New York Fed’s Quiet Liquidity Summit: What the SRF Meeting Really Signals

For anyone watching markets, the words ‘Fed’ and ‘liquidity’ in the same headline are enough to raise blood pressure. When news broke that New York Fed President John Williams had gathered Wall Street’s biggest dealers to talk about a key lending facility, social media immediately jumped to the worst conclusion: is this 2019 repo panic 2.0, or the early stages of another global financial crisis?

The reality is more nuanced. The meeting is a serious signal that money markets are tighter, but it is not a red flashing ‘system failure’ light. To understand what is going on, you have to look past the drama and focus on how the Fed’s plumbing actually works – and what it means when the central bank starts quietly reminding banks that a seldom-used backstop is open for business.

What actually happened – and what did not

According to the New York Fed, Williams met this week with the central bank’s primary dealers – the large banks that serve as its main trading counterparties – to discuss the Standing Repo Facility (SRF), an overnight lending tool created in 2021. Officials described the session as part of ongoing engagement with counterparties and said the main goal was to review how the facility is operating as short-term funding costs edge higher and reserves in the banking system decline.

Importantly, this was not an unscheduled midnight call during a market meltdown. The conversation took place on the sidelines of the Fed’s regular U.S. Treasury Market Conference in New York, a scheduled event on the calendar. There were no fresh emergency programs announced and no new policy decisions leaked out of the room.

Still, the fact that the Fed felt it necessary to pull dealers into a focused discussion on the SRF is telling. It signals that money-market conditions have tightened enough that the tools sitting at the core of the rate-control framework deserve a real-world check-up, not just a theoretical review in staff memos.

Why the Standing Repo Facility is suddenly in the spotlight

The SRF is not new, but until recently it lived mostly in footnotes and policy papers. Established in mid-2021, it allows eligible banks and dealers to pledge high-quality collateral – U.S. Treasuries, agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities – and borrow cash overnight directly from the Fed at a rate set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Operationally, the New York Fed’s trading desk runs SRF auctions twice a day, with an aggregate daily capacity currently set at up to 500 billion dollars.

In quiet times, usage is near zero and the facility simply acts as a ceiling on overnight funding rates. If repo markets suddenly become strained and private borrowing costs spike, counterparties can turn to the SRF instead. In principle that simple mechanism should cap money-market stress before it snowballs into something more dangerous.

