When a Crypto Crime Sentence Shrinks: What the Bitfinex Hacker’s Early Release Really Signals

Some stories land with a built-in moral punch. A major crypto theft, years of investigation, a courtroom conclusion—and then, surprisingly, an early release. It can feel like the plot has been rewritten mid-season, especially when the underlying numbers are so large that they stop feeling like numbers at all.

But if you zoom out, the more interesting question is not “How did this happen?” It’s “What kind of system produces this outcome—predictably?” Because in the U.S. federal system, early release is often less like a lever pulled for one person and more like a set of gears turning the same way for thousands.

What actually happened, in plain terms

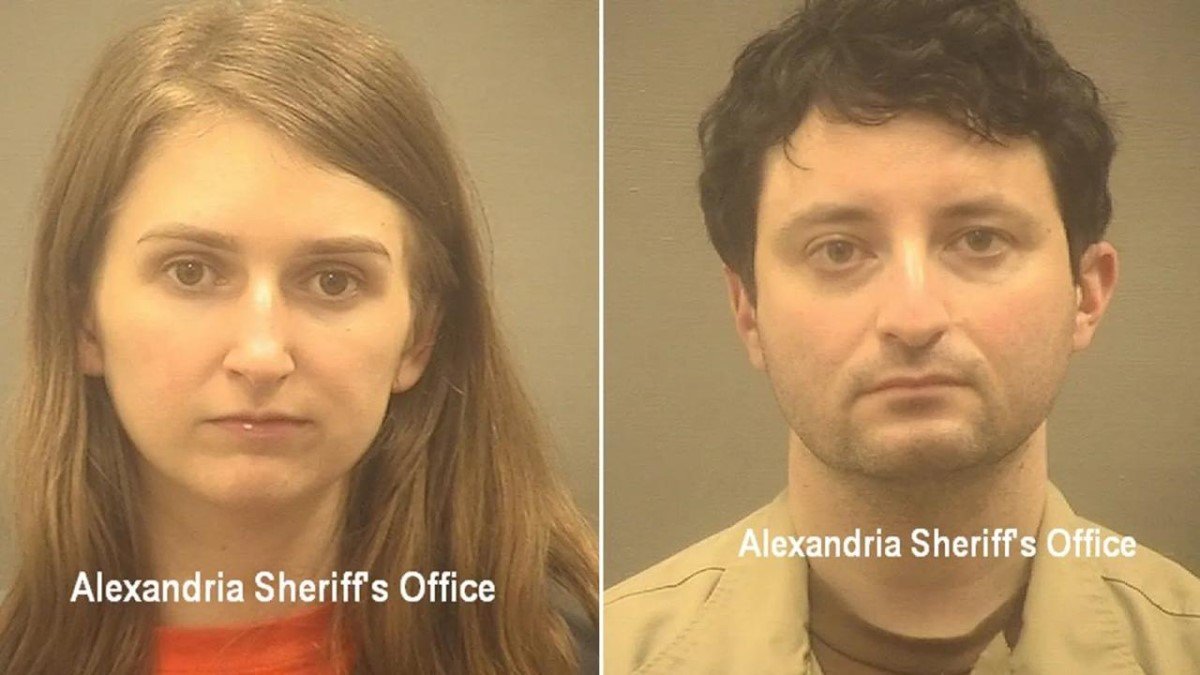

Ilya Lichtenstein was sentenced to 60 months for his role in a money-laundering conspiracy tied to the 2016 Bitfinex incident. According to U.S. prosecutors, the theft involved roughly 120,000 BTC, including 119,754 BTC moved via more than 2,000 transactions from Bitfinex into a wallet he controlled, followed by layered laundering steps. He and Heather Morgan pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering in 2023.

In early 2026, Lichtenstein was released from prison earlier than many people expected, reportedly moving into home confinement under Bureau of Prisons procedures. That distinction matters: home confinement is still custody, just custody with a different address—and different constraints.

Key detail: this was described as a First Step Act outcome, not a pardon, not a personal exemption, and not a reversal of the conviction. His sentence still exists; its shape changed.

Why “early release” is not the same as “getting away with it”

We tend to treat prison time like the entire story because it’s the part we can visualize. A sentence is counted in years; it feels concrete. Yet in many white-collar and cyber cases, prison is only one layer of the consequence stack—and not always the most financially meaningful one.

Even when someone leaves a facility earlier, several weighty realities typically remain: supervised release, strict monitoring, limitations on travel and employment, and the long tail of forfeiture and restitution processes. In cases involving traceable financial flows, the punishment can be quietly extended by recovery efforts and financial friction long after the courtroom cameras are gone.

