Crypto Mining at Zaporizhzhia? When Nuclear Power, Peace Talks and Bitcoin Collide

Few places on Earth concentrate as much strategic sensitivity into a single facility as the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. It sits on Ukrainian territory, has been under Russian control since 2022, and remains central to discussions about electricity supply, safety, and any long-term peace arrangement in the region.

In that already complex context, another layer has reportedly appeared at the negotiating table: using a portion of the plant's electricity to mine crypto assets. Depending on whose proposal you read, the plan could involve a joint Russian–United States management arrangement that sidelines Ukraine, a three-party framework with shared ownership, or a 50/50 partnership between Ukraine and the U.S., where part of the output is reserved for industrial or household use and the remainder can be channelled into energy-intensive data centres, including mining.

It is far from clear whether any of these schemes will ever leave the realm of theory. But the very fact that crypto mining is being mentioned alongside ceasefire lines and control of a nuclear facility tells us something important: digital assets have moved into the core of energy and security debates. This article does not take a political position or endorse any specific settlement. Instead, it examines why mining appears in these discussions, what it reveals about the maturing role of Bitcoin, and which risks such a project would carry.

1. Zaporizhzhia as an economic bargaining chip

Long before anyone spoke about blockchains, Zaporizhzhia was an economic anchor. As the largest nuclear power plant in Europe, it supplied a significant share of southern Ukraine's electricity. Whoever controlled it effectively held a lever over regional power prices, industrial output and grid stability.

During active conflict, this control functions as strategic leverage. In a peace framework, however, the logic gradually shifts. The central question becomes: how do you turn a high-risk, capital-intensive asset into something that creates shared benefit rather than permanent tension?

That is where ideas like crypto mining enter the picture. In principle, directing part of the plant's output into mining farms could:

- Generate hard-currency revenues without immediately depending on long-distance transmission lines that may need years of investment to repair.

- Provide a transparent revenue stream that can be divided between parties as part of a settlement or compensation package.

- Allow the plant to operate at stable output levels even if local demand remains depressed, because data centres can be located flexibly and ramped up or down over time.

Those arguments are attractive on paper, especially to negotiators looking for financial mechanisms that do not rely solely on taxes, grants or traditional debt. But they also push Bitcoin and crypto mining into a context where technical feasibility is only one small part of the story. Geopolitics, nuclear safety and public perception become at least as important.

2. Why miners like nuclear power in the first place

To see why anyone would propose mining at a nuclear site, it is useful to review the basic economics of mining. Mining networks convert electricity and hardware into cryptographic security. Operators are constantly searching for three things:

- Long-term access to reliable baseload power.

- Predictable, low-cost electricity that does not fluctuate wildly with weather or fuel prices.

- Locations where industrial deployments can operate for years without frequent shutdowns.

Nuclear generation, when managed safely, ticks many of those boxes:

- It provides continuous generation, unlike wind or solar, which are intermittent.

- Once the plant is built, the marginal cost per megawatt-hour is relatively low and stable.

- The plant can continue producing power even when local demand is temporarily weak, leaving room for alternative loads such as data centres.

For that reason, several countries have already experimented with pairing nuclear or other baseload plants with mining facilities. In a peaceful, regulated environment, the main questions tend to be commercial: price, contract length, risk sharing and grid impact.

Zaporizhzhia is different because the nuclear site itself is contested, and because control over its output is part of a broader negotiation about sovereignty and security. Any mining proposal must therefore be evaluated not just as an energy project, but as an element of a delicate peace architecture.

3. Governance blueprints: two reactors, many vetoes

The governance structure around any such project matters more than the technical design. Different sketches mentioned in public discussion illustrate very different political messages:

• Russia–U.S. joint control: Moscow and Washington co-manage the plant and share revenue from electricity sales and mining, while Ukraine is not a direct party. Economically, this may look efficient; politically, it risks being seen as sidelining the country on whose territory the facility stands.

• Three-party arrangement: Russia, Ukraine and the U.S. each hold a stake in ownership and decision-making, with some formula for allocating power and income. This looks more inclusive but multiplies veto points and may be harder to implement in practice.

• Ukraine–U.S. partnership: Ukraine receives, for example, half of the electricity for domestic use, and the U.S. determines how the remainder is monetised, potentially including sales to mining ventures that could involve Russian interests indirectly.