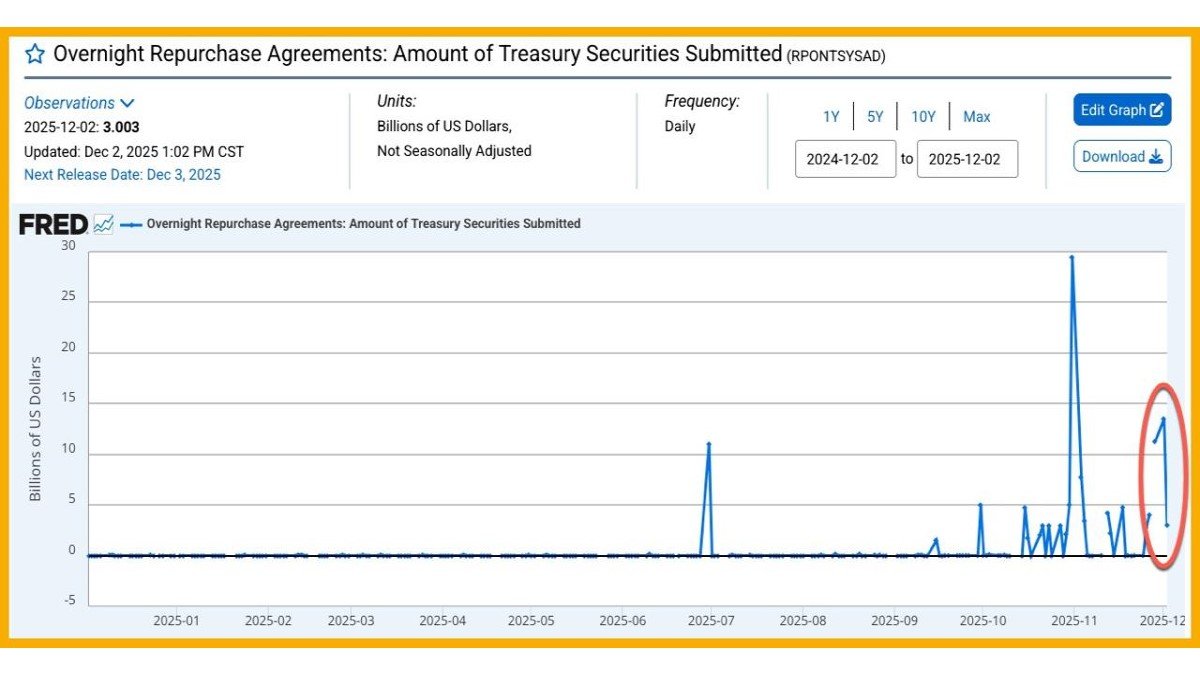

That design has started to be tested. Before the Fed’s late-October policy meeting, several indicators began flashing yellow. Overnight repo rates and the effective federal funds rate drifted toward the top of the target range, and for the first time in a long while, banks tapped the SRF in noticeable size. That is exactly what the facility was built for – capping sudden jumps in funding costs – but the pickup in demand also sent a clear message to policymakers: dollar reserves in the system are no longer super-abundant.

New York Fed officials have tried to get ahead of the narrative. Both Williams and Roberto Perli, the official in charge of daily monetary-policy implementation, have emphasized that the SRF is meant to be used whenever it is economically sensible, not only in emergencies. In recent speeches, they have described active SRF usage as a sign of a healthy backstop, not a sign of crisis, and they have explicitly urged eligible firms to ignore any stigma attached to borrowing from the Fed via this channel.

Alongside that messaging push, the New York Fed updated and republished detailed FAQs on the SRF, walking through how the operations work, who can participate, what collateral is accepted and how the minimum bid rate is set. For a facility that was once obscure, this level of communication is deliberate. The central bank wants banks and dealers to be fully comfortable with the mechanics before stress becomes acute.

QT, T-bills and the slow erosion of ‘ample’ reserves

To understand why this matters now, you have to zoom out from the SRF and look at the broader backdrop: the combination of quantitative tightening (QT), heavy Treasury issuance and evolving cash flows in the dollar system.

Since 2022, the Fed has been shrinking its balance sheet by allowing Treasuries and mortgage bonds to mature without replacement. That QT process has reduced Fed assets from around 9 trillion dollars at the peak of the pandemic response to roughly 6.6 trillion. Every dollar of shrinkage ultimately pulls reserves out of the banking system.

At the same time, the U.S. Treasury has been issuing large volumes of short-term bills to finance deficits, and a drawn-out government shutdown has temporarily swelled the Treasury General Account as spending is delayed. Both dynamics siphon additional reserves away from banks. On top of that, money-market funds have been moving cash out of the Fed’s overnight reverse-repo facility into higher-yielding assets as market rates have risen, which means one buffer of parked liquidity is much smaller than it was a year ago.