Think of it like this: incarceration is the loud consequence. Forfeiture and compliance constraints are the quiet consequences. The first shocks the public; the second changes a life.

How the First Step Act can produce an outcome like this

The First Step Act is often summarized as “prison reform,” but operationally it behaves more like a credit-and-eligibility system. It expands ways for some federal inmates to reduce time in secure custody through behavior and program participation—subject to statutory rules, risk scoring, and offense-based exclusions.

Two buckets are easy to confuse: Good Conduct Time (good behavior credit) and Earned Time Credits (credits for program participation). When people hear “First Step Act,” they often lump everything together; in practice, these mechanisms have different pipes and valves.

Good Conduct Time (GCT): after the Act, eligible inmates may earn up to 54 days per year of the sentence imposed (not just time actually served). That shift sounds technical, but technical is where release dates are made.

Earned Time Credits (ETC): for many eligible inmates, participating in certain programs can generate credits—commonly described as 10 days per 30 days of successful participation, with the possibility of an additional 5 days for those assessed as minimum/low risk over consecutive assessments. These credits are designed to move people into prerelease custody (like home confinement) or into supervised release sooner, depending on the case and eligibility.

Separately, Bureau of Prisons policies and directives govern how credits are applied in practice—often emphasizing that when statutory conditions are met, credits must be applied toward prerelease options such as home confinement rather than being trapped behind administrative bottlenecks.

Why this feels “unfair” to the public—and why the system still does it

It’s emotionally intuitive to think: “A bigger crime should always mean more time served.” Yet modern criminal justice reform has been moving toward a different principle: risk and rehabilitation capacity should influence how time is served, not only the headline severity of the offense.

That creates an unavoidable optics problem. High-profile offenders can sometimes qualify for the same machinery designed for broad population outcomes. When the subject is famous (or infamous), the policy becomes a mirror—and the public suddenly notices the rulebook that has been quietly running in the background.

The uncomfortable takeaway: if early release is largely procedural, then outrage is often a referendum on the procedure itself—not the individual outcome.

In crypto enforcement, the deterrence center of gravity is shifting

The Bitfinex case is also a reminder that crypto-era deterrence doesn’t look exactly like the pre-crypto era. Traditional finance enforcement leaned heavily on gatekeepers: banks, payment networks, and regulated brokerages. Crypto introduced new pathways—but it also created an unexpected enforcement advantage: permanent ledgers that can be analyzed years later with improving tools.

In other words, time can work against offenders. The longer assets sit, the more forensic methods improve, the more exchange compliance tightens, and the more likely old flows become legible. This is one reason many investigators emphasize recovery and attribution: if stolen funds can be traced, frozen, and seized, then the economic upside that motivated the crime collapses.