Under any of these models, key questions arise:

• Legitimacy: Will local citizens, and the broader international community, accept a structure that does not clearly place Ukraine at the centre of decisions about an asset on its own soil?

• Accountability: Who is ultimately responsible if something goes wrong, whether that is a financial loss, a safety incident, or a failure to maintain the plant to agreed standards?

• Transparency: How will mining revenues be measured, audited and distributed? Digital assets are technically traceable, but only if institutions commit to robust reporting.

• Safety integration: Can high-density data centres be installed without interfering with nuclear safety protocols, physical security and emergency planning?

These are not questions that the crypto industry can answer alone. They require input from nuclear regulators, grid operators, local communities and diplomats. Still, anyone active in Bitcoin should appreciate that where and how hashrate is produced is increasingly tied to geopolitical decisions, not just to electricity prices.

4. Monetising a nuclear plant: efficient or tone-deaf?

Using nuclear power for industrial processes is not unusual. What is new here is the idea of placing mining at the centre of a settlement around a disputed facility. That raises at least three ethical and practical concerns.

4.1 Symbolism and public trust

Nuclear plants are not ordinary factories. They sit at the intersection of national identity, fears about safety, and memories of past accidents. For communities living nearby, the plant is often associated with both employment and anxiety.

In that context, announcing that a portion of the output will be directed to mining may be perceived as prioritising distant investors over local needs, unless the design clearly channels benefits back into reconstruction, public services and long-term development. The narrative matters: is the plant being repurposed to rebuild the region, or mainly to serve external interests?

4.2 Allocation of scarce political capital

Post-conflict environments face overwhelming lists of urgent tasks: restoring housing, healthcare, manufacturing, logistics and governance. Designing and implementing a sophisticated mining joint venture consumes scarce legal and diplomatic bandwidth.

The question is not whether mining is inherently good or bad, but whether it should sit near the top of the priority list. In the best case, it could provide an additional revenue stream that supports reconstruction. In the worst case, it could become a distraction that complicates negotiations without delivering commensurate benefits.

4.3 Precedent for future disputes

If the international community accepts a model in which a contested nuclear facility becomes a digital-asset production site under complex shared ownership, that precedent may influence how other disputes are approached. Some will see this as creative economic problem-solving; others may worry that it blurs lines between critical infrastructure and financial experimentation.

For Bitcoin, which often presents itself as politically neutral infrastructure, being embedded in highly sensitive bargains can be a double-edged sword. It can demonstrate relevance and resilience, but also increase the risk that network activity becomes entangled in sanctions debates or political disagreements.

5. A dense web of law, sanctions and regulation

Even if all parties were to agree conceptually on a Zaporizhzhia mining plan, implementation would need to navigate a complex legal landscape.

• Sanctions and capital controls: If any side involved in the project is subject to international sanctions, lawyers would need to determine whether revenue sharing is legally permissible and under what reporting obligations. Using crypto does not remove those constraints.

• Financial transparency: Mining rewards are public on-chain, but that does not automatically translate into clear accounting. Mechanisms for converting digital assets into fiat currencies, or for holding them in reserves, must comply with anti-money-laundering rules and other standards.

• Nuclear governance: Any new industrial activity on site, including data centres, would be subject to scrutiny from national and potentially international nuclear regulators. They would examine cooling requirements, physical access, backup power integration and emergency procedures.

• Taxation and ownership: Determining which jurisdiction taxes the revenues, how losses are treated, and how ownership of hardware and digital assets is recognised would be a non-trivial exercise.

For the broader industry, this underscores a wider point: as soon as mining becomes a component of inter-state negotiations, it crosses firmly into the domain of mainstream public policy. The standards applied will be similar to those used for other strategic industries, not to early-stage technology experiments.