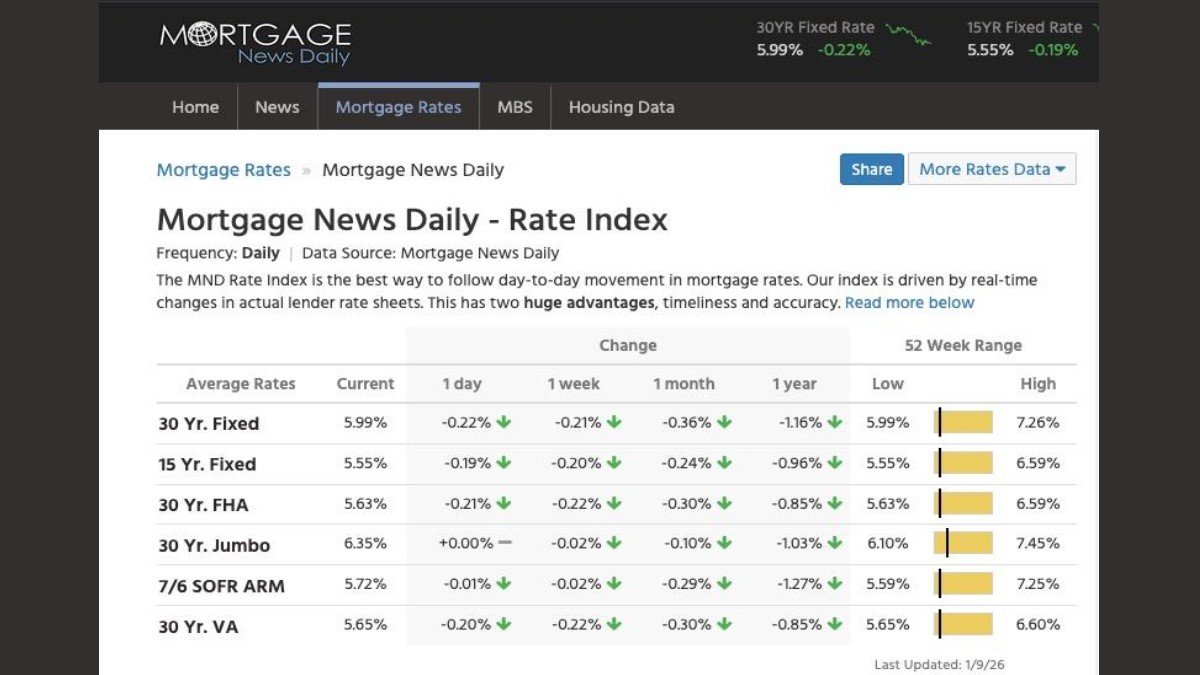

Put all of this together and you get a simple story: on paper, reserves are still described as ‘ample’; in practice, they are getting tighter. Analysts have pointed out that key funding benchmarks such as SOFR and other repo rates have occasionally traded above the interest rate the Fed pays on reserve balances – a classic sign that cash is becoming more scarce and competition for short-term funding is intensifying.

The SRF sits exactly at the junction of these forces. It is supposed to act as a safety valve when QT and other drains push money markets toward the edge. If banks and dealers are willing to tap it freely, it can dampen funding spikes and help keep the effective federal funds rate within the target band. If they hesitate – because of stigma, operational frictions or simple inertia – the system can look much more stressed than it needs to be.

What the New York Fed was really trying to achieve

Seen through that lens, the New York Fed’s decision to convene a focused meeting on the SRF is less mysterious. Officials are juggling three overlapping objectives.

First, they want to maintain control of the policy rate. When the effective federal funds rate trades persistently at the top of the target range, it suggests the central bank is losing some grip on the price of overnight money – the very lever through which it transmits monetary policy to the real economy.

Second, they want to avoid a repeat of September 2019, when a sudden funding squeeze in repo markets forced the Fed to inject emergency liquidity and rapidly expand its balance sheet, catching many participants by surprise. Back then there was no standing facility. Now there is, and policymakers clearly want it to bear more of the load if things get bumpy.

Third, they are trying to choreograph the end of QT. Williams has already signaled that balance-sheet runoff will stop around the start of December, and that over time the Fed will have to resume net bond purchases – not as traditional quantitative easing, but as a technical step to keep reserves from drifting too low as the financial system grows. Communicating that distinction is delicate: ‘we may buy bonds again, but that does not mean we are easing policy.’ In that environment, any sign of tension in money markets becomes politically and financially sensitive.

Bringing primary dealers into the room allows the Fed to stress-test the plumbing from the users’ perspective. Are there operational issues that keep banks from bidding in SRF operations? Are internal risk limits or balance-sheet constraints making it harder to shift funding from private repo markets to the Fed? Are Treasury auctions and collateral markets behaving normally, or are there pockets of dysfunction that do not show up in headline rates? These are the questions that matter much more than the simplistic label of ‘emergency meeting’ that gets thrown around online.

Is this a liquidity crisis, or just a warning shot?

For investors, the key distinction is between a system that is bending and one that is breaking. So far, the evidence points to the former.

On the tightening side of the ledger, the picture is clear. Short-term funding costs have risen, SRF usage has jumped from near-zero levels, and some recent Treasury bill auctions have cleared at relatively elevated yields – all hallmarks of a world where cash is less plentiful than it was. At the same time, the Fed has already responded at the policy level: signaling an end to QT in the near term, leaning into the message that the SRF should be used whenever it is economical to do so, and opening a direct channel with dealers to iron out practical barriers.

On the stability side, there are, for now, no signs of the kind of dysfunction that characterizes a full-blown crisis. Repo markets may be under strain, but they are operating. There have been no credible reports of major institutions failing to roll overnight funding. Credit spreads have widened from their lows, but they do not yet look like markets are pricing systemic failure. All of this suggests that the New York Fed’s meeting should be read as preventive maintenance rather than emergency repair.