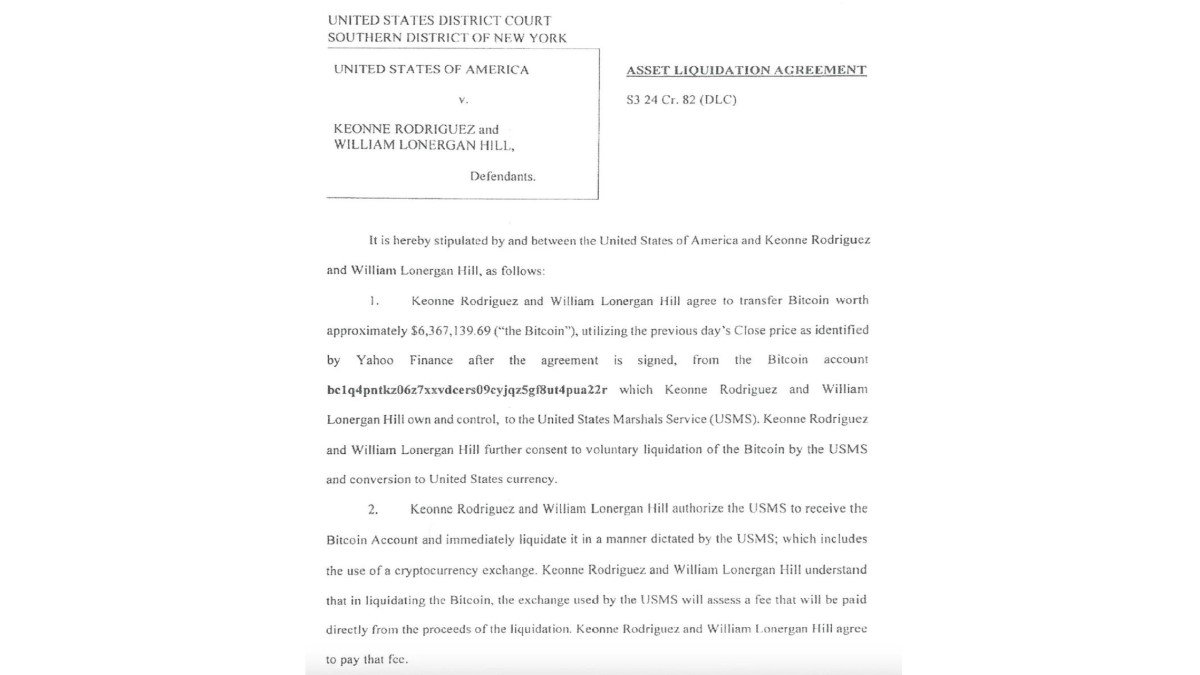

Reuters previously reported that U.S. authorities seized billions tied to the Bitfinex case, illustrating why crypto criminals often face a modern form of consequence: the shrinking probability of successfully enjoying proceeds over time.

What the market should learn from this headline

It’s tempting to read early release as “the system is going soft.” A better interpretation is that the system is changing the unit of punishment. In a world where financial rails are increasingly regulated, the durable penalty can be the inability to move funds, access platforms, or operate inside compliant infrastructure.

For exchanges, stablecoin issuers, and institutional on-ramps, this is also a preview of what regulators will keep pushing: more reporting, better monitoring, and more robust “where did the funds come from?” logic. The goal is not drama; it’s to make illicit pathways expensive and fragile.

Three practical implications:

1) Compliance is becoming the real perimeter. The more regulated the on/off-ramps become, the less “escape velocity” stolen assets have—even if they move quickly on-chain.

2) Sentences will be debated, but recovery is the bigger story. If assets are seized and forfeited, the crime’s payoff can be neutralized regardless of how the custody portion is served.

3) The industry’s credibility depends on boring controls. The future of adoption is not built on spectacle. It’s built on audits, monitoring, clear standards, and predictable enforcement.

What to watch next (without turning it into a price story)

This isn’t a trading signal. It’s a policy-and-structure signal. The next chapters worth watching are not about charts; they’re about how institutions implement rules and how offenders navigate post-sentence constraints.

Specifically, watch for how forfeiture proceedings evolve, how compliance practices harden around mixers and layered laundering patterns, and how “prerelease custody” gets interpreted as agencies refine risk frameworks. These are the slow changes that quietly reshape what is possible in crypto markets.

Conclusion

The headline—“Bitfinex hacker released early”—is attention-grabbing because it compresses a complex system into one emotional moment. But the deeper lesson is more structural: modern justice and modern finance are both moving toward rule-based machinery. That machinery sometimes produces outcomes that feel counterintuitive.

If crypto is maturing, it will look less like a Wild West morality play and more like a world where incentives are engineered: prison credits, compliance credits, risk scoring, custody tiers, and financial rails that reward transparency. Early release is not a celebration. It’s a reminder that the future is being built out of procedures.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does early release mean he was pardoned?

No. The reporting frames it as a procedural outcome tied to the First Step Act framework and Bureau of Prisons policies—more like a reclassification of where the sentence is served (e.g., home confinement) than a cancellation of the conviction.

What does “home confinement” usually involve?

Home confinement is still a form of custody. Conditions commonly include location monitoring, restricted travel, structured check-ins, and tight compliance requirements. It is materially different from being “fully free.”

How do First Step Act credits work in general?

Mechanisms include Good Conduct Time (behavior-based credit) and Earned Time Credits (program-based credit). Statutes and regulations describe credit amounts and eligibility, and Bureau of Prisons policies govern application toward prerelease custody or supervised release depending on the case.

Does this weaken deterrence for crypto crime?

Not necessarily. In crypto-era enforcement, deterrence increasingly comes from attribution, seizure, forfeiture, and the tightening of compliant financial rails. For many would-be offenders, the key question is not “How long is the sentence?” but “Can I ever safely use the proceeds?”

Is this proof that crypto is anonymous or uncontrollable?

If anything, the Bitfinex case is commonly cited as an example of the opposite: on-chain footprints can persist, and investigative capabilities can improve over time. Markets are also trending toward stronger compliance at major access points.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal, financial, or investment advice. References to cases and policies are simplified for clarity; consult qualified professionals for guidance on specific situations.