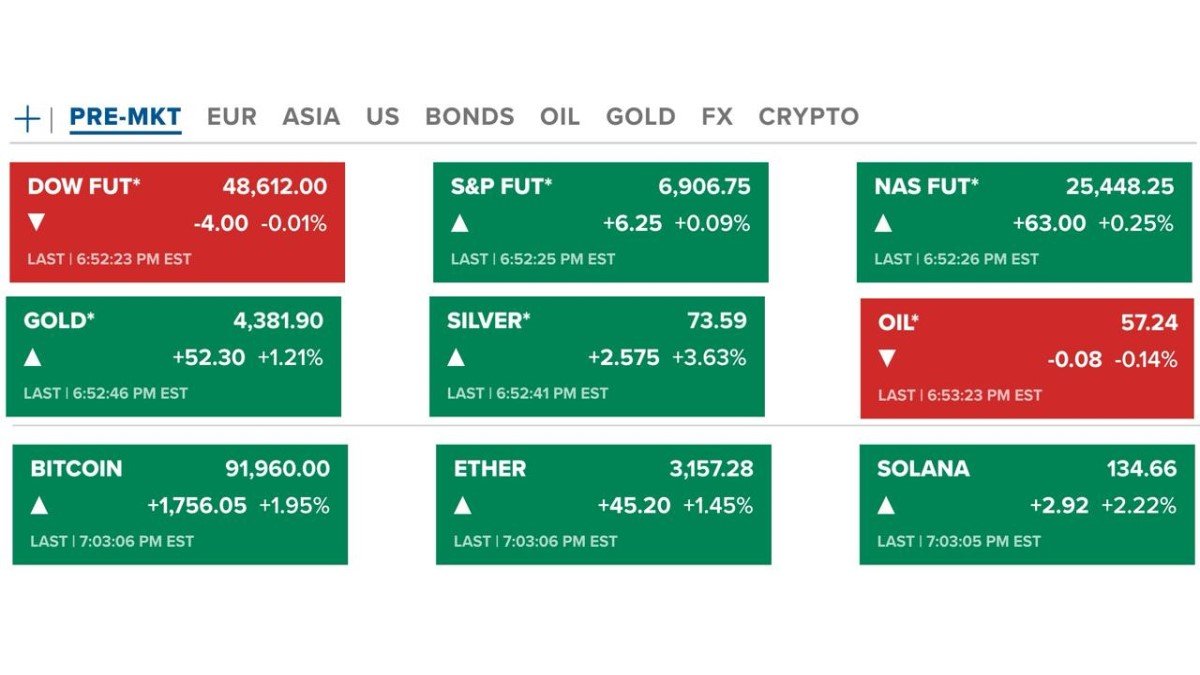

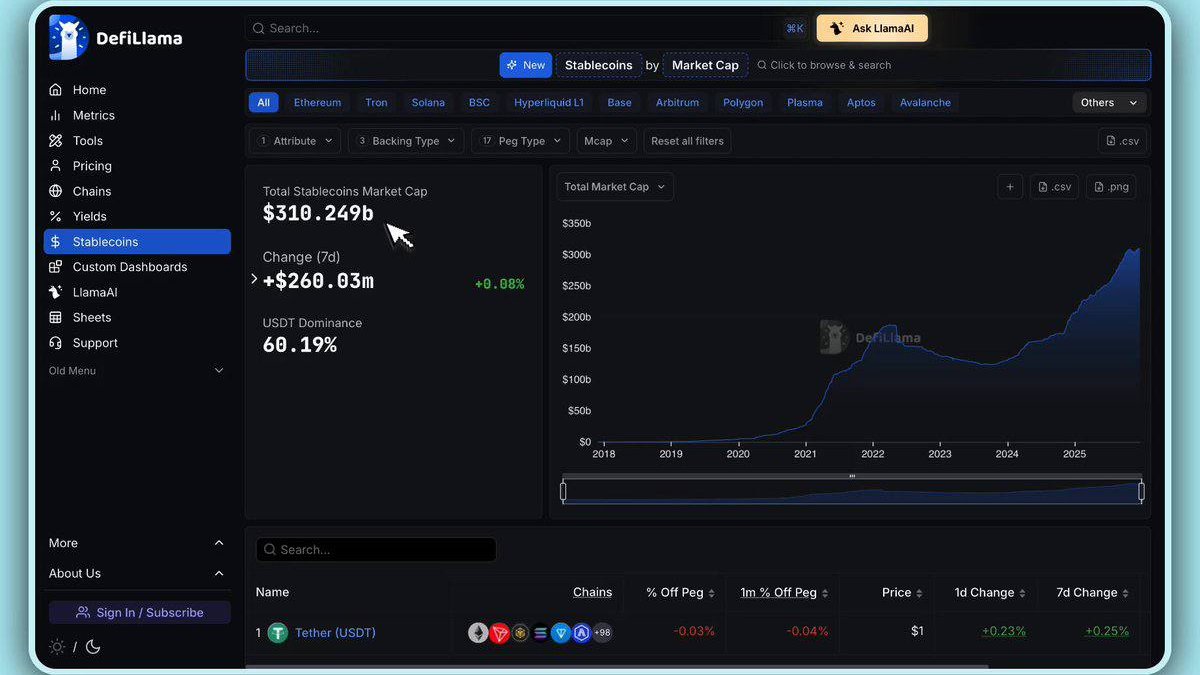

• Cross-asset hedges: whether gold and Bitcoin stay bid (a sign uncertainty remains elevated) while equities stay stable (a sign the event is seen as containable).

