Between Privacy and Transparency: Why Institutions Need a Middle-Ground Blockchain

In public markets it now feels normal to see banks, asset managers and payment companies talking about blockchains. Stablecoins have moved from niche experiments to major settlement tools, tokenized funds are starting to trade on public networks, and on-chain analytics are used in mainstream research. On paper, the institutional shift toward crypto rails is under way.

Yet when you look closer, a paradox appears. Many of the largest financial institutions are experimenting with distributed ledgers, but the majority of that experimentation happens on private or tightly controlled systems, not on open networks such as Ethereum or Solana. At the same time, regulators are cautiously updating guidance, and boards still ask basic questions about traffic visibility, data protection and legal accountability.

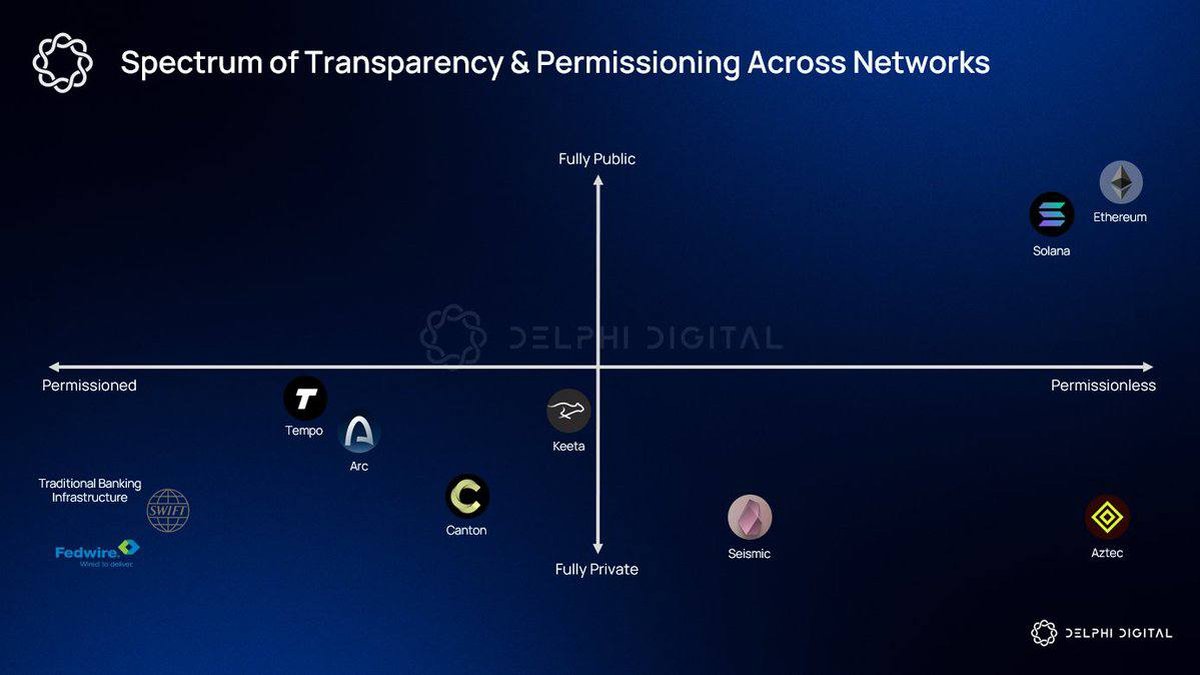

The diagram in the background here – a spectrum of transparency and permissioning – captures the core tension. On one side sit fully public, permissionless chains, where anyone can join and every transaction is visible to the world. On the other side sit traditional banking rails, where only approved entities can participate and almost everything is private. Institutional blockchains have to find a workable position somewhere between these two poles.

1. The Structural Mismatch: How Banks See the World

To understand why this middle ground is necessary, it helps to look at the basic obligations imposed on regulated institutions. Banks, brokers and payment firms operate under three broad constraints that shape how they think about technology.

• Identity requirements. They must know who their clients are, who is sending value and who is receiving it. Legal frameworks around the world require detailed records of customer identity, beneficial ownership and transaction history.

• Client confidentiality. At the same time, they have a duty to protect information about those clients. It would be unacceptable for a competitor to be able to reconstruct a major corporate client’s cash flows or trading strategies simply by watching a public data feed.

• Supervisory oversight. Regulators expect to be able to audit activities, understand exposures and check that institutions are following agreed rules. That often means maintaining clean, machine readable records and being able to provide them on demand.

When you combine these three requirements, a picture emerges: institutions want public accountability over who is allowed to participate, but selective visibility into what those participants are doing. This is almost the mirror image of how most public blockchains operate today.

2. Public Chains: Public Money Flows, Pseudonymous Accounts

Open networks such as Ethereum or Solana are engineered around a very different trade-off. Anyone with an internet connection can generate a key pair and begin transacting. Addresses are pseudonymous strings rather than named accounts, and the ledger is visible in real time to anyone who cares to observe it.