That said, the story is far from over. If reserves continue to fall or if funding stress deepens into year-end, the central bank may need to move faster: accelerating the end of QT, tweaking the SRF’s terms to make it even more attractive, or entering a more active ‘maintenance’ phase where it regularly buys Treasuries just to keep reserves from shrinking further. Each of those options would have ripples across bond markets, the dollar and risk assets.

Why this obscure facility matters for risk assets and crypto

At first glance, an overnight repo facility sounds like an obscure plumbing issue far removed from the world of equities or digital assets. In reality, the health of dollar funding markets quietly shapes the backdrop for risk appetite everywhere.

When reserves are abundant and short-term funding is cheap and predictable, leverage is easier to obtain, carry trades proliferate, and volatility tends to be lower. Investors feel more comfortable reaching for yield in everything from high-yield bonds to frontier tokens. When reserves become scarce and overnight rates turn jumpy, the opposite happens: margins are tightened, risk budgets are cut and the cost of rolling speculative positions rises. Even without a banking crisis, a messy money-market environment can amount to a stealth tightening of financial conditions.

The current episode sits in the middle of that spectrum. The Fed is not swinging toward aggressive easing, but it is implicitly acknowledging that there is a limit to how far the system can be drained. By hinting that QT is nearing its endpoint and by normalizing active use of the SRF, policymakers are drawing an invisible line: they will tolerate some stress and some volatility, but not another uncontrolled spike in funding costs.

For crypto markets, the message is mixed. In the short run, sensational headlines about ‘secret liquidity meetings’ and ‘Wall Street panic’ can feed risk-off behavior, especially among traders who remember 2008 more vividly than the subtleties of modern Fed operations. Over a slightly longer horizon, however, an earlier-than-expected end to QT and a shift into a balance-sheet maintenance regime can be supportive for assets that benefit from easier financial conditions and a softer path for real yields. The nuance is that this would not be a classic ‘money printer’ environment; it would be a quieter acceptance that the post-pandemic world requires a permanently larger Fed footprint in money markets.

How a professional investor might read the signal

A more mature way to interpret the New York Fed’s actions is to treat them as a live test of the post-crisis architecture: a system built around the idea of ‘ample reserves,’ standing backstops and a balance sheet that will remain far larger than it was before 2008.

In that framework, a handful of indicators matter more than online narratives. Among the key signposts to watch:

- Where the effective federal funds rate trades relative to the midpoint of the target range.

- How frequently, and in what size, the SRF is used by banks and dealers.

- Whether private repo rates trade persistently above the SRF rate, or whether the facility quickly caps any spikes.

- How smoothly Treasury bill auctions clear, and whether there are signs of strained demand or failed tenders.

- Whether funding stress is broad-based across institutions or concentrated in specific corners of the market.

If those indicators calm down over the coming weeks – particularly after year-end balance-sheet pressures fade – the New York Fed’s dealer huddle will likely be remembered as a technical footnote. If they worsen, investors should be prepared for more explicit interventions: clearer guidance on the minimum level of reserves the Fed is willing to tolerate, faster movement into balance-sheet maintenance purchases, or adjustments to SRF pricing and limits.

The deeper lesson from the New York Fed’s liquidity summit

The most important takeaway from this episode is not that disaster is imminent, but that the Fed is trying to be proactive in managing the side effects of its own policies. After 2008, it built a new architecture for money markets. After 2019, it accepted that this architecture needed a permanent backstop. After the pandemic, it learned that shrinking a massive balance sheet without causing collateral damage is, in Williams’s words, an inexact science.

Now those lessons are being tested in real time. How far can QT go before reserves stop feeling ‘ample’? Will markets treat the SRF as a normal, stigma-free funding option, or will they still see borrowing from the Fed as a sign of distress? And can the central bank manage the optics of restarting bond purchases purely for technical reasons without convincing investors that a full policy pivot is underway?

For a professional news and analysis platform, the value in covering this story lies precisely in separating signal from noise. It is easy to turn a closed-door meeting into a viral doom narrative. It is harder – but far more useful for readers – to connect that meeting to the moving parts of the monetary system and explain what it really implies for rates, liquidity and risk assets.

Right now, the signal is subtle but clear: the New York Fed knows the system is tightening, it wants the plumbing to work as designed, and it is preparing the ground for a steady-state regime in which quiet, technical bond purchases and active use of the SRF are part of the new normal, not signs of panic.

All views in this article are for informational purposes only and should not be interpreted as investment, trading or legal advice.