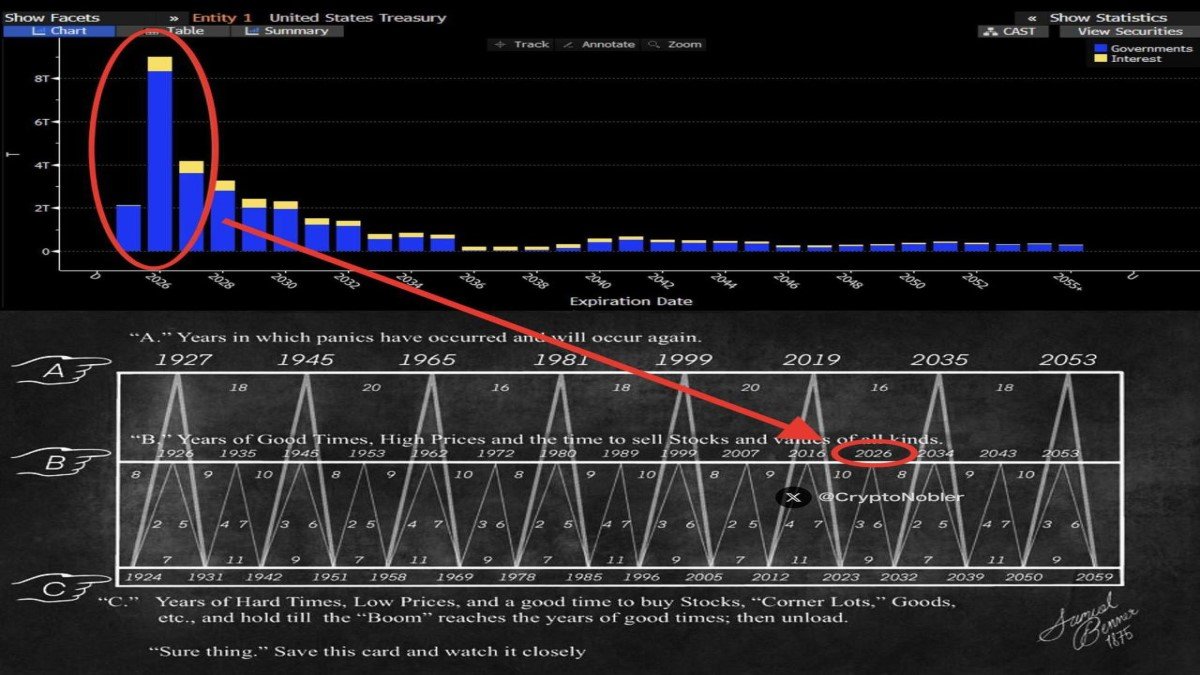

6. What this episode says about Bitcoin's macro evolution

Beyond the immediate headlines, the Zaporizhzhia discussion highlights how much Bitcoin has changed over the past decade. Earlier cycles were often described using internal metrics: halving events, on-chain indicators, adoption curves. Today, analysts increasingly frame Bitcoin as part of a broader macro system, sensitive to:

- Interest rate expectations and central bank policy.

- Fiscal debates and government balance sheets.

- Geopolitical risk, sanctions and energy security.

The idea of attaching mining rights at a nuclear plant to a peace arrangement fits into that trend. It reflects two deeper shifts:

- The financialisation of energy, where every megawatt-hour is treated as a potential financial instrument, whether via traditional markets or new digital rails.

- The institutionalisation of Bitcoin, where mining is no longer seen only as a grassroots activity, but as infrastructure that can be planned at the level of state projects and diplomatic negotiation.

Whether this is positive or not depends on perspective. For some, it signals maturity and staying power. For others, it raises concerns that the original ethos of neutrality and permissionless participation could be overshadowed by state-level interests.

7. Practical lessons for investors and builders

For long-term participants in digital asset markets, there are several grounded takeaways from this debate, even if the specific Zaporizhzhia proposal never materialises.

