The $6.3M Bitcoin Question That Isn’t About Money

There’s a line that sounds cynical until you’ve watched enough markets: capital doesn’t trade morality; it trades consequences. That’s why the latest allegation around the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) and a small Bitcoin sale is more interesting than it looks. Not because $6.3 million in BTC is large—it isn’t. The interesting part is what it would imply about the internal wiring of the U.S. government at the exact moment it’s trying to rebrand Bitcoin from “seized contraband” into “strategic reserve.”

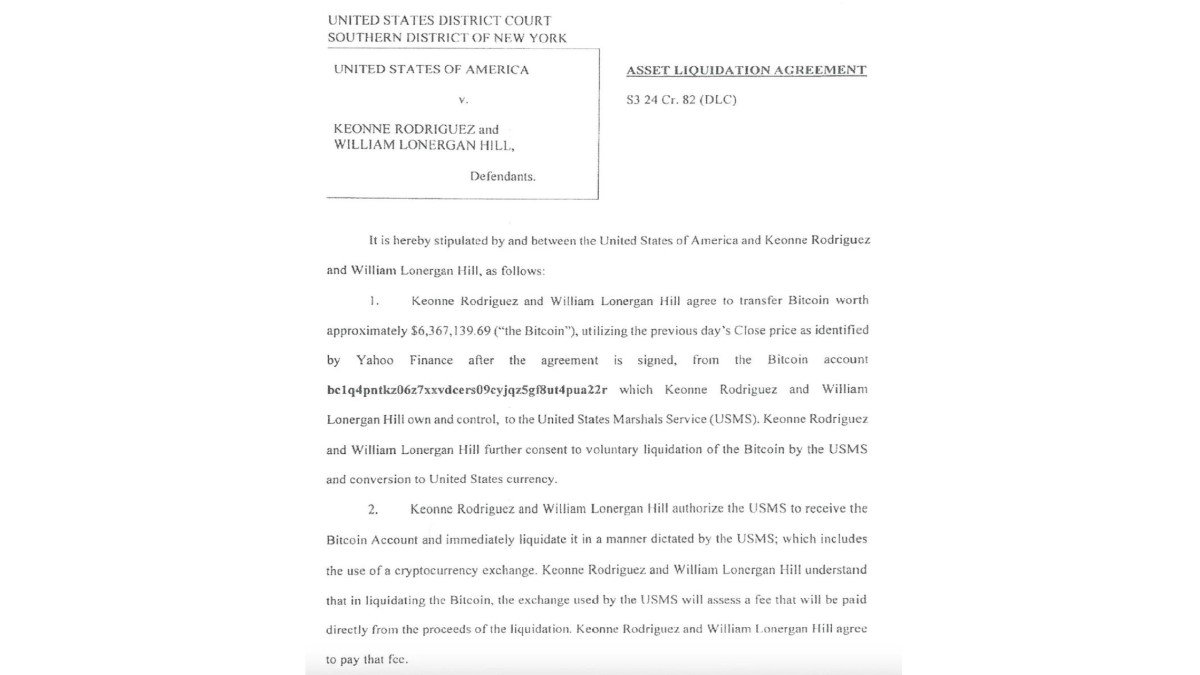

The claim, as it’s circulating, is straightforward: USMS—under the umbrella of the Department of Justice—sold Bitcoin seized in the Samourai Wallet case via Coinbase Prime on Nov 3, 2025. Critics argue this would conflict with President Trump’s Executive Order 14233, which frames government-held Bitcoin as something to be retained rather than routinely liquidated. If you’re looking for a market-moving supply shock, this isn’t it. If you’re looking for a governance stress test, it might be.

Why This Allegation Matters Even If the Amount Is Tiny

In crypto, numbers are loud, but credibility is louder. A $6.3M sale could disappear inside a single hour of global BTC volume. Yet credibility can’t be “averaged out” the same way liquidity can. If a government publicly declares a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve while its operational agencies continue selling by default, markets learn something uncomfortable: policy signals are negotiable, and the machinery underneath them is slow to change.