• EM credit and currency signals: a real stress signal often appears in funding markets before it appears on equity screens.

If these channels begin to align, the market narrative will harden. If they don’t, the story may remain headline-driven and episodic, with volatility concentrated in pockets rather than broad indices.

Conclusion

The cleanest way to understand the US–Venezuela situation through a market lens is to stop thinking in slogans and start thinking in industrial inputs. The centerpiece is heavy crude: difficult, expensive, infrastructure-dependent—and strategically valuable to parts of the U.S. refining system. Venezuela’s vast reserves are real leverage, but only production and export reliability can turn that leverage into market power.

From here, the market will likely trade the gap between narrative and execution: contracts, licenses, flows, and margins. If those begin to move, the consequences will spill beyond oil into refining economics, defense spending expectations, infrastructure cycles, and even the energy assumptions that sit underneath the AI buildout. That’s why this story matters—even if crude’s first reaction looks muted. Markets often whisper before they speak.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does “heavy crude” matter more than total oil reserves?

Because refinery systems are built around specific feedstock qualities. Heavy crude requires complex refining and stable infrastructure. Large reserves don’t automatically translate into exports or influence unless production, upgrading, and logistics can operate reliably.

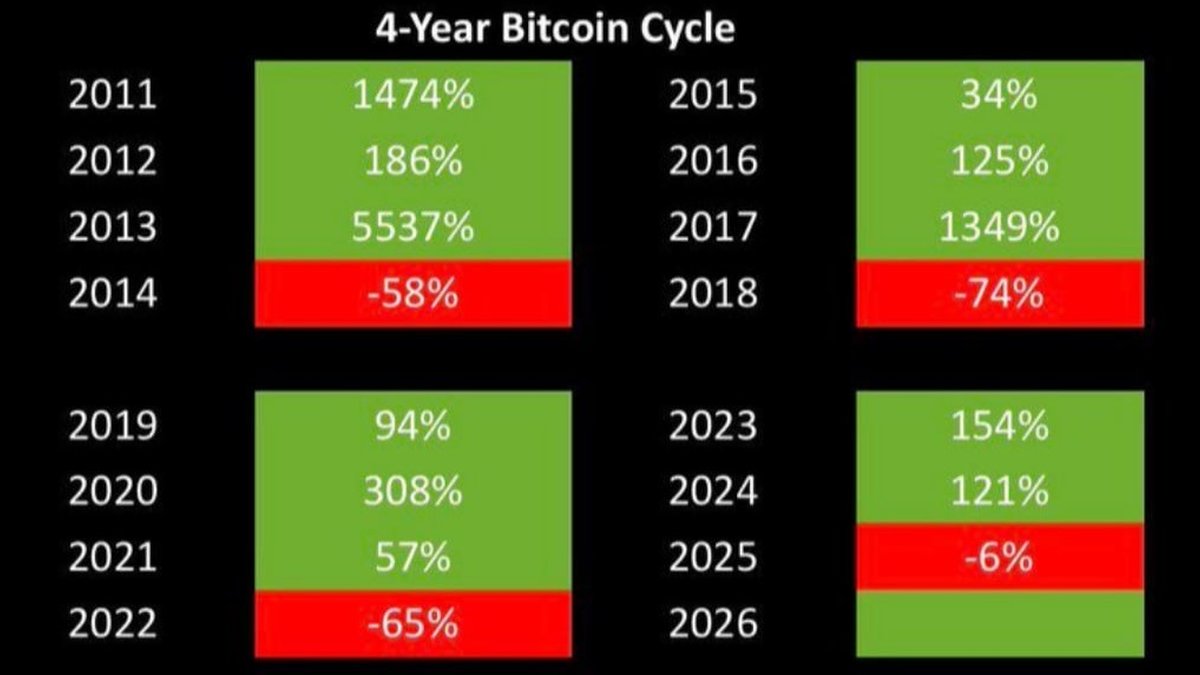

Can oil fall even when a geopolitical oil headline is bullish?

Yes. Markets can price an “unlock” narrative (greater future supply access) at the same time they price higher uncertainty via gold or Bitcoin. Different assets can express different layers of the same event.

Why would China be affected by Venezuela developments?

Because oil access is a strategic input, and Venezuela has historically been linked to global buyers and financiers. If control over export flows or infrastructure direction shifts, bargaining power and access expectations can shift too.

What’s the most practical way to follow this story as an investor?

Focus on tradeable signals: refinery margins and differentials, shipping flows, policy permissions, and cross-asset hedging behavior—rather than relying only on headline intensity.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, investment, legal, or tax advice. Geopolitical situations are complex and can evolve quickly. Market moves may reflect liquidity and positioning as much as fundamentals. Always verify information using primary sources and consider your own risk tolerance.