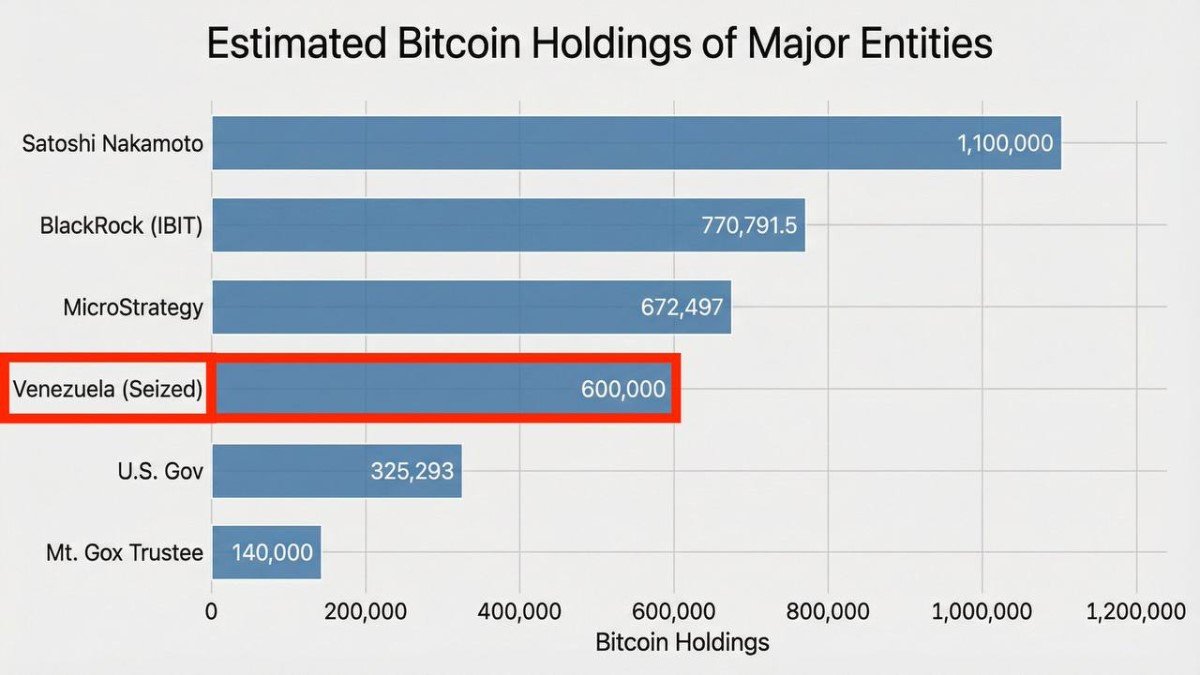

7.1 Where hashrate lives now matters

As networks scale, the geographic and political distribution of hashrate becomes a genuine risk factor. Concentration of mining in regions with contested governance or unclear legal frameworks can increase the probability of sudden policy shifts, forced shutdowns, or reputational questions.

Institutional investors who treat Bitcoin as part of a diversified portfolio increasingly pay attention not only to price and liquidity, but also to the underlying infrastructure: energy sources, environmental footprints and governance arrangements around large industrial deployments.

7.2 Policy risk is no longer an afterthought

Episodes like this demonstrate that policy risk has become structural for digital assets. As soon as mining or holding is discussed in relation to national strategies, it moves out of the realm of purely market-driven activity.

That does not mean digital assets are inherently at risk, but it does mean that long-term theses should consider:

- The direction of regulation in major jurisdictions.

- How governments think about energy transition and grid stability.

- The way sanctions and international law interact with cross-border mining operations.

7.3 Reconstruction and responsibility

Digital assets and decentralized infrastructure can, in the right conditions, support post-conflict reconstruction by attracting capital, improving transparency and enabling new business models. However, projects in such contexts carry a heightened responsibility to be:

- Transparent in how benefits are distributed.

- Inclusive of local stakeholders and communities.

- Resilient to political changes and future disputes.

That is true for mining, tokenization or any other crypto-related initiative that touches sensitive infrastructure.

8. A cautious conclusion

At the time of writing, the idea of using Zaporizhzhia's nuclear output for crypto mining under a multi-party governance model remains just that: an idea. There is no binding agreement, no final technical design, and no guarantee that such a project would pass the many safety, legal and political tests it would face.

Nevertheless, the discussion itself is revealing. It shows that:

- Digital assets have moved into the vocabulary of high-level diplomacy and energy policy.

- Energy infrastructure is increasingly seen through a financial lens, with mining as one of several possible monetisation tools.

- Bitcoin's role in the world is being reinterpreted: not just as a technological curiosity or a macro hedge, but as a network whose security and economics can intersect directly with sensitive, real-world infrastructure.

For participants in the crypto ecosystem, that should be both a sign of progress and a reminder of responsibility. The closer Bitcoin and other networks move to the centre of global systems, the more they will be judged on:

- Transparency in how projects are structured and monitored.

- Safety in how infrastructure choices interact with local communities and the environment.

- Long-term contribution to stability and development, rather than purely short-term revenue.

The Zaporizhzhia mining idea may or may not survive contact with reality. But it already serves one useful purpose: it forces everyone involved in digital assets to ask what kind of role they want these technologies to play in moments of historic transition, and what trade-offs they are willing to accept to get there.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and analytical purposes only. It does not constitute investment, legal or policy advice. Digital assets are volatile and may not be suitable for all investors. Always conduct your own research and consider seeking guidance from qualified professionals before making financial decisions.