This is where the story stops being about Bitcoin and becomes about institutional behavior. Executive branches don’t function as one unified organism; they function as a collection of teams, mandates, workflows, and legacy procedures. When a new directive arrives, the big question is not “Is it true?” but “Has it been operationalized?” A reserve policy that doesn’t reach the day-to-day liquidation pipeline is a press release, not a regime shift.

Key takeaway: the market impact of a small liquidation is trivial; the reputational impact of a “reserve policy” that leaks is not.

What Executive Order 14233 Is Trying to Change

The idea behind a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve is conceptually simple: treat Bitcoin more like a long-term sovereign asset than a disposable byproduct of law enforcement. That’s a philosophical pivot. For years, the government’s implicit stance has been “seize, custody, liquidate.” The reserve concept flips the default to “seize, custody, retain.” That shift doesn’t just affect Bitcoin—it affects how investors interpret U.S. policy intent.

But the difference between intent and implementation is the entire game. Asset forfeiture is not a single lever; it’s a system. It touches courts, prosecutors, custody providers, and the financial plumbing that turns seized property into proceeds. If an executive order says “do not sell,” the next practical question is: do the forms, checklists, and standard operating procedures say the same thing?

To keep this brand-safe and educational, here’s the non-sensational framing: executive orders are strong signals, but they are not magic spells. They compete with existing statutory obligations, court orders, victim restitution claims, and agency-level processes that were built for a world where liquidation was the norm.

The Uncomfortable Plumbing: How Seized Crypto Actually Gets Sold

Most people imagine forfeiture as a straight line: law enforcement seizes an asset, then sells it, then money goes somewhere. In reality, it’s a multi-step pipeline with different owners at different stages. Some assets are held pending trial. Some are forfeited after conviction. Some are retained for restitution. Some are sold quickly to reduce volatility risk. Each branch has its own incentives and its own “default settings.”

That’s why the allegation—“Bitcoin was transferred to Coinbase Prime and the receiving wallet now shows zero”—doesn’t automatically prove a sale. A transfer to a prime broker can mean custody, conversion, liquidation, or internal reshuffling. In institutional finance, a wallet hitting zero can simply indicate that assets moved again, not that they were sold. This is exactly why evidence quality matters more than narrative quality.

Educational lens: on-chain observations are powerful, but without confirmed wallet attribution and process documentation, they’re not verdicts. They’re leads.

Three Plausible Explanations (Only One Is a Scandal)

When a story involves government agencies, the safest analytical stance is to consider that boring explanations are often the correct ones. If the allegation is accurate, that’s significant—but there are at least three plausible interpretations that fit the same surface-level data.

1) Routine liquidation inertia: The sale happened because “that’s what the pipeline does,” and the executive order wasn’t yet translated into operational rules for that specific case flow. This would be a governance failure, but not necessarily malicious.

2) Court- or statute-driven exception: The order’s principle is retention, but there may be legally mandated reasons to convert assets—victim restitution, evidentiary constraints, or specific forfeiture terms. If a judge orders liquidation, an agency may comply even if the political messaging prefers retention.

3) No sale at all: The assets were moved into a custody or trading account for safekeeping, accounting, or consolidation, and later transferred elsewhere. A “zero balance” endpoint could reflect operational movement rather than market selling.

Only the first explanation creates the headline conflict: a policy that says “retain” versus a machine that still “sells.” The second and third are far less dramatic—but drama is not the same thing as truth.

The Bigger Conflict: A Reserve Policy vs. the Forfeiture Business Model

This is the part most news coverage misses because it’s not click-friendly: asset forfeiture has an economic logic. Liquidations generate proceeds, and proceeds feed programs, funds, and budgets. Even if every actor is acting in good faith, a retention policy can quietly collide with the incentives of a liquidation-based system.