That design brings several powerful advantages. It allows for global access without central gatekeepers, makes censorship harder, and enables independent verification of supply, movement and protocol rules. For individual users, it creates a sense of self-directed control over assets that does not depend on a particular institution staying solvent or cooperative.

But the same properties that make these networks attractive to retail users create headaches for institutions:

- Pseudonymous addressing makes it difficult to map on-chain activity to legally recognized entities without extensive off-chain data and analytics.

- Full transparency of transaction flows means that competitors, counterparties and even outside observers can build detailed pictures of balances, strategies and flows between known addresses once a link to an institution is established.

- Open participation implies that the network cannot easily restrict who can send value through the same settlement layer, which complicates clean separation between regulated business and unrelated activity.

Put simply, the typical public chain is built around the idea of public money flows and private identity. Institutions need almost the opposite: public identity, private money flows. That is the structural mismatch at the heart of the institutional adoption debate.

3. Why “Just Use a Private Chain” Isn’t Enough

One obvious response is to say: if public networks are too transparent, institutions should simply use private or permissioned ledgers. That is exactly what many large banks have tried over the past decade. Projects like Canton, Arc, Tempo and others sit closer to the traditional side of the spectrum: only approved entities can run nodes or submit transactions, and data is carefully partitioned.

These networks solve part of the problem. They allow firms to retain strong control over who participates, where nodes are hosted and how data is replicated. They can embed regulatory requirements into onboarding and transaction flows, and they make it easier to demonstrate compliance to supervisors.

However, purely private chains face two major limitations.

- Limited composability. If each consortium builds its own closed ledger, assets and applications are siloed. It becomes hard to achieve the seamless, global liquidity that gave public networks their original appeal.

- Constrained innovation. Open ecosystems benefit from thousands of independent developers experimenting with new ideas. Closed networks tend to evolve slowly, tied to the priorities and budgets of their founding members.

The result is a fragmented landscape: on one end, vibrant public ecosystems with rich innovation but challenging privacy profiles; on the other, institution-only networks that are compliant and safe but often isolated. The missing piece is a design that can borrow strengths from both sides.

4. Mapping the Spectrum: From Fedwire to Aztec

To visualize the problem, imagine a two dimensional chart. The horizontal axis runs from permissioned on the left to permissionless on the right. The vertical axis runs from fully private at the bottom to fully public at the top.

• Traditional banking rails like Fedwire or SWIFT sit in the bottom left: only licensed institutions can participate, and transaction details are hidden from the broader world.

• Private financial networks such as Canton or Arc cluster nearby: permissioned consortia with carefully managed visibility and strong legal agreements.

• Public smart-contract chains such as Ethereum and Solana occupy the top right: anyone can join, and transaction data is visible to all.

• Privacy-focused public systems like Aztec or other zero-knowledge based projects push downward toward the fully private, permissionless corner: they keep participation open while encrypting most or all transaction details.

From the perspective of regulated institutions, neither extreme is ideal. Purely private, permissioned systems feel safe but risk re-creating the limitations of legacy infrastructure. Fully transparent public ledgers solve global access and composability, but expose clients to forms of visibility they cannot accept. Fully private yet permissionless systems introduce powerful confidentiality but raise fresh questions for supervisors who depend on being able to observe system-wide risk.

The institutional sweet spot therefore lies somewhere in the middle of this chart: networks that are open enough to connect with the broader crypto ecosystem and benefit from its innovation, yet structured enough to meet regulatory and commercial privacy standards.

5. Design Principles for a Middle-Ground Institutional Blockchain

What would a network in that middle region actually look like? There is no single blueprint, but several design principles are emerging from current experiments and policy discussions.

5.1 Public identity, selective disclosure

Institutions can accept that their presence on a network is known – indeed, that may be desirable for trust – but they need granular control over what transaction information is visible to whom. This suggests architectures built around:

- Verified on-chain identities for banks, brokers and large clients, anchored in off-chain legal documentation.

- Encrypted transaction payloads where only relevant parties, and possibly supervisors, can view full details, while the broader network sees minimal metadata.

- Selective disclosure tools based on zero-knowledge proofs or viewing keys, allowing institutions to demonstrate compliance or solvency without exposing every transaction line item.

5.2 Programmable policy controls

Instead of relying solely on manual procedures, the network itself can enforce certain rules. Examples include:

- Address lists that ensure only regulated entities can hold particular classes of tokenized assets.

- Built-in checks for transfer limits, sanctions screening or travel-rule style information sharing, implemented as smart-contract logic.

- Clear mechanisms for emergency interventions that are tightly scoped and transparent, such as freezing a specific asset in response to a court order.

These tools move the conversation from “don’t use crypto rails” to “prove that your crypto rail enforces the same standards as the existing system.”

5.3 Interoperability with public ecosystems

For many institutions, the goal is not to live forever on a fully private ledger, but to have safe corridors between their controlled environment and public liquidity. That implies:

- Bridges that are governed by clear rules, where tokenized deposits, funds or securities can move to public chains under defined conditions.

- Shared technical standards so that a token issued on an institutional network can be recognized and used by wallets, exchanges and applications elsewhere, when appropriate.

- Risk-aware routing, where institutions can decide which counterparties and venues they are willing to connect to, rather than being forced into an all-or-nothing model.

In this vision, the institutional chain becomes a kind of “base camp”: a safe environment where regulated entities settle among themselves, with deliberate, well supervised links to the wider crypto world.

6. Why the Privacy–Transparency Balance Is So Hard

If this middle ground is so attractive, why has it taken so long to emerge? The answer is that getting the balance right between privacy and transparency is technically and institutionally difficult.

From a technical standpoint, tools such as zero-knowledge proofs, confidential transactions and secure enclaves are still maturing. They can hide sensitive data while allowing basic verification, but they also introduce complexity, new attack surfaces and sometimes performance trade-offs. Networks must be fast and reliable enough to handle real-world volumes while preserving confidentiality and auditability.

From an institutional standpoint, there are multiple stakeholders with different concerns.

- Compliance teams want clear assurances that they can meet all reporting requirements, including access to raw data when needed.

- Business units want the flexibility to design new products and interact with broader markets without being locked into one vendor or framework.

- Technology groups need standardization so they can integrate the network into existing infrastructure without rebuilding everything from scratch.

- Regulators want to avoid both systemic opacity and uncontrolled experimentation.

Reaching a consensus architecture that satisfies all of these constraints takes time. That helps explain why we still see parallel experiments across permissioned networks, public chains with compliance layers, and privacy-focused systems, rather than a single dominant institutional solution.

7. What This Means for the Future of Crypto Infrastructure

For the broader digital-asset ecosystem, the institutional search for a middle ground carries several important implications.

First, it suggests that the debate is no longer about whether institutions will use blockchains, but about which type and under what conditions. The old narrative of an explicit battle between traditional finance and crypto is gradually giving way to a more nuanced picture: different layers of the financial system occupying different points along the transparency–permissioning spectrum.

Second, it implies that infrastructure projects able to serve both sides of the spectrum may have an advantage. Networks that can host fully public, permissionless applications while also supporting segregated, privacy-preserving environments for institutions are well positioned to capture diverse flows. Likewise, tooling companies that specialize in compliance, monitoring and secure data sharing can become key enablers.

Third, it highlights the importance of clear, predictable regulation. When supervisors articulate how they expect institutional blockchains to handle identity, data retention and emergency powers, it becomes easier for technology providers to design systems that fit those expectations. The shift from a default of “don’t experiment” to “show us how you will experiment safely” is subtle but powerful.

8. Takeaways for Long-Term Participants

For investors and builders who take a multi-year view, the discussion around privacy, transparency and permissioning is more than an abstract policy debate. It shapes which platforms will attract institutional flows and which applications will sit at the junction between consumer crypto and regulated finance.

• Do not assume institutions will simply adopt existing public chains without modification. While some may use them for specific purposes, many core activities will require additional privacy and control layers.

• Watch for projects that explicitly target the middle of the spectrum. These may include networks that combine permissioned access with modular privacy, or public chains that offer institutional subnets or specialized rollups.

• Expect hybrid architectures. It is increasingly likely that an institution will run a mix of systems: tokenized deposits on a permissioned ledger, hedging instruments on a public derivatives venue, and customer applications that abstract away the underlying complexity.

• Remember that user trust is multi-dimensional. For retail users, self-custody and openness may be paramount. For institutions, legal clarity and data protection often matter just as much as decentralization.

9. Conclusion: The Middle of the Spectrum Is Where the Action Will Be

The story of institutional adoption is not a simple countdown to the day when every major bank moves its entire balance sheet onto a single public chain. Instead, it is a gradual process of experimentation, negotiation and architecture design along the axis of transparency and permissioning.

The core obstacle today is not a lack of interest in crypto, but a clash between how public blockchains handle identity and information, and how regulated institutions are required to handle them. Public networks make value flows radically transparent while leaving account identity pseudonymous. Institutions need the reverse: clear identification of participants combined with protection of their commercial activity.

Bridging that gap requires new types of networks that sit between traditional banking infrastructure and fully open chains. These middle-ground systems will combine verified identities, encrypted transaction data, programmable policy controls and carefully governed links to broader ecosystems.

For participants who understand this spectrum and track how different projects position themselves along it, the coming years should offer no shortage of opportunities. The institutions are not standing still; they are looking for rails that allow them to preserve client confidentiality and regulatory discipline while tapping into the speed, composability and global reach that made crypto compelling in the first place.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment, legal or tax advice. Digital assets are volatile and involve risk. Always conduct your own research and consult a qualified professional before making financial decisions.