In other words, a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve is not merely a new attitude toward Bitcoin. It’s a change to cashflow. If agencies historically expected forfeited assets to become spendable proceeds, then “hold the Bitcoin” is not neutral—it removes a funding pathway. That doesn’t mean anyone is corrupt. It means the system has momentum, and momentum resists pivots.

This is why the story is not “Did they sell $6.3M?” The story is “Can a presidential directive reprogram a complex pipeline quickly enough to be credible?”

Market Implications: The Signal Is Stronger Than the Flow

Let’s be clear: a $6.3M BTC sale, if it happened, is not a bearish catalyst on its own. It’s a rounding error relative to Bitcoin’s liquidity. But markets don’t just price supply; they price rules. If investors believe the U.S. is serious about retaining seized Bitcoin, that supports a narrative of structural demand and reduced future sell-pressure from government auctions.

If investors instead learn that retention is aspirational while liquidation continues in practice, the narrative weakens. Not because supply increases, but because trust in policy coherence decreases. Policy coherence matters a lot in 2026, when institutions are increasingly using regulated wrappers—ETFs, prime brokerage, and custodians—to interact with crypto. Institutions don’t need perfect policies; they need predictable ones.

Practical conclusion: the real variable isn’t whether the government sold a small amount; it’s whether the government can demonstrate consistent custody and disposition rules across agencies.

What to Watch Next (If You Want the Truth, Not the Drama)

There are clean ways this story resolves, and messy ways it lingers. If you’re trying to stay analytical, focus less on social-media certainty and more on verifiable checkpoints that either confirm the sale or reframe it.

Look for:

• Agency clarification: A statement explaining whether the transfer was custody-only or liquidation, and under what authority.

• Document authenticity: Confirmation that the “Asset Liquidation Agreement” is real, current, and tied to the specific case.

• Chain-of-custody transparency: Wallet attribution, transaction trace, and whether proceeds (if any) went to a designated government account.

• Policy updates: New operational guidance that explicitly aligns USMS processes with the reserve directive—this is the strongest signal that the government learned and adjusted.

• Congressional or inspector oversight: If the issue is real, oversight tends to appear—not instantly, but eventually.

Conclusion: The Reserve Is a Story Until It Becomes a System

The Strategic Bitcoin Reserve is not just a policy; it’s a test of whether the U.S. government can treat Bitcoin as an asset with strategic time horizons rather than a volatile item to be converted into dollars at the first administrative opportunity. That test doesn’t happen in speeches. It happens in procurement, custody contracts, court directives, and the slow, unglamorous machinery of asset forfeiture.

If the alleged sale occurred in defiance of the intended policy direction, it would be less of a “Bitcoin dump” story and more of a “policy-to-operations gap” story. And if it turns out no sale occurred, the episode still matters: it highlights how easy it is for narrative to outrun verification in a market that lives online.

Either way, the next chapter isn’t about price. It’s about proof—proof of custody, proof of authority, and proof that “Strategic Bitcoin Reserve” is more than branding.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does this mean the U.S. government is secretly dumping Bitcoin?

Not necessarily. Even if a small sale happened, the size is too small to imply a broad liquidation program. The more important question is whether the government’s disposition process is aligned with its reserve messaging.

If an executive order says ‘don’t sell,’ can agencies still sell?

Sometimes. Executive orders guide executive agencies, but they operate alongside court orders, statutory obligations, and specific case circumstances. The key is whether an exception applies—and whether the agency can document that clearly.

Why would the government move BTC to Coinbase Prime?

Because prime brokers can provide institutional-grade custody and execution services. A transfer to a prime platform can be for custody, accounting, consolidation, or liquidation—so the transfer alone doesn’t prove a sale.

What’s the market takeaway for long-term investors?

This isn’t about trading a headline. It’s about tracking whether U.S. policy becomes operationally consistent. Over time, consistency matters more than any one transaction because it shapes institutional confidence and regulatory